Ethnic violence and human rights in Kyrgyzstan

This country spotlight refers to data published in 2019. For the most recent data, go to our Rights Tracker.

Kyrgyzstan’s relatively peaceful presidential election in 2017 gives hope that the nation can make lasting changes. However, the situation of ethnic minorities there has shown little improvement since the outbreak of inter-ethnic violence between the ethnic majority Kyrgyz and the ethnic minority Uzbek population.

UN reports estimate nearly 400,000 people were displaced as a result of the violence ignited by the overthrown former president Kurmanbek Bakiyev. The rampant violence in southern Kyrgyzstan led to the death of 356 people in four days in June 2010. In some cases, villages were decimated and thousands were forced to flee to neighbouring Uzbekistan for refuge.

Human Rights Watch reported that as a result of the June 2010 violence, ‘3,500 criminal cases involving charges of mass disturbance, murder, inflicting bodily harm, arson, destruction of property, robbery, and other crimes committed’ were opened and left for the government to investigate. However, since the events of 2010, the Kyrgyz government continues to deny justice for the victims of the ethnic violence. The 2017 Human Rights Watch World Report notes that the government ‘took no steps to review the torture-tainted convictions delivered in its aftermath.’ The Uzbek population as a whole has not yet received proper redress for the injustices they experienced nor punishment for the perpetrators.

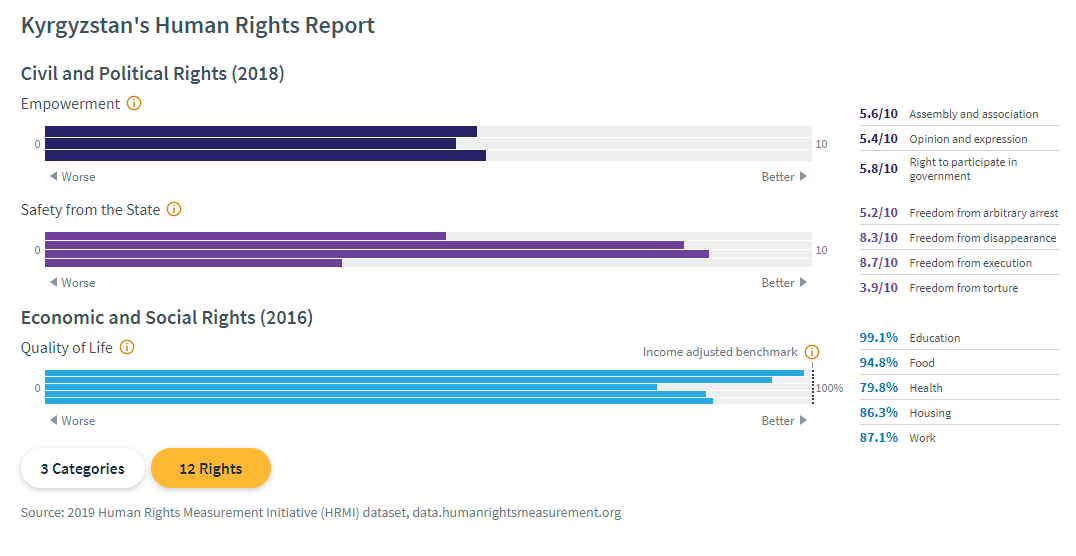

HRMI’s civil and political rights measurements give Kyrgyzstan a score of 3.9/10 for freedom from torture, with ethnic groups identified as being particularly at risk of violations. HRMI also reports that the Uzbek population is one of the more vulnerable groups at risk for torture in Kyrgyzstan.

HRMI also reported scores for Kyrgyzstan of 5.8 out of 10 on the right to participate in government and 5.2 out of 10 for freedom from arbitrary arrest. For each of these scores, ethnic minorities are at particular risk of violations of their human rights.

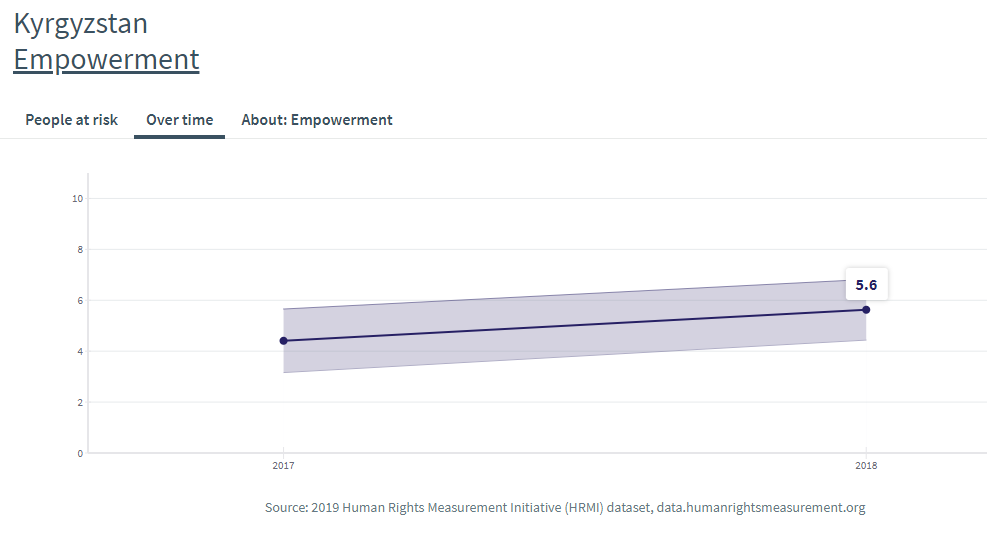

The good news revealed by HRMI’s data is that there has been a small but substantial improvement in empowerment rights in Kyrgyzstan over the last two years, rising from 4.4 to 5.6 out of 10.

Even though the sharp spike in violence against ethnic minorities occurred in 2010, nine years later HRMI’s data reveals that these groups are still in a position of vulnerability and living at risk of human rights violations.

It’s also noteworthy that in economic and social rights, Kyrgyzstan scored well for the right to education, but the other quality of life scores show a substantial gap between what the country ought to be achieving and its current performance.

The Kyrgyzstan/Uzbek ethnic conflict provides a pertinent example as to why HRMI’s work is necessary. The massive human rights violations against the Uzbek people require justice and those responsible for the crimes against the Uzbek population need to be held accountable to the standards provided by international law for their crimes. As Amnesty International’s Kyrgyzstan expert, Maisy Weicherding, said recently, ‘There are wounds that time will not heal. Truth, accountability and justice are the only tools that will mend the bridges between the two ethnic communities.’