Māori, disabled people, children, and people in poverty suffer human rights violations in New Zealand

The 2020 Country Report on New Zealand contains some positive scores, but also some strikingly poor results, particularly in terms of who is most at risk of rights abuses. Of 13 rights measured, New Zealand’s scores only put it in the top ‘good’ category for 3 rights.

Keep reading for more information on these headlines that come from HRMI’s human rights data:

- If New Zealand were to operate at its full potential, 500,000 additional people could experience food security.

- Poverty and inequity behind human rights violations. If New Zealand were operating at its full potential given its current resources, it could lift 280,000 people out of relative poverty.

- Experts highlight threats to the rights of children and young people. If New Zealand were operating at best practice, an additional 11,500 secondary school aged children could be enrolled in secondary school, and an extra thousand children would have a much better chance of reaching their fifth birthday.

- If New Zealand used its resources effectively, an additional 500,000 people could safely manage their sanitation.

- If New Zealand were operating at its full potential given its current resources, 19,000 unemployed individuals could get a job within 12 months and avoid long-term unemployment.

- Māori suffer high levels of human rights violations

- Disabled people suffer wide range of human rights violations

The civil and political rights data, and the people at risk responses, were collected as the Covid-19 pandemic was beginning to sweep the world.

The economic and social rights data are based on figures from international databases and score every year 2007-2017.

How do HRMI’s data work?

HRMI data can help boost efforts to improve people’s lives in New Zealand by giving definitive scores measuring government performance on economic and social rights outcomes. Each rights score can then be used to show where change is needed most and how these changes can be achieved.

So, how does HRMI work? HRMI’s ground-breaking methodology allows us to score countries on how well they use their income for economic and social rights (ESR) outcomes. In particular, our current data focus on the rights to food, health, housing, work, and education. To calculate a country’s ESR scores we use the SERF Index methodology, developed by HRMI co-founder Susan Randolph and her colleagues Sakiko Fukuda-Parr and Terra Lawson-Remer.

The SERF Index combines country achievement and country income to produce a ‘best practice’ benchmark that records the best results that any country has achieved over the last 20 years, at every income level. Each country’s current achievement level is then compared to the best practice outcome for its income level and given an ESR score as a percentage of that result. So any score that’s less than 100% is showing that there’s a gap between how that country is doing, and the best result of any other country with the same level of income.

The ESR scoring methodology takes income into account, so it can assess all countries on a level playing field. It can then be used to reveal how a country can improve its rights performance, and by how much, even without more income or resources.

When a country scores 100% on the performance of a right, it means that the government is keeping its human rights promises to do its very best for its people within the constraints of the country’s resources. All countries can score 100%. Any score below 100% shows that there is realistic room for improvement, even at the country’s current level of resources. An underperforming country can use HRMI’s ESR scores to see which of their nearby countries are doing better and identify policy lessons from them.

There is a lot of cross-over between HRMI’s human rights performance indicators and the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) targets and benchmarks. Countries can use HRMI’s scores to evaluate their own progress and their potential to reach the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, given their current level of income.

HRMI’s benchmarks and assessment standards

HRMI’s methodology uses two benchmarks and two assessment standards when evaluating a country’s ESR performance.

The first benchmark is the ‘income adjusted’ benchmark. Using this benchmark, countries are compared with other countries of a similar income level, allowing us to evaluate how effectively each country is using its available resources. The second benchmark is the ‘global best’ benchmark. This benchmark evaluates country performance relative to the best performing countries at any level of resources.

Both benchmarks are useful for different purposes. The country scores measured against the income adjusted benchmark show how effectively a country is using its resources to achieve good rights outcomes. This also tells us how much its performance can be improved even without extra income. The scores measured against the global best benchmark show how far a country has to go to do as well as any country in the world. These global best scores are important because even if a government is doing its best with their current resources (so it has an income adjusted rights score close to 100%), a country with very low income will likely still have many people not fully enjoying their human rights, which will be reflected in low scores when measured against the global best benchmark.

The assessment standard tells us which collection of rights indicators we use to evaluate the ESR performance of a country. The difference between the two assessment standards is to do with the availability and relevance of data for low and middle income countries versus high income countries.

The low and middle income assessment standard includes rights indicators which low and middle income countries are more likely to have data on, and/or which are more relevant to the rights challenges they currently face. The high income assessment standard includes rights indicators high income countries are most likely to have data on, and/or which are more relevant to the rights challenges they face.

For example, when figuring out how well countries are doing at fulfilling the right to education, for low and middle income countries we look at primary and secondary school enrolment rates. This tells us about access to education. Both indicators are widely available for low and middle income countries and vary widely across them.

But in high income countries, primary school enrolment is essentially universal, so this indicator isn’t a very useful measure of access to education. Instead, for our high income assessment standard we use the secondary school enrolment rate as our single indicator of access, but we also include an indicator of school quality: student performance on the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) tests. School quality is no less a concern for low and middle income countries, but unfortunately, at this time there is no test of student performance that is widely used by low and middle income countries.

We do produce scores on all indicators for all countries if the data are available. So, for example, you can see HRMI scores related to a low income country’s PISA results if that country participates in the PISA assessments.

It can be useful to toggle between the two assessment standards, and check out our scores on the individual indicators, on the country pages of the Rights Tracker.

HRMI’s data are useful for New Zealand’s change-makers

Let’s explore the economic and social rights performance of NZ using HRMI’s ESR data. These data cover the 2007 to 2017 period. The population of NZ in 2017 was 4.8 million, at which time NZ had a GDP per capita of $36, 046 (in 2011 PPP dollars). Given NZ’s high per capita income level, there is likely to be little difference between its scores using the global best benchmark and the income adjusted benchmark. However, to present NZ’s scores in the best possible light, in our assessment we use the income adjusted performance benchmark using the high income assessment standard.

Right to Food

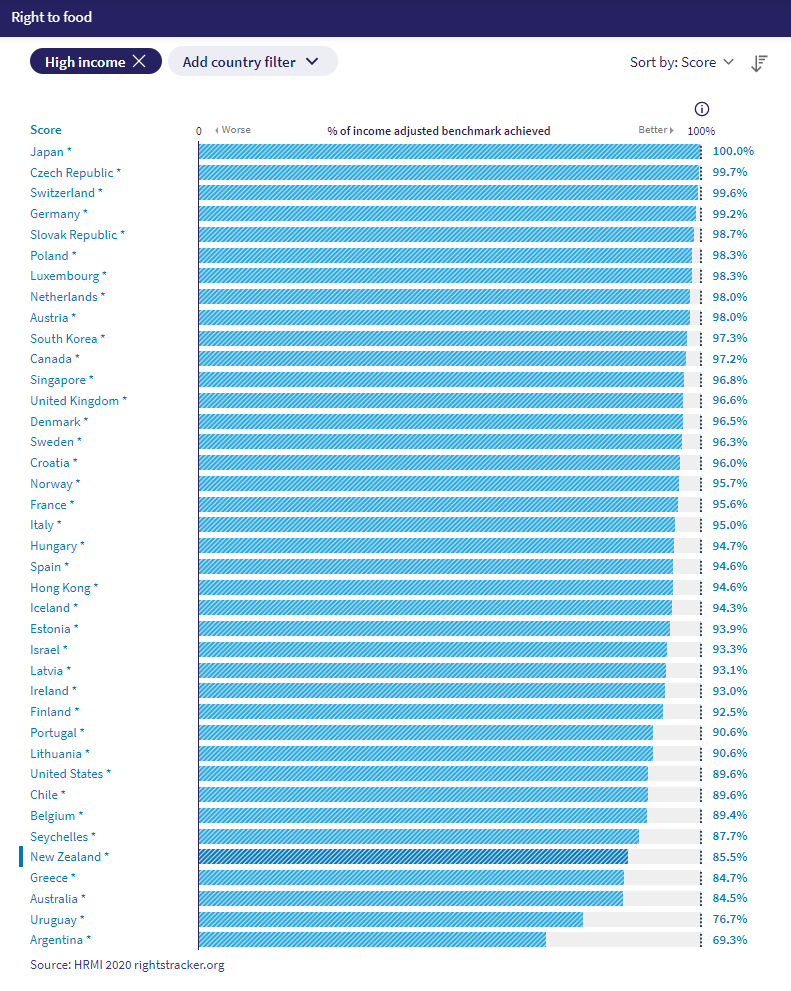

New Zealand scored 85.5% on the right to food, which is based on the percentage of the population that is food secure.

We use food security as a high-level ‘bellwether’ indicator to reveal how many New Zealanders have adequate access to food. (For more on this, please see our Methodology Handbook.)

This score means New Zealand is only doing 85.5% of what should be possible with its current GDP per capita to ensure the enjoyment of the right to food. When combining this score with population statistics, HRMI data tells us that:

If New Zealand were to operate at its full potential, 500,000 additional people could experience food security.

HRMI’s Right Tracker allows us to compare rights scores across countries or groups of countries. As shown below, when comparing right to food scores across high income countries, we can see that New Zealand ranks near the bottom of the list.

This graph tells us that New Zealand policy-makers could look to other high income countries who are doing much better (e.g. Japan, Czech Republic, Switzerland, Germany and many others) for examples of ways to make improvements.

Right to Health

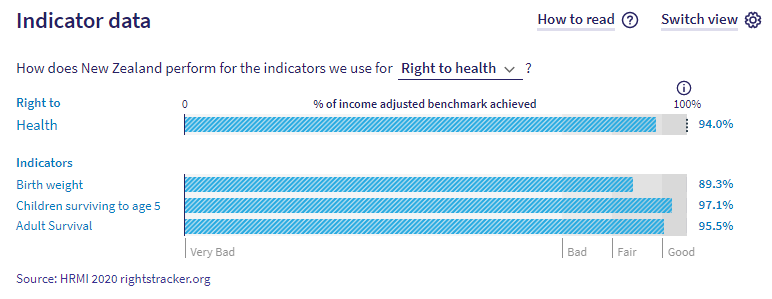

New Zealand scores 94% on the right to health.

As shown in the image below, this score comes from three indicators: the percentage of infants who are not low birth weight (score = 89.3%); children surviving to age five (score = 97.1%); and adult survival (score = 95.5%).

On average, these scores tell us that the extent to which New Zealanders enjoy the right to health is 94% as high as it could be given New Zealand’s current income level.

When we line up all high income OECD countries in order of their right to health HRMI scores, New Zealand is ranked 9th out of 31.

If New Zealand were operating at best practice, an extra thousand children would have a much better chance of reaching their fifth birthday.

Right to Education

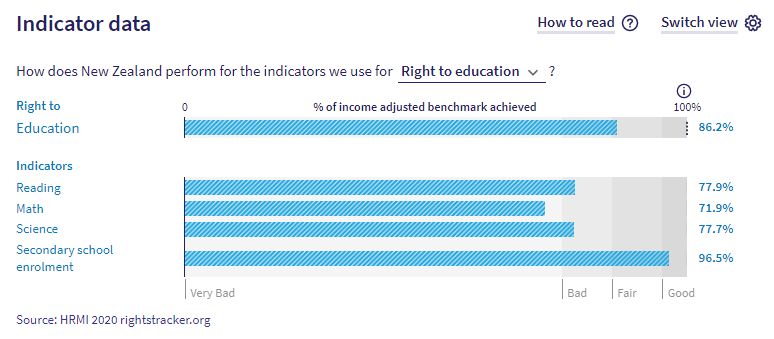

HRMI uses four indicators under the high income assessment standard for the right to education. The first three indicators reflect the percentage of students achieving level 3 or better on math, science and reading PISA tests. The fourth indicator is the net secondary school enrollment rate. HRMI’s overall right to education score is computed by first calculating income adjusted scores for the three PISA tests and then taking the average. This result is then averaged with the country’s secondary education score.

As shown on the Rights Tracker image, New Zealand’s income adjusted scores on the PISA reading, math and science tests are 77.9%, 71.9%, and 77.7%, respectively. The average PISA score is therefore 75.8%. When combining this PISA average with the secondary school enrollment score of 96.5%, New Zealand gets an overall right to education score of 86.2%.

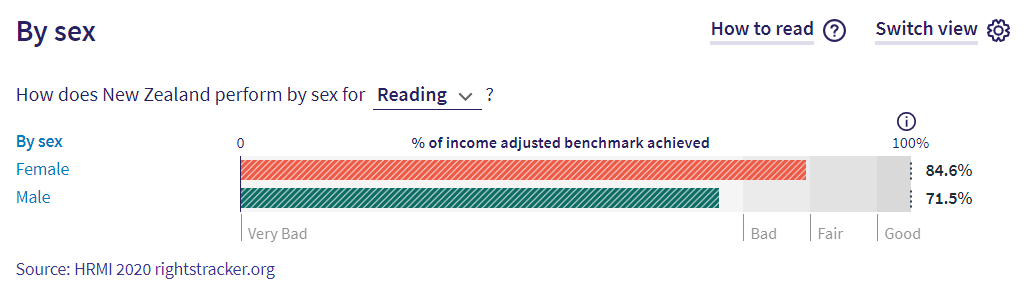

Data are also available for comparing right to education indicator scores between females and males. While all of New Zealand’s PISA scores are considered poor, the screenshot below shows that New Zealand females have better PISA reading scores than New Zealand males (84.6% versus 71.5%). On the other hand, males score better on PISA math tests than females (74% versus 69.7%), and perform slightly better in PISA science tests than females (78.4% versus 77%).

If New Zealand were operating at best practice, an additional 11,500 secondary school aged children could be enrolled in secondary school.

Right to Work

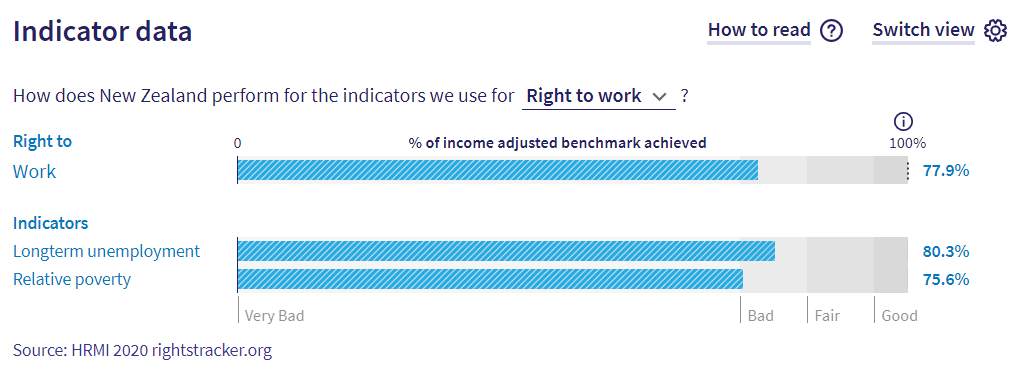

New Zealand’s score for the right to work is 77.9%, which is an average of two indicator scores. These scores mean New Zealand is only achieving 77.9% of what should be possible with its current income to ensure the right to work is enjoyed by all. This is a poor score.

The first indicator is the percentage of the unemployment population who are not long-term unemployed (score = 80.3%). Long-term unemployment refers to the number of people with continuous periods of unemployment extending for 12 months or longer, expressed as a percentage of the total unemployed population. As shown by the grey bars, New Zealand’s performance here is categorised as ‘Bad’, but not terrible.

The second indicator is the percentage of the population that is not in relative poverty (score = 75.6%). Relative poverty is based on the equivalised disposable household income concept and is defined as having an income less than 50% of the median income. This score is also categorised as ‘Bad’.

If New Zealand were operating at its full potential given its current resources, 19,000 unemployed individuals could get a job within 12 months and avoid long-term unemployment.

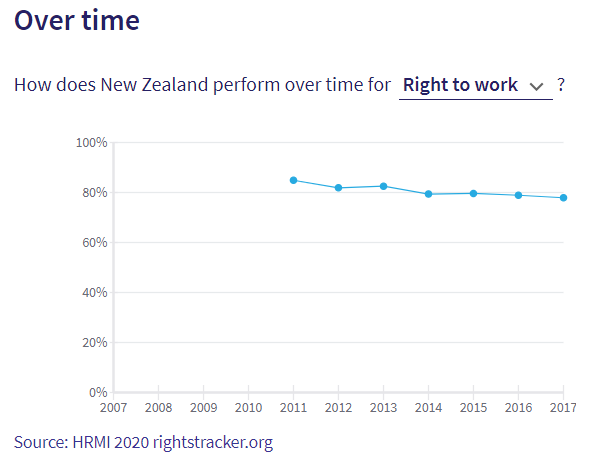

Data are available for New Zealand’s right to work score each year from 2011 to 2017. Therefore, we can use the Rights Tracker over time graph to observe a downward trend in right to work outcomes for New Zealanders over a six year period.

If New Zealand were operating at its full potential given its current resources, it could lift 280,000 people out of relative poverty, meaning their equivalised disposable household income would be above 50% of the total population median income.

Right to Housing

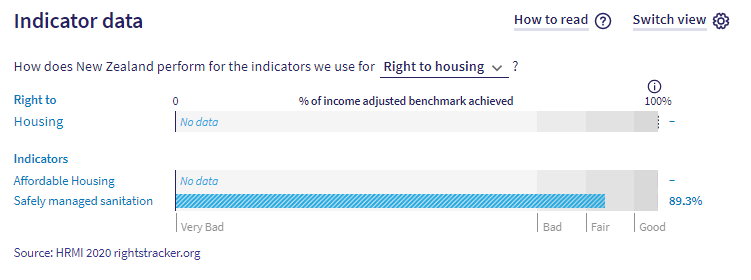

The right to housing score is based on two indicators: affordable housing, and safely managed sanitation. Comparable data for affordable housing in New Zealand isn’t available so we are unable to produce an overall score for the right to housing.

The second indicator is the percentage of the population with safely managed sanitation (score = 89.3%). Safely managed sanitation relates to the use of improved sanitation facilities that separate excreta from human contact and that are not shared with other households. New Zealand’s score falls into the fair range.

This indicator relates to SDG 6: Clean Water and Sanitation

Based on these income adjusted indicator scores, our analysis tells us that:

If New Zealand used its resources effectively, an additional 500,000 people could safely manage their sanitation with the use of improved facilities.

Māori suffer high levels of human rights violations

Having suffered the effects of colonisation and oppression for centuries, Māori are still in the position of suffering widespread human rights abuses. Māori were identified by experts we surveyed as being particularly vulnerable to abuses of nearly every one of the rights we measure.

Disabled people suffer wide range of human rights violations

Our human rights experts identified disabled people as being at particular risk of violations of most of the rights we measure, particularly:

- the right to education

- the right to housing

- the right to health

- the right to work

- the right to food

- the right to freedom from torture and ill-treatment

The summaries of qualitative responses also made clear that some respondents were concerned about those with mental health difficulties. For more detail, please see the Quality of Life, Safety from the State, and Empowerment tabs, which each have summaries of what experts told us.

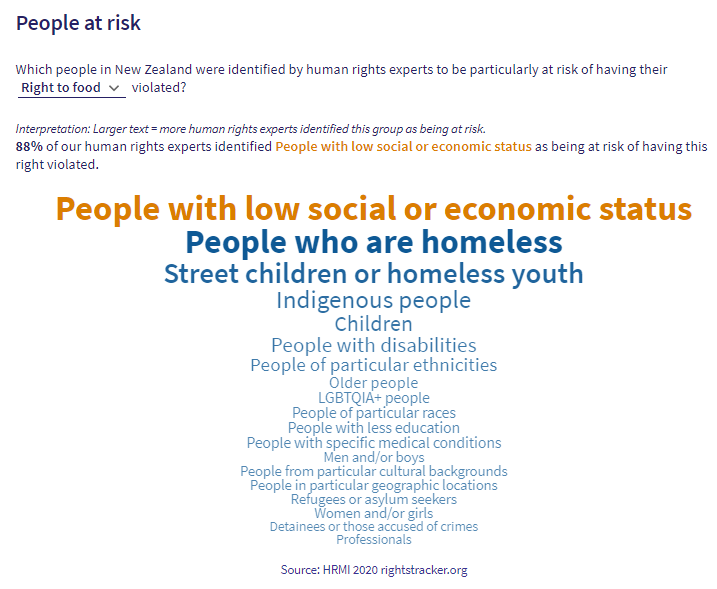

Poverty and inequity behind human rights violations

Our respondents repeatedly identified people with low social or economic status as particularly vulnerable to rights abuses and to not enjoying their full rights to basics like food, health, housing, and education.

Experts highlight threats to the rights of children and young people

Children were identified as being particularly vulnerable to abuses of these rights:

- the right to food

- the right to housing

- the right to health

- the right to education

- the right to participate in government

- the right to freedom from torture

For the first time this year HRMI included ‘street children and homeless youth’ as a group respondents could choose. Experts said that street children and homeless youth in New Zealand were at risk of many human rights violations, including of:

- the right to food

- the right to housing

- the right to health

- the right to education

- the right to participate in government

- the right to freedom of opinion and expression

- the right to freedom of assembly and association

- the right to freedom from torture

For more detail on all of these, please see the ‘people at risk’ tab, and the Quality of Life, Safety from the State, and Empowerment tabs, which each have summaries of what experts told us.

Next steps: what can you do now with this information?

If you are advocating for human rights in New Zealand, or working towards the SDGs, HRMI data can point out new opportunities for progress. Here are some ways you can use our data to encourage progress:

1. Look for the countries that are similar to New Zealand in income, but scoring much better. You can filter the rights pages on our Rights Tracker by region and income level, so just click on these rights to get started, and choose a filter at the top left: right to education, right to food, right to health, right to housing, and right to work.

You can find which countries have similar levels of income using this list, arranged by GDP per capita.

2. Ask what those similar and high-performing countries are doing differently.

3. Copy key facts from the Rights Tracker and this article to use in your reports and advocacy. Isn’t it compelling to tell the government, or the public, that with better management, 38,000 more children could live past their fifth birthday?

All our data are freely available for you to use. We would love to hear if you use our work!

4. Watch out for the next annual update of the scores in May or June each year – is New Zealand improving, either in its score or its place on the table?

5. Get in touch with us if you need any help at all. We would be delighted to partner with you in your work to improve people’s lives.

Thanks for your interest in HRMI. To further explore our human rights data for New Zealand, please visit our Rights Tracker, where you can find data by country or right.