Jamal Khashoggi and the human rights landscape of Saudi Arabia

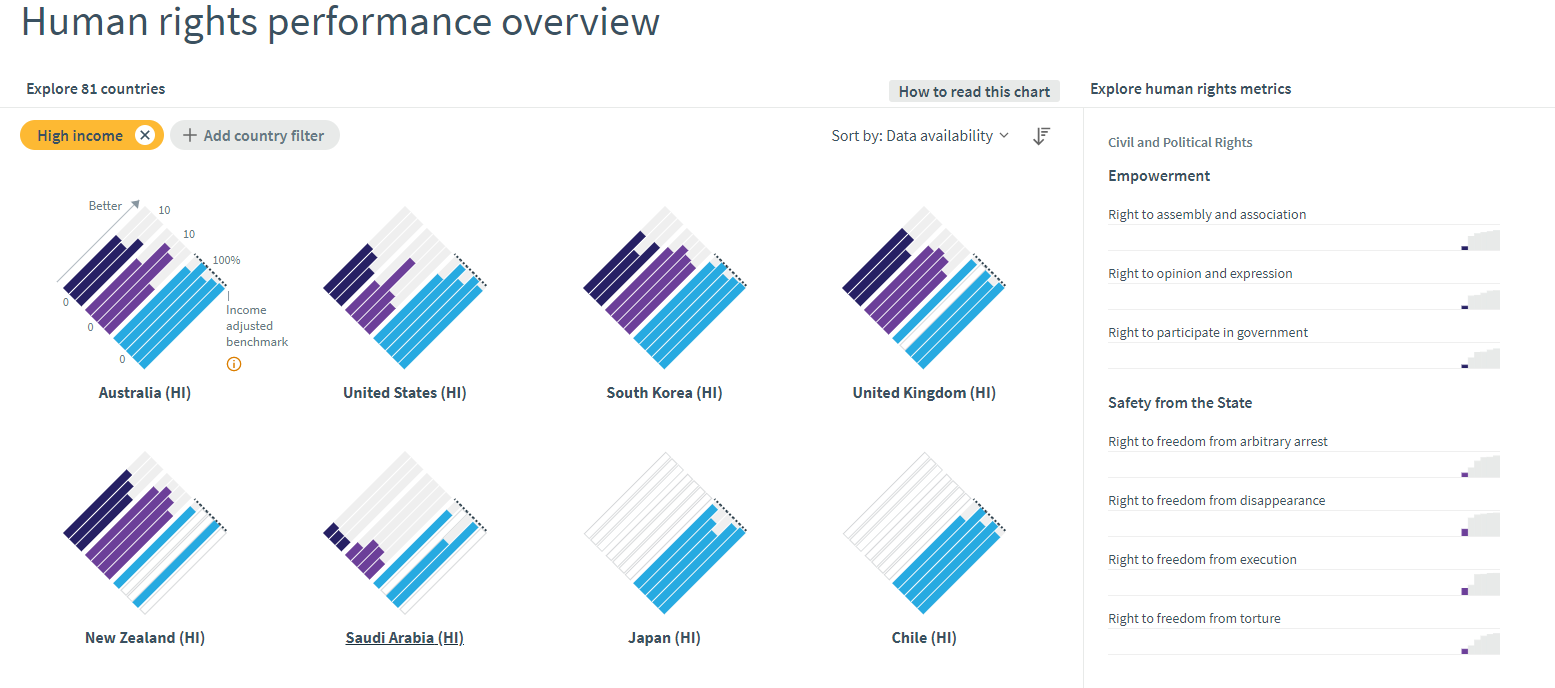

The Human Rights Measurement Initiative (HRMI) is the first global initiative to track the human rights performances of countries. This case study focuses on the economics and social rights outcomes for Saudi Arabia, and can be treated as a press release for media. All data discussed below are available on our Rights Tracker. See also HRMI’s Research credentials. This country spotlight refers to data published in 2019.

The Disappearance of Jamal Khashoggi

On 2 October 2018, the United States-based Saudi journalist, Jamal Khashoggi, went into the Saudi consulate in Turkey to get documents for his upcoming marriage. He left his phones with his fiancée outside the consulate, and never came out.

Human Rights Watch reported:

Khashoggi, 59, entered the Saudi consulate in Istanbul on October 2, 2018, and has not been seen or heard from since. Saudi Arabia has denied involvement in Khashoggi’s disappearance, claiming he left the consulate alone shortly after his arrival, but has produced no evidence to support the claim.

On October 7, Yasin Aktay, an adviser to President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan of Turkey, told Reuters he believed that Khashoggi had been murdered inside the consulate, and that a group of 15 Saudi men were “most certainly involved.” On October 9, The Washington Post reported that US intelligence officials had intercepted Saudi communications revealing a plot to capture Khashoggi.

“There is a mountain of evidence implicating Saudi Arabia in the enforced disappearance and potential murder of Jamal Khashoggi, and as the days go by, Saudi Arabia’s fact-free denials are becoming indictments in and of themselves,” said Sarah Leah Whitson, Middle East director at Human Rights Watch. “If Saudi Arabia is responsible for Khashoggi’s disappearance and possible murder, the United States, United Kingdom, European Union, and other Saudi allies need to fundamentally reconsider their relationship with a leadership whose behavior resembles that of a rogue regime.”

Saudi authorities have escalated repression against dissidents and critics since Mohammad bin Salman became crown prince in June 2017.

[Read more at Human Rights Watch.]

What HRMI data on Saudi Arabia show

Because Saudi Arabia was one of the 19 countries in our civil and political rights survey, we have extensive, recent data on its human rights performance, including information on the vulnerability of journalists, and Saudi Arabia’s practice of disappearance and extrajudicial killing.

Saudi Arabia is the worst performer in our sample

Of the 19 countries in the survey, Saudi Arabia ranks 18th or 19th – second-worst or worst – on almost all of the seven civil and political rights we measure.

When you view all high-income countries in the survey and hover over Saudi Arabia, its rank among these survey countries is highlighted in the right-hand sidebar for each right.

Freedom of expression and opinion in Saudi Arabia

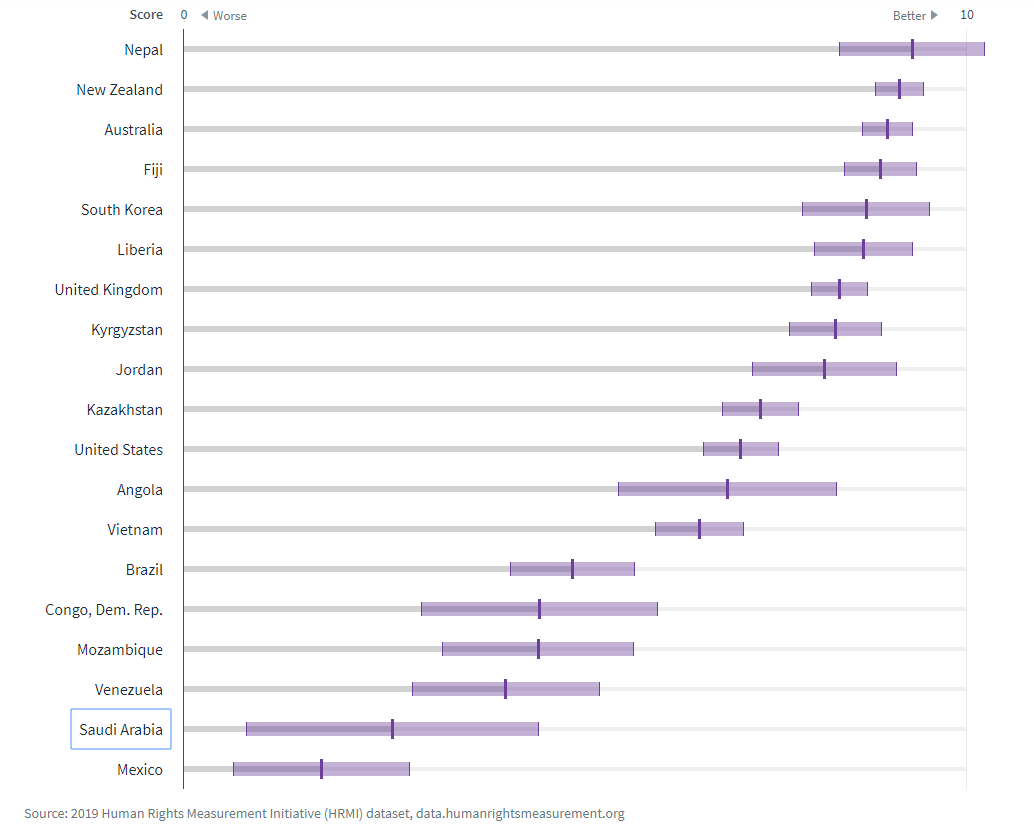

Saudi Arabia is the worst performer in the study on the right to freedom of expression and opinion, with a score of 1.1/10 (graphic and data here).

Freedom from execution in Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia is one of the worst performers in the study on the right to freedom from execution – this includes both death penalty criminal cases and extrajudicial killings (graphic and data here).

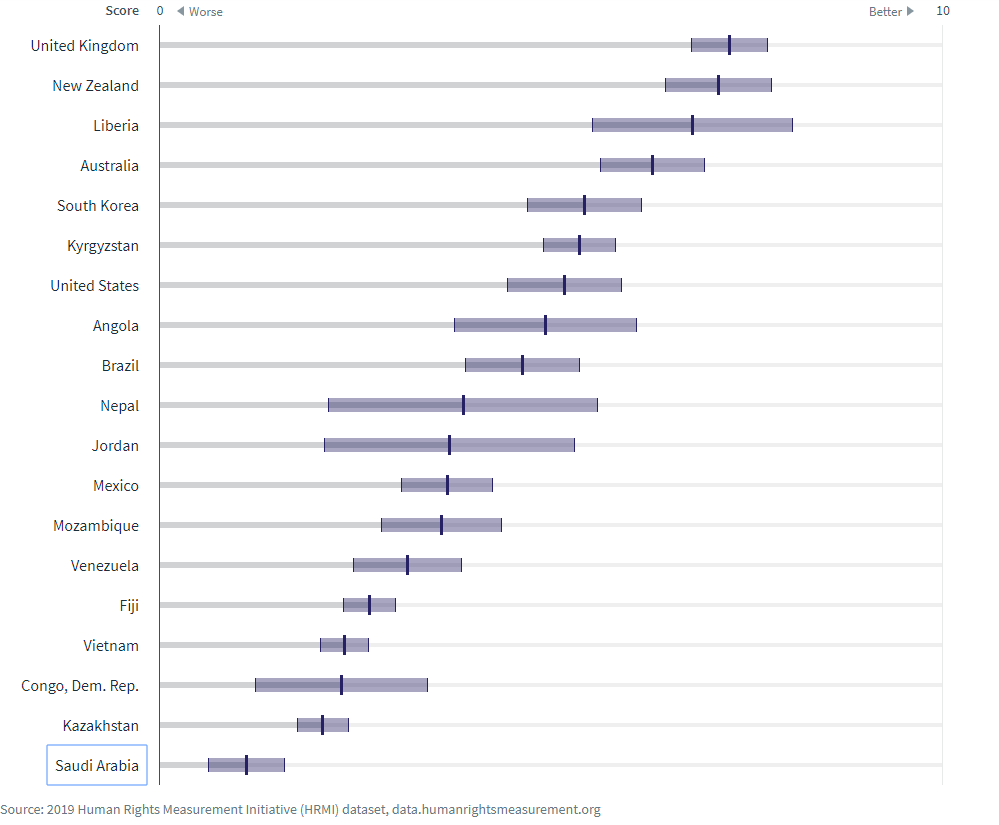

On our data site, you can further break down this right into countries’ performance on respecting the right to freedom from the death penalty and the right to freedom from extrajudicial killing (which is what is alleged to have happened to Jamal Kashoggi). Saudi Arabia’s score is 2.6/10 for freedom from execution, by far one of the worst among the survey countries.

If Jamal Khashoggi has been killed by Saudi state actors without a trial, this is ‘extrajudicial killing’. In HRMI data, Saudi Arabia’s score for respecting the right to be free from extrajudicial killing is 4.1/10. For comparison, New Zealand’s score on this right is 8.6/10 and Mexico’s score is 2.9/10.

It is possible that Saudi Arabia has a better score on extrajudicial killing than Mexico partly because it regularly uses the death penalty, carrying out around 150 executions a year (link no longer available), so has less ‘need’ to resort to extrajudicial killing.

Freedom from disappearance in Saudi Arabia

Jamal Khashoggi has disappeared. He was last seen in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul, and no one knows where he is now. According to international law, everyone has the right to freedom from ‘arrest, detention, abduction or any other form of deprivation of liberty’ followed by a lack of acknowledgement that this has occurred or ‘concealment of the fate or whereabouts of the disappeared person’.

Whether Jamal Khashoggi is still alive, and in Saudi custody, or not, if Saudi Arabia is responsible, then it is breaching his right to be free from disappearance.

Disappearances include all cases in which people are taken and their location or status is unclear, including those known to be held in secret and/or incommunicado detention (International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance, Part I, Article 2). Whether Jamal Khashoggi is still alive, and in Saudi custody, or not, if Saudi Arabia is responsible, then it is breaching his right to be free from disappearance.

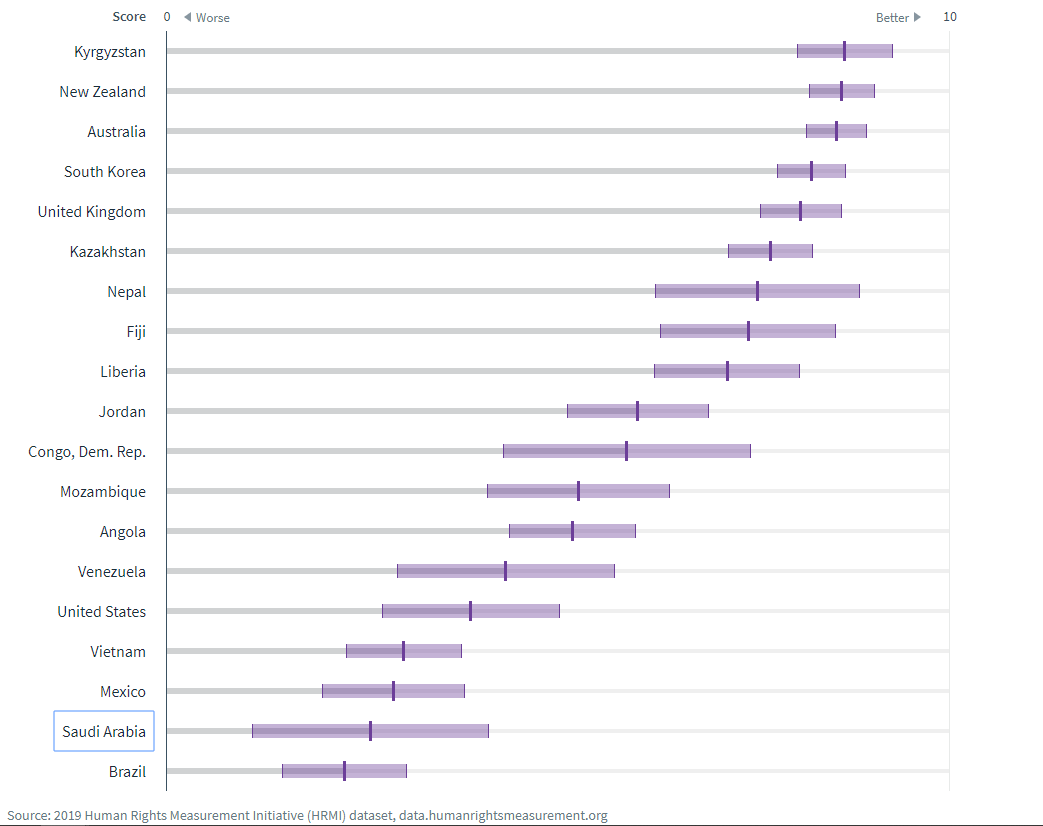

In HRMI’s data, Saudi Arabia and Mexico are the worst performers on the right to freedom from disappearance. Saudi Arabia has a score of 2.7/10 (graphic and data here), and Mexico scores 1.8/10, but the overlap of the bars in the graph below shows that there is some uncertainty about which of these two countries is in fact the worst. It is clear from our data that the two countries are the worst performers of the 19 survey countries.

Journalists are at particular risk of disappearance in Saudi Arabia

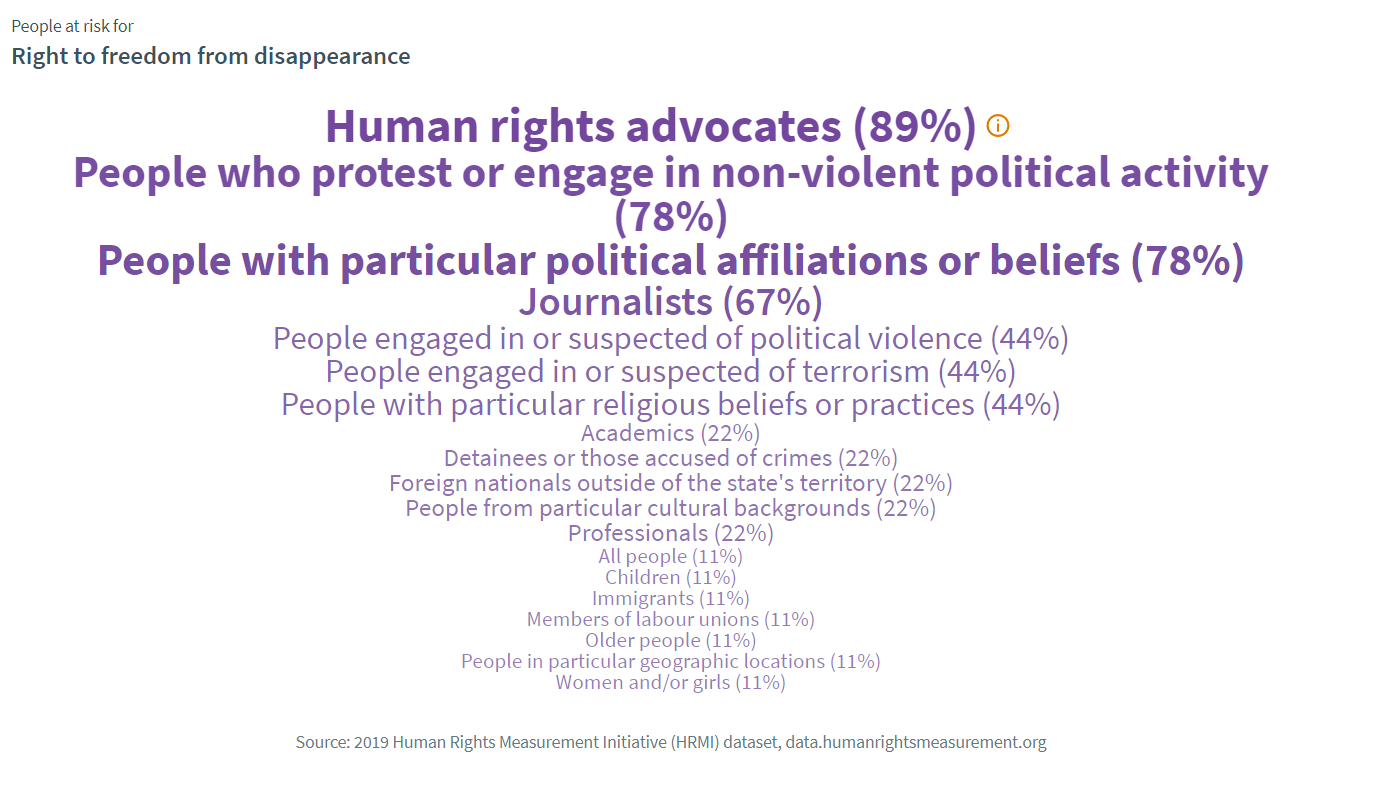

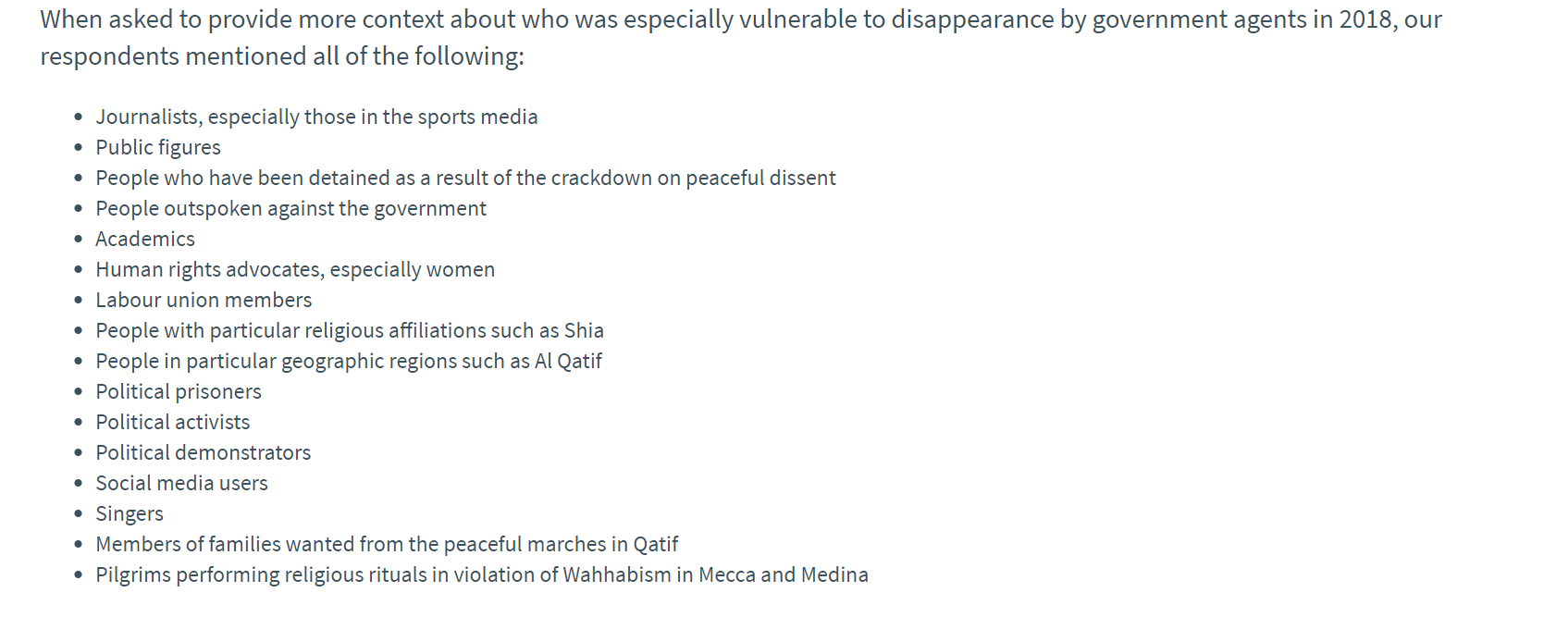

Our data show that journalists in Saudi Arabia are at particular risk of being victims of disappearance (graphic and data here; click on ‘Saudi Arabia » and the word cloud will open).

In our civil and political rights data collection, we ask human rights experts which groups they see as being most at risk of having their rights abused or limited. Their answers are represented in word clouds on our data site.

Group names shown in a bigger type are those that were selected by a larger proportion of our experts as being at particular risk.

Here is the word cloud for the right to freedom from disappearance in Saudi Arabia:

Journalists also feature in several other of the word clouds for Saudi Arabia, indicating that they are also at risk of political arrest and violations of their rights to freedom of speech.

Who can use these data?

All of HRMI’s data are freely available to anyone. You can explore our data site here, and even download the dataset.

We have data on seven civil and political rights: as well as five economic and social rights.

HRMI aims to produce useful data. Some of the people we expect will use our data are:

- Journalists, especially those reporting a particular country, and those focusing on human rights, politics, social issues or international affairs

- Researchers

- Government policy advisers

- Human rights advocates

- NGOs

- Human rights monitors within a region, and at the international level

- Companies, for decision-making, to minimise risk for investors, and direct capital flows ethically.

If you know anyone in those categories, please let them know about HRMI, in case our data can be useful to them.

HRMI’s data have been available for only a few months so far, but as different people use them, we want to share stories and case studies. Whenever you see our data in action, please tell us, and we’ll include a link on our website.