Mexico: new data show serious human rights challenges

Este artículo también se puede leer en español. Cambia el idioma usando el menú desplegable de arriba.

This country spotlight refers to data published in 2019. For the most recent data, go to our Rights Tracker.

How a border wall will increase drug cartel violence

Media stories of disappearances, arbitrary and illegal arrests, and extrajudicial killings are now so commonplace in Mexico that they almost seem normal. But the Human Rights Measurement Initiative’s new data measuring respect for civil and political rights in Mexico show that this situation is not normal at all.

Indeed, Mexicans know this is far from what they deserve, and protest loudly. There were huge protests when 43 students from a teacher training college were forcibly disappeared at the hands of police and organised crime in September 2014, and again when leading investigative journalist Javier Valdez was killed in broad daylight in May 2017.

These are just a couple of the most prominent cases of serious human rights violations that have occurred in Mexico. In 2017 alone, 12 journalists and media workers were killed and more than 34,000 people remain registered as missing.

The Human Rights Measurement Initiative (HRMI) now puts those stories into a broader context of Mexico’s human rights performance. In our study of civil and political rights over 19 countries, HRMI has found that Mexico has poor scores on each of the seven rights we measured.

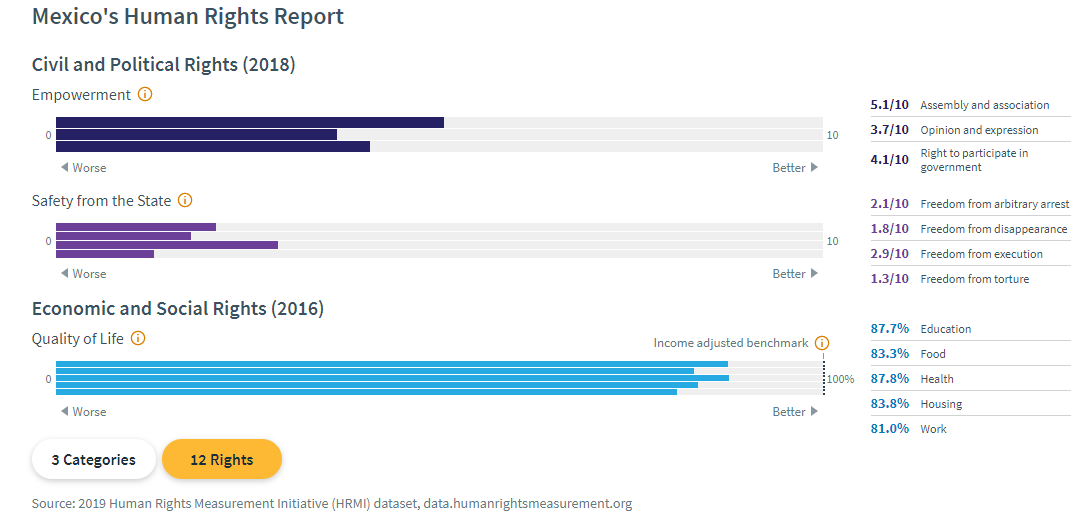

The chart below summarises Mexico’s performance across 12 human rights. In this chart, each row represents a right. The higher the country’s score is (longer in row length), the better the performance of the country on that human right.

Scores for the seven civil and political human rights are divided into two sub-sections: Empowerment and Safety from the State (both sections in different shades of purple). The scores for the five economic and social human rights are categorized under a subsection titled Quality of Life (this section in a shade of blue).

Mexico’s score for freedom from disappearance

Clearly Mexico is having real problems securing its people’s civil and political rights. HRMI exists to reveal these problems, and encourage states to improve.

You may be surprised to discover that HRMI is filling a gap: before now there was no comprehensive international database tracking human rights compliance.

In 2019, we expanded to 19 countries. With more funding, we could cover the rest of the world in 2020. Please get in touch if you are interested in funding our expansion.

It is difficult to measure civil and political rights violations, because they often take place in secret and are denied by the people who order and carry them out. Often states don’t keep any records of their own civil and political rights performance.

Since there are no objective statistics on most of these rights, we surveyed human rights experts in Mexico, and in our 18 other countries, and calculated scores based on their responses.

In 2019, we expanded to 19 countries. With more funding, we could cover the rest of the world in 2020. Please get in touch if you are interested in funding our expansion.

If you’re interested in exactly what we ask our survey respondents, you can fill out a simulated survey yourself in any of six languages. Click here to start the survey. (This is a simulation only and your responses won’t count for our data collection.)

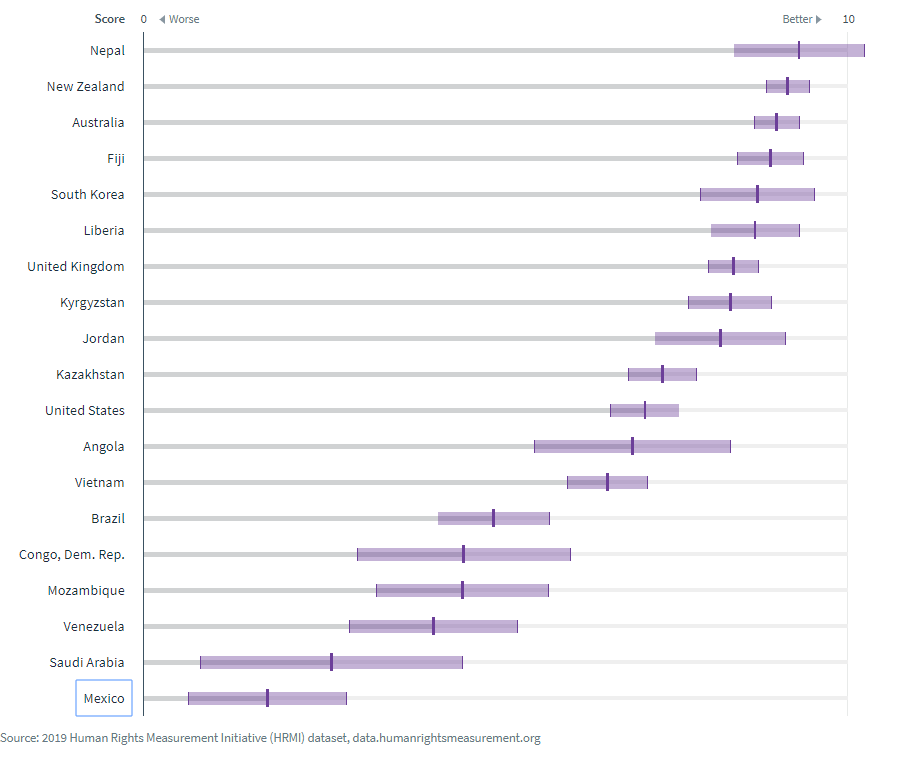

The chart below explores in more detail one area where Mexico performs particularly badly – the right to freedom from disappearance. Mexico’s performance on this human right is compared with that of the 18 other countries in our survey sample for measuring civil and political rights.

According to international law, everyone has the right to freedom from ‘disappearance’, that is, arrest, detention, abduction or any other form of deprivation of liberty, followed by a lack of acknowledgement that this has occurred or ‘concealment of the fate or whereabouts of the disappeared person’. Disappearances include all cases in which people are taken and their location or status is unclear, including those known to be held in secret and/or incommunicado detention (International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance, Part I, Article 2).

Normally, we wouldn’t compare 19 such different countries, of course. However, we tested our methods to make sure they work in all kinds of different settings: large and small countries, with a range of wealth, from different parts of the world. Our plan is to repeat our data collection every year, and include more countries as our funding increases. Then we’ll be able to show the progress each nation makes in human rights performance over time, and compare similar countries. When we have enough data, we will present scores for Mexico in comparison with other Latin American countries, for example, as well as Mexico’s past scores.

You can see that Mexico’s disappearance score is significantly worse than the score for Brazil (another Latin American country in the sample). It is also on par with Saudi Arabia’s score, as shown by the overlap of the purple bars of these two countries.

This finding is not surprising given the rise in disappearances in Mexico, perpetrated by both state and non-state actors (as defined by the UN International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance).

This increase has been especially notable since 2009 following the federal government’s launch, a year or two earlier, of its militarised strategy against drug cartels. Making a person ‘disappear’ has become a common technique for both government authorities and members of organised crime, who often act together (for example, as documented in the Zetas Piedras Negras prison case).

HRMI measures human rights performance by the state, not private citizens, but when the state encourages, ignores or collaborates with others, such as organised crime groups, those disappearances are included in our data.

The Mexican government has an incomplete register of people who have been subjected to disappearance or who went missing for another reason. According to that official source, there were 34,674 missing people in the country as of November 2017.

Mexico’s best CPR score: the right to assembly and association

By contrast, Mexico’s best score in the area of civil and political rights is for the right to assembly and association (average score of 5.1 out of 10). On this human right, Mexico is closer to the middle of the pack when compared to the other 18 countries in the survey.

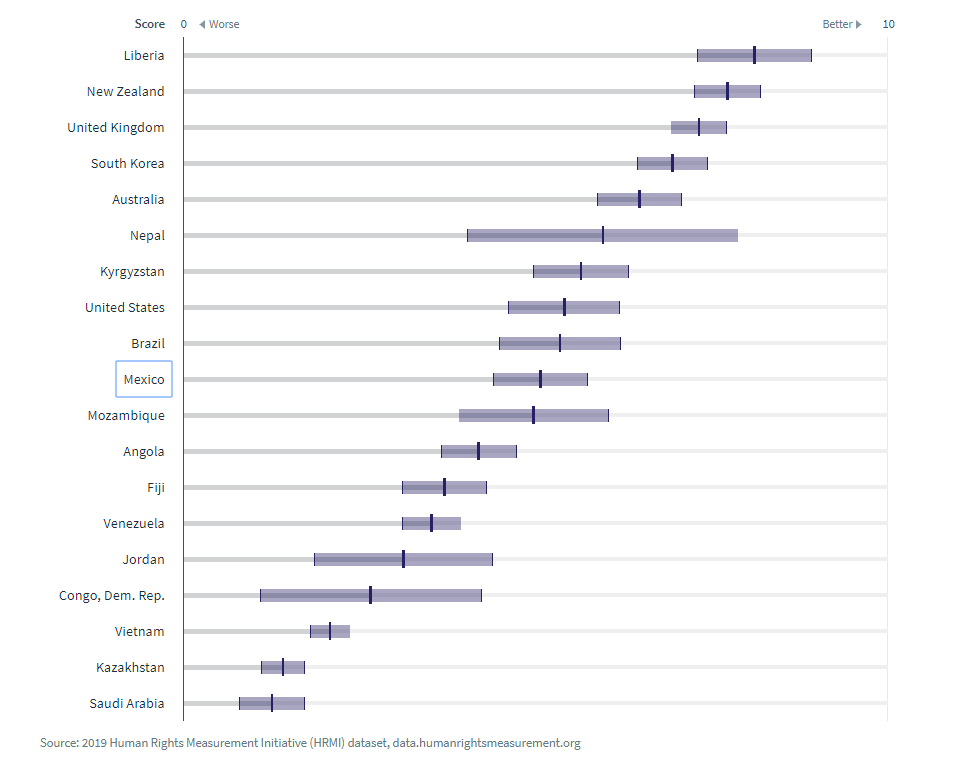

In order to illustrate this, consider the chart below, which compares scores for the right to assembly and association across countries in our survey. For this human right, Mexico’s score is not substantially different than the scores of Nepal, Kyrgyzstan, the United States, Brazil and Mozambique.

We know this by looking at the significant overlap of the ‘bars’ for these six countries. The similarity in range of these six countries, as well as comparable average scores, suggests that these countries’ respect for the right to assembly and association is analogous (when you explore this chart at our data site you can hover over each bar and get the exact numbers). This chart also suggests that Liberia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom’s respect for this right is higher than Mexico’s.

Who can use these data?

HRMI aims to produce useful data. Some of the people we expect will find it helpful are:

- Journalists, especially those reporting on a particular country or region, and those focusing on human rights, politics, social issues or international affairs

- Researchers

- Governments

- Human rights advocates

- NGOs who want data on countries they work in

- Human rights monitors within countries, and at the international level

- Private companies, for decision-making, to minimise risk for investors, and direct capital flows ethically.

If you know anyone in those categories, please let them know about HRMI, in case our data can be useful to them.

HRMI’s data has been available for only a few months so far, but as different people use it, we want to share stories and case studies. Whenever you see our data in action, please tell us, and we’ll include it here.