Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders suffer human rights violations in Australia

This country spotlight refers to data published in 2019. For the most recent data, go to our Rights Tracker.

The Human Rights Measurement Initiative has released 2019 human rights data for Australia, with some disturbing results:

- Australia scores only 5.5 out of 10 for freedom from torture

- Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders are identified as particularly at risk of violation of all 12 human rights HRMI measures

- Refugees and asylum seekers are also at heightened risk of a range of abuses

- Disabled people are at extra risk of rights violations.

HRMI is the first global project to track the human rights performance of countries. Its 2019 Human Rights metrics give human rights scores on up to 12 different human rights contained in United Nations treaties, for over 180 countries.

HRMI’s 2019 data on Australia contain many positive scores, but also some strikingly poor results, particularly in terms of who is most at risk of rights abuses.

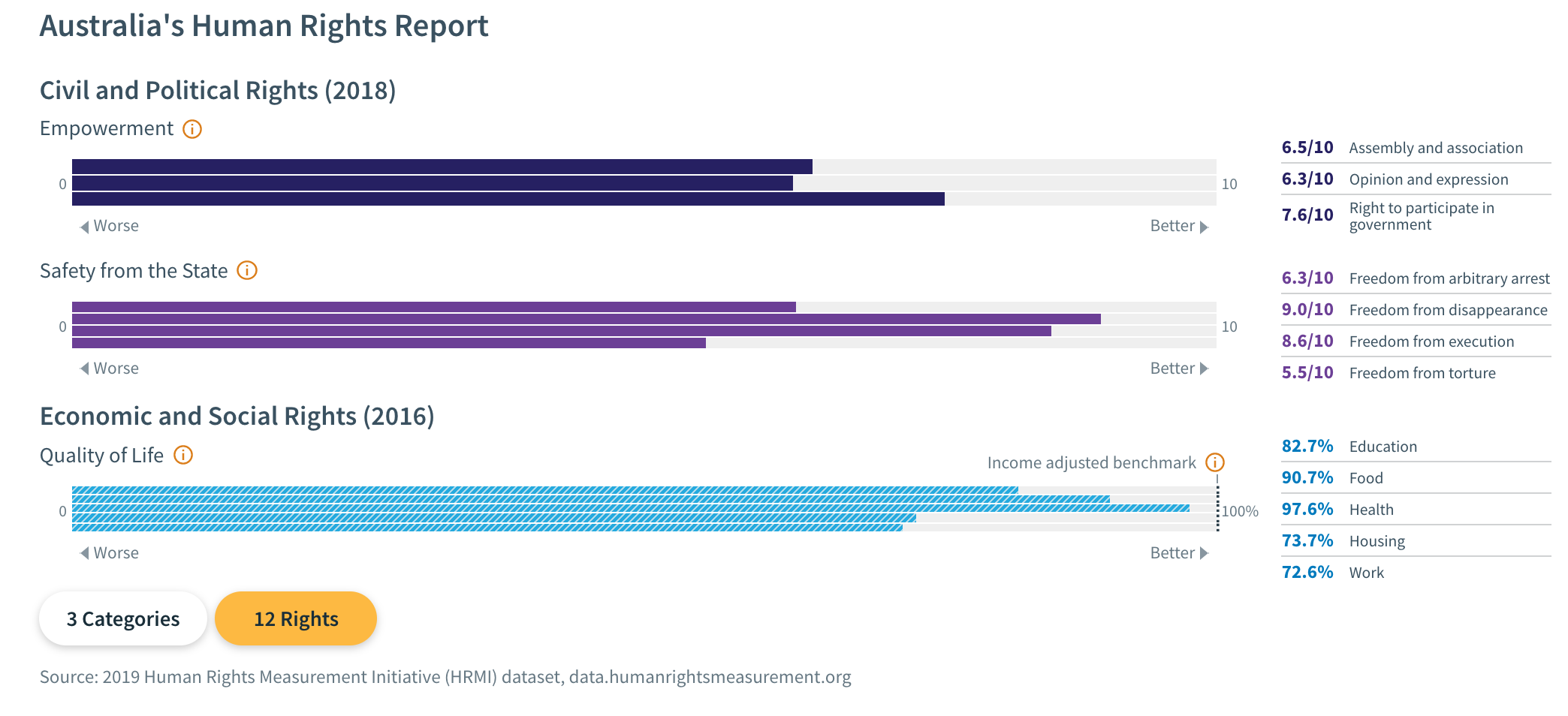

The 12 rights are summarised by three category scores:

Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders suffer rights abuses

Having suffered the effects of colonisation and oppression for centuries, Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders are still in the position of suffering widespread human rights abuses. The Indigenous people of Australia were identified by experts we surveyed as being particularly vulnerable to abuses of every single one of the rights we measure.

For example, the word cloud below shows that 56% of respondents identified Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders as particularly at risk of being arbitrarily arrested or detained.

Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders are among the most incarcerated people in the world. HRMI’s data suggests that many of these people are imprisoned in a way that violates their human rights.

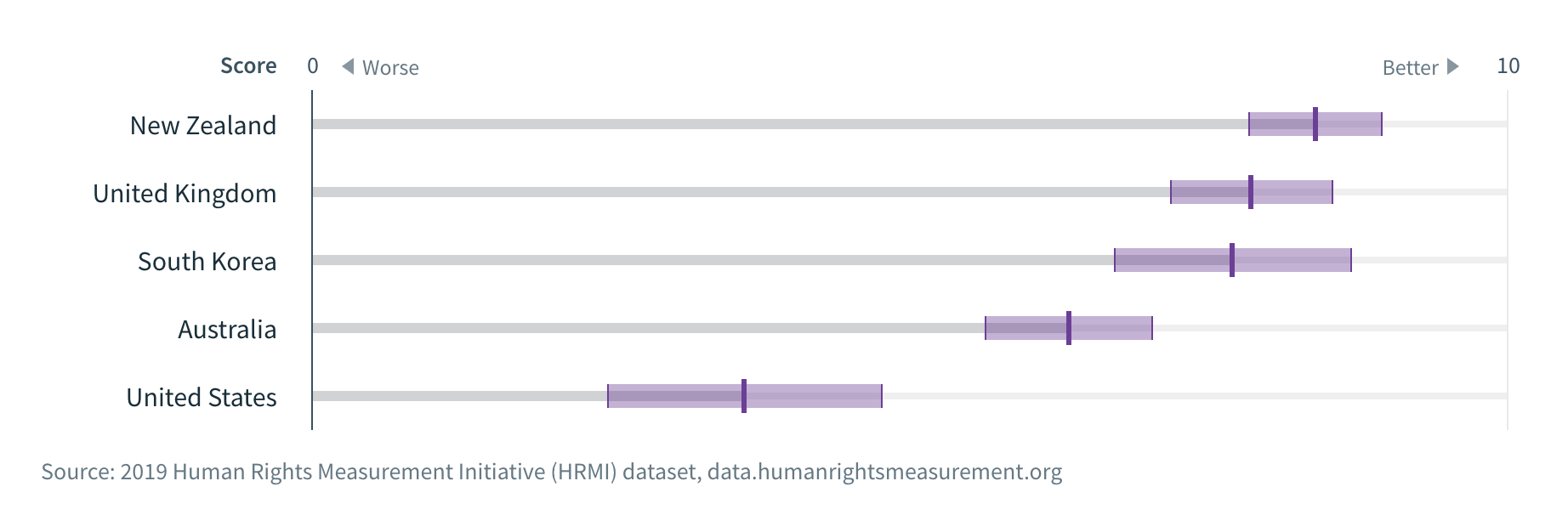

It is also notable that among the high income OECD countries we scored, Australia outperforms the United States, but lags behind New Zealand, the United Kingdom and South Korea on some rights, such as the right to freedom from arbitrary arrest.

This graph shows the performance of those countries on the right to freedom from arbitrary arrest.

Torture is a serious problem in Australia

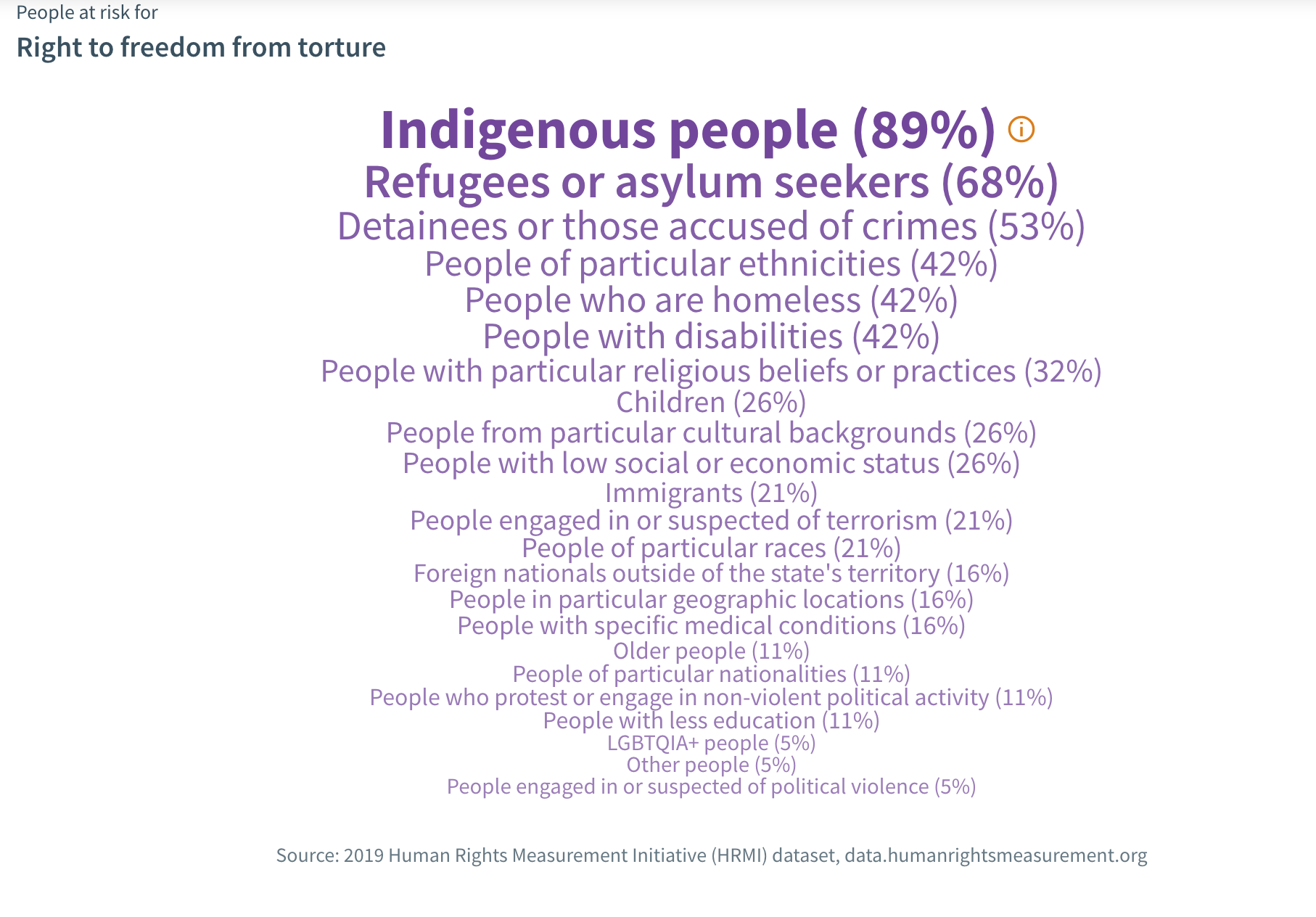

Australia received a poor score of 5.5 out of 10 for the right to freedom from torture.

Our expert respondents named a large range of people as being at particular risk of torture or ill-treatment, with Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders at the top of the list, nominated by almost all of our respondents.

Australia compares poorly on this right, too, when viewed alongside other high income OECD countries in our sample.

Marked inequities in Australians’ quality of life

For all five Quality of Life rights we measured (the rights to food, education, health, housing, and work), Australia has some way to go to meet its human rights obligations. It is also concerning that our expert respondents provided long lists of people who were especially at risk of not enjoying these rights.

The Quality of Life overall score is a measure of how well a country uses its wealth to ensure people’s rights to food, education, health, housing and work are met. The score is produced by using data from international databases, and measuring outcomes against a country’s income level.

Because the score takes income into account, every country should achieve 100%.

HRMI co-founder and economic and social rights lead Dr Susan Randolph explains that, ‘Australia’s income adjusted Quality of Life score of 83.4% implies that with the resources it has, Australia can do much more than it currently is to ensure its people enjoy their economic and social rights. As such, it has a long way to go to meet its obligations under the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights.’

Dr Randolph points out that ‘Australia ranks 14th, just below Spain and Italy, against the 22 high income countries, for which we have full data to compute the Quality of Life score. Australia turns in its best performance on the right to health, scoring 97.6% of what should be possible given its resources. However, there remain large differences in rights enjoyment across population subgroups. For example, the score for Aboriginal people and Torre Straight Islanders on our education quality indicator, performance on the PISA test, is only half as high as for other groups on average.’

Human rights practitioners who participated in HRMI’s 2019 expert survey added further information to the data analysis led by Dr Randolph.

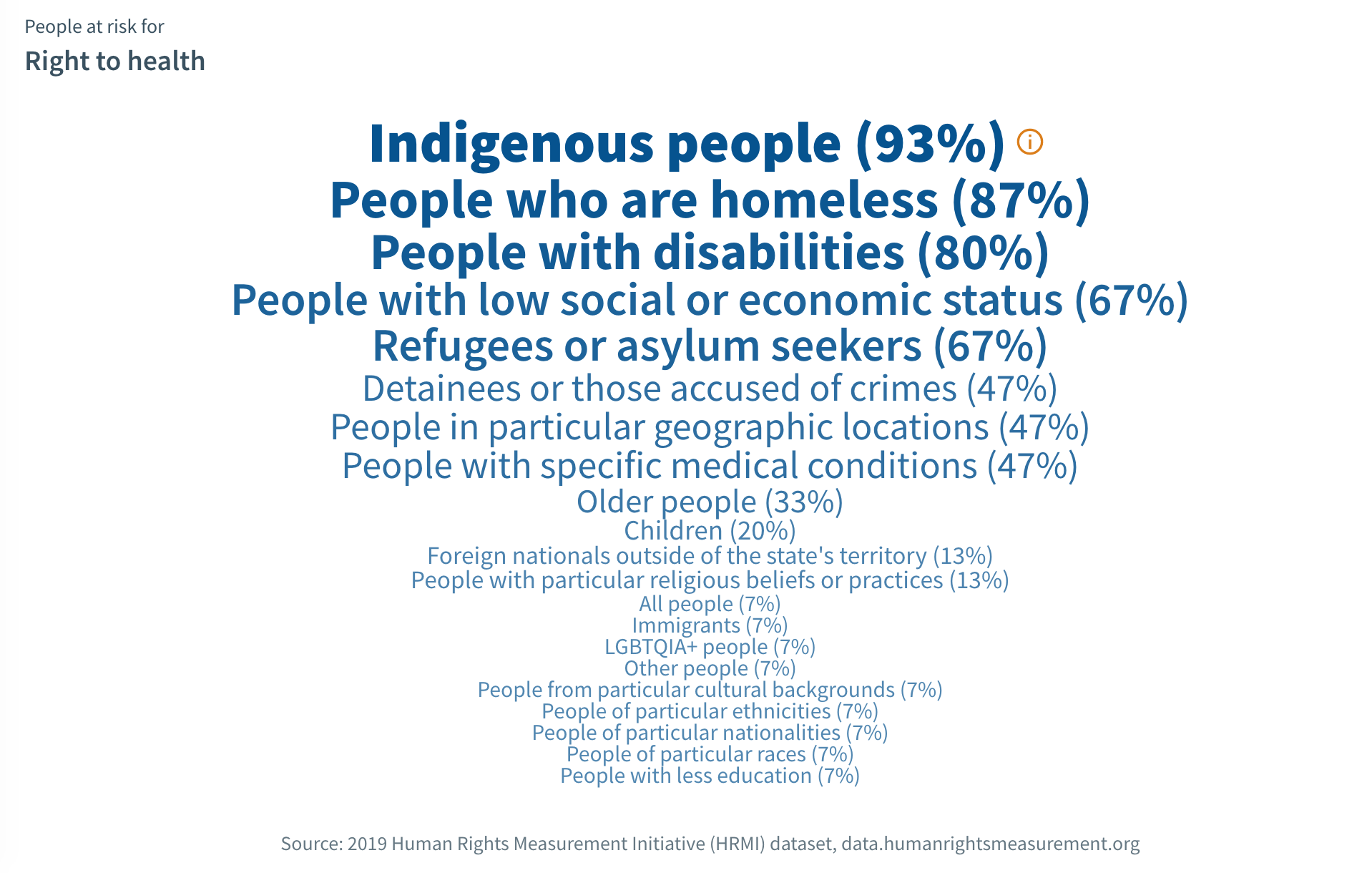

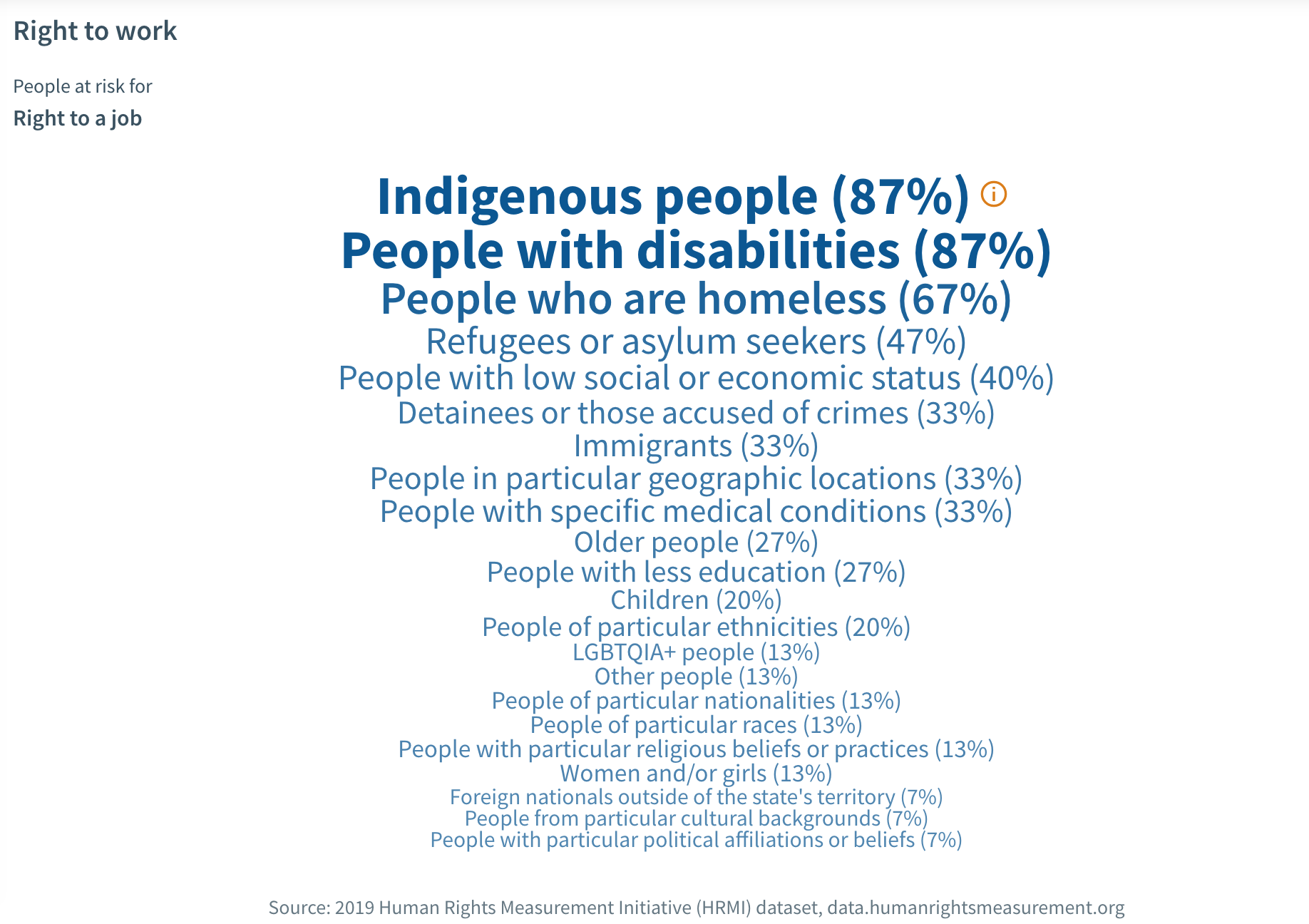

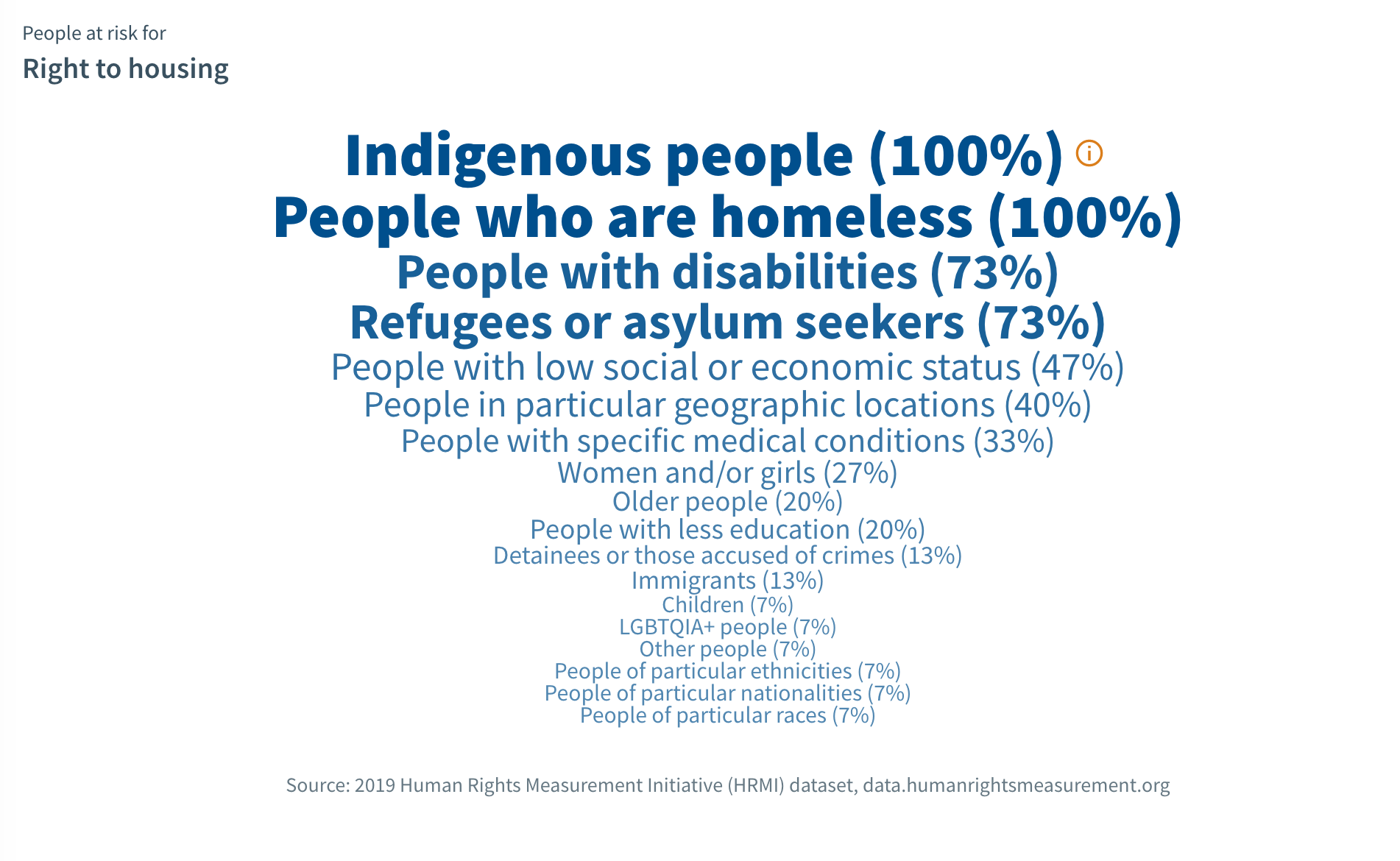

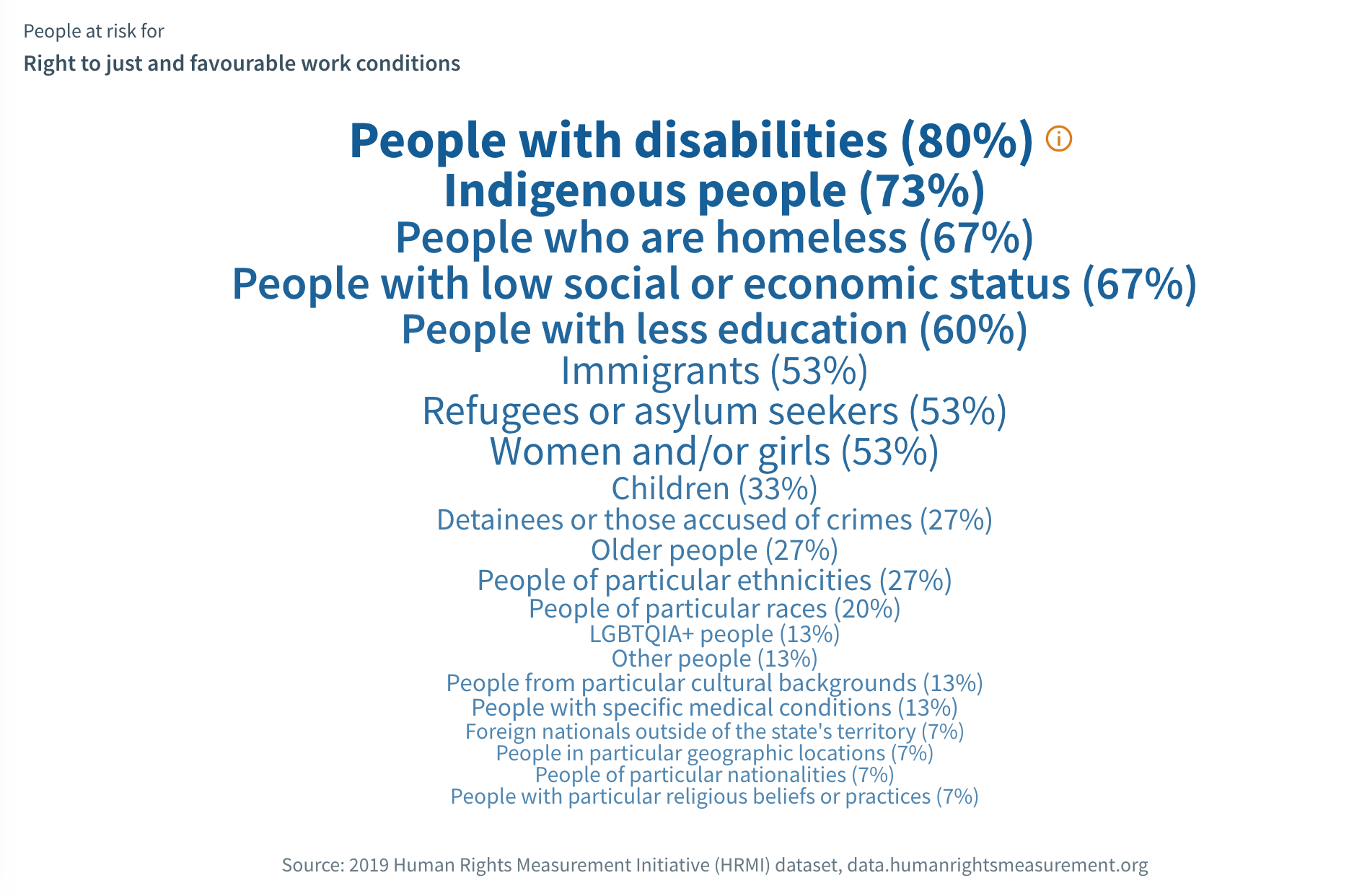

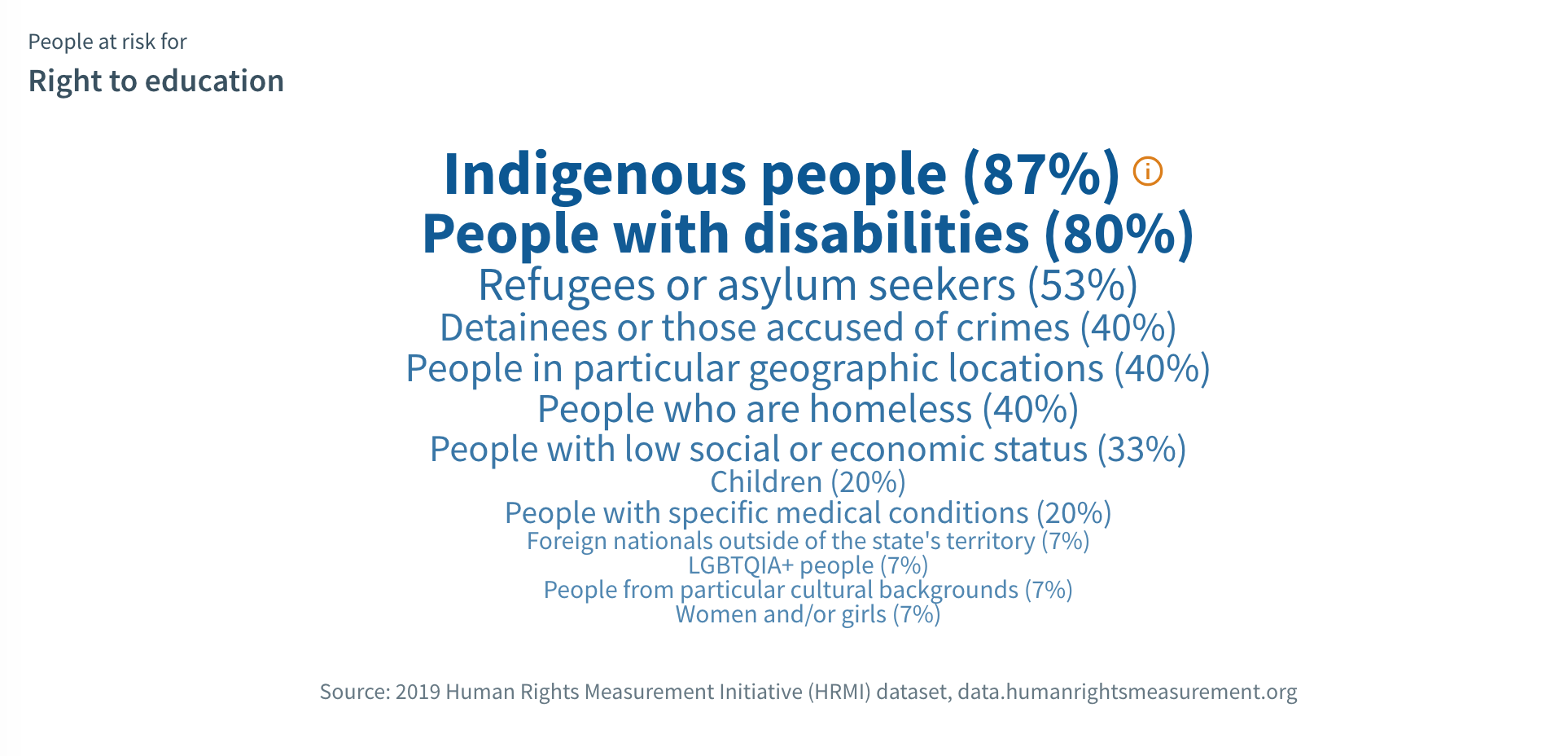

When asked to identify which groups (from a list of 32) were particularly at risk of having their economic and social rights violated, our respondents gave these answers among others. You can see the full set of answers at our data website.

(Note that the phrase ‘indigenous people’ is used because it is an international survey.)

It’s clear that Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders are much more at risk of human rights violations than people of other ethnic backgrounds in Australia, along with several other groups. The Australian government has a long way to go to meet its human rights obligations.

Australia’s treatment of refugees and asylum is also an important contributor to its poor human rights performance. You can read more about this aspect of our findings in our article here.

These are just some of the stories our data tell. Please explore the data portal yourself – by country, or by right – and let us know what you think.