Improving enjoyment of the right to housing in Chile

Este artículo también se puede leer en español. Cambia el idioma usando el menú desplegable de arriba.

The Human Rights Measurement Initiative (HRMI) is the first global initiative to track the human rights performances of countries. All data discussed below are available on our Rights Tracker.

This article refers to HRMI data published in 2020, and has been produced in collaboration with The Center for Social Research from TECHO-Chile and Fundación Vivienda.

By Pablo Santos-Pineda, Matías Reyes Labbé, Bruna Fontes, Jason Pagan, and Susan Randolph.

Despite a strong housing policy history, Chile can still make improvements

Chile has been held up as a glowing example of how the rest of the Latin American region can design and implement new pathways to ensuring the right to housing. Specifically, with its housing policies that target low income homeowners and renters, Chile has undertaken an assertive and persistent effort that not only addresses the right to housing in the country, but also indirectly helps poverty reduction.

But could Chile achieve more?

This report seeks to assess Chile’s performance in fulfilling the right to housing. We find that many additional people stand to benefit if Chile were to use the maximum of its available resources to efficiently and fairly ensure the right to housing.

As a caveat though, the most recent data available for this analysis are from 2017 and, unfortunately, do not capture the most recent effects of Chile’s ongoing social movements nor the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the right to housing. To learn more about the impact of these events on the right to housing, TECHO, a non-profit organisation, has conducted studies underscoring the rise of housing prices in the capital, Santiago and developed a national census report documenting the explosion of slums throughout the country (both currently available in Spanish only). Additionally, HRMI’s new scores, due in June 2021, will not include an update on housing affordability.

By way of a summary, this report finds that as of 2017 :

- An additional 250,000 people living in the poorest quintile of the population could have access to affordable housing if resources were allocated more appropriately.

- If Chile used its resources effectively, an additional 3.3 million could benefit from safely managed sanitation facilities.

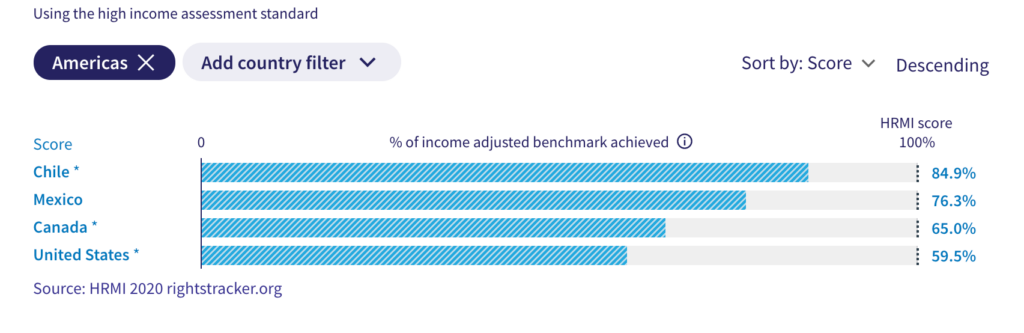

- Chile’s income adjusted performance score on the right to housing ranks number one among the four high income countries in the Americas for which we have data, outperforming both the United States and Canada. This finding implies that Chile’s government is using its available resources more effectively, relative to both the United States and Canada, in fulfilling the right to housing.

Understanding HRMI methodology and scores

HRMI data can help boost efforts to improve people’s lives in Chile by providing quantitative measures of government performance on economic and social rights (ESR) outcomes. To evaluate ESR outcomes, HRMI uses an ‘income adjusted’ benchmark to produce scores. Such scores can be used to show whether the government is doing as much as it can within the constraints of its current resources; how much improvement is needed to fulfil a given right; and the extent of rights’ performance progress or deterioration over time.

By comparing income adjusted scores on different rights and right indicators, countries can learn where the greatest improvements can be made even in the absence of economic growth, and where change is needed most. By looking to countries with similar resources but better ESR performance, countries can gain new insights into the sorts of policies and measures that are likely to improve rights outcomes.

So, how do HRMI’s income adjusted scores assess country performance on economic and social rights? HRMI’s ground-breaking methodology allows us to score countries on how well they use their income to fulfil five economic and social rights: the rights to education, food, health, housing, and work. To calculate a country’s ESR income adjusted scores we use the SERF Index methodology, developed by HRMI co-founder Susan Randolph and her colleagues Sakiko Fukuda-Parr and Terra Lawson-Remer. See: Fukuda-Parr, Sakiko, Terra Lawson-Remer, and Susan Randolph, Fulfilling Social and Economic Rights. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015.)

The SERF Index combines country achievement and country income to produce a ‘best practice’ benchmark that records the best results that countries have achieved over the last 20 years, at every income level. Each country’s current achievement level is then compared to the best practice benchmark for its income level, and the country’s ESR score is given as a percentage of that result.

For an animated explanation of how this methodology works, you can watch this short video:

The SERF methodology takes income into consideration, so it can assess all countries on a level playing field. This simultaneously reveals the areas that a country should be able to improve their rights performance in, and by how much, even without more income or resources.

When a country scores 100% on the performance of a right, it means that the government is keeping its human rights promises to do the very best for its people within the constraints of the country’s current resources. Any score that’s less than 100% shows that there’s a gap between how that country is doing, and the best result of other countries with the same level of income. An underperforming country can use HRMI’s income adjusted scores to see which of their neighbours or peers are doing better and source policy lessons from them.

However, an income adjusted score of 100% does not mean all people enjoy the right to housing, nor does it imply all population subgroups are being treated equally. Some population sub-groups may be discriminated against and, as a consequence, may find themselves not fully enjoying their rights relative to other groups.

There is a lot of cross-over between HRMI’s human rights performance indicators and the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) targets and benchmarks. Countries can use HRMI’s scores to evaluate their own progress and their potential to reach the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, given their current level of income. See: ‘Looking at the SDGs with fresh eyes: How HRMI rights data can help.’

In addition to this ‘income adjusted’ benchmark, you can also see how a country is performing relative to the ‘global best’ benchmark. This benchmark evaluates country performance relative to the best performing countries at any level of resources.

Both benchmarks are useful for different purposes. The country scores measured against the income adjusted benchmark show how effectively a country is using its resources to achieve good rights outcomes. This also tells us how much its performance can be improved even without extra income. The scores measured against the global best benchmark show how far a country has to go to do as well as any country in the world. These global best scores are important because even if a government is doing its best with their current resources (so it has an income adjusted rights score close to 100%), a country with very low income will likely still have many people not fully enjoying their human rights, which will be reflected in low scores when measured against the global best benchmark.

HRMI also uses two assessment standards when evaluating a country’s ESR performance. The assessment standard tells us which collection of rights indicators we use to evaluate the ESR performance of a country. The difference between the two assessment standards has to do with the availability and relevance of data for low and middle income countries versus high income countries.

The low and middle income assessment standard includes rights indicators which low and middle income countries are more likely to have data on, and/or which are more relevant to the rights challenges they currently face. The high income assessment standard includes rights indicators high income countries are most likely to have data on, and/or which are more relevant to the rights challenges they face.

For example, when figuring out how well countries are doing at fulfilling the right to housing, for low and middle income countries we look at ‘water on premises’ rates. This tells us about access to housing with the essential infrastructure of running water. This indicator is widely available for low and middle income countries and varies widely across them.

But in high income countries, water on premises is essentially universal, so this indicator isn’t a very useful measure of the right to housing. Instead, for our high income assessment standard we use affordable housing as a measurement of access.

We do produce scores on all indicators using both assessment standards for all countries if the data are available.

It can be useful to toggle between the two assessment standards, and check out our scores on the individual indicators, on the country pages of the Rights Tracker.

HRMI scores for Chile on the right to housing

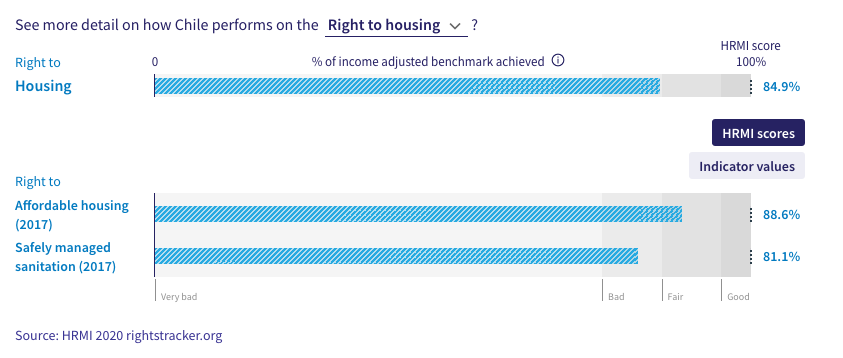

When we evaluate Chile’s right to housing performance using the income adjusted performance benchmark, which allows a comparison of what other countries with similar income levels have achieved, and using the high income assessment standards, Chile’s HRMI score is 84.9% out of 100%. This means that it has only achieved 84.9% of what it could be doing to meet its obligations to fulfil the right to housing without any additional resources.

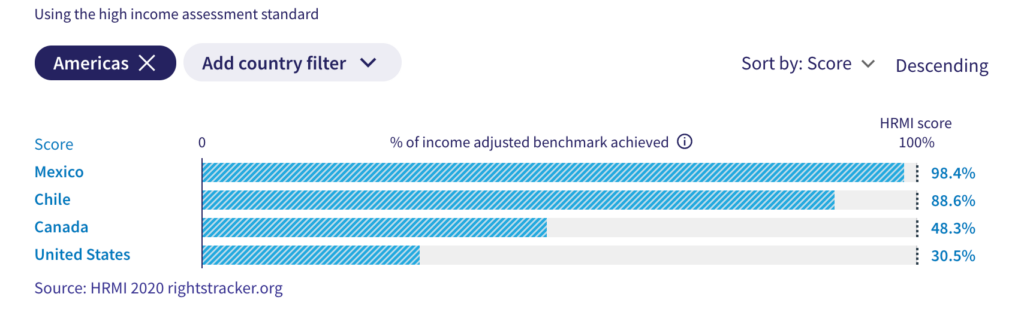

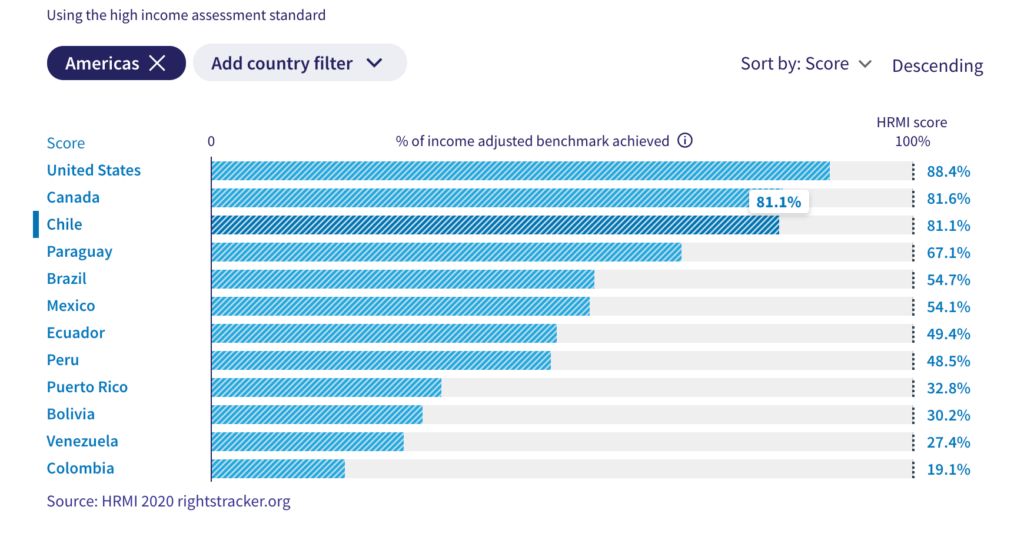

The graph above shows that Chile’s 84.9% score is explained by Chile’s performance on two indicators reflecting different aspects of the right to housing. The first one is housing affordability. We measure affordable housing using the percentage of the poorest quintile of the population who are living in a household where the cost of rent or mortgage represents less than 40% of total disposable household income (net of housing allowances). Chile’s HRMI score for this indicator is 88.6% which we rate as ‘fair’. The second aspect is housing services and infrastructure and our indicator is ‘safely managed sanitation’. Chile has a HRMI score on this aspect of 81.1% which we rate as ‘bad’.

Since any score below 100% means that a country is not meeting its obligations, Chile needs to better allocate its resources in order to improve the enjoyment of this right among its people. With an overall score of 84.9%, which is just shy of the ‘fair’ range, Chile can still do a lot more to ensure that its people can fully enjoy their right to housing. Chile’s performance on housing affordability falls squarely into the ‘fair’ range while its performance on housing services and infrastructure falls into the ‘bad’ range.

These scores are based on Chile’s data from 2017. Since then, increased internal migration into informal settlements, whose housing situation is not captured by any official government records, and the Covid-19 pandemic, have further exacerbated the situation. For more recent analysis detailing these effects, we encourage readers to refer to extensive analysis published by TECHO. Those reports are found here (housing prices) and here (increase in slums) (both only available in Spanish).

The above numbers represent the experiences of real people. If Chile made improvements, and improved from its current scores to 100%, it would mean that:

An additional 250,000 people living in the poorest quintile of the population could have access to affordable housing if resources were allocated more appropriately.

If Chile used its resources effectively, an additional 3.3 million people could benefit from safely managed sanitation facilities.

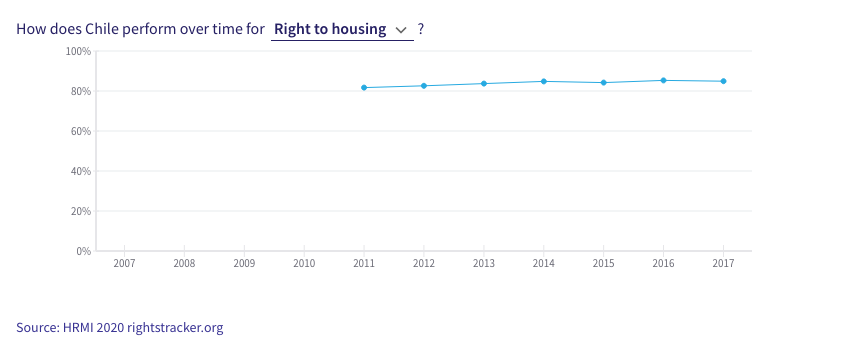

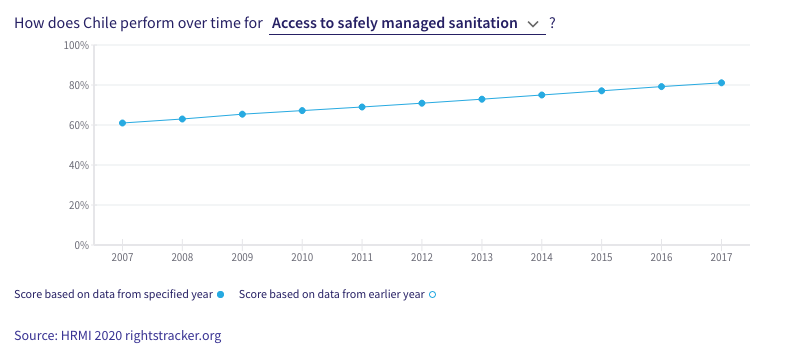

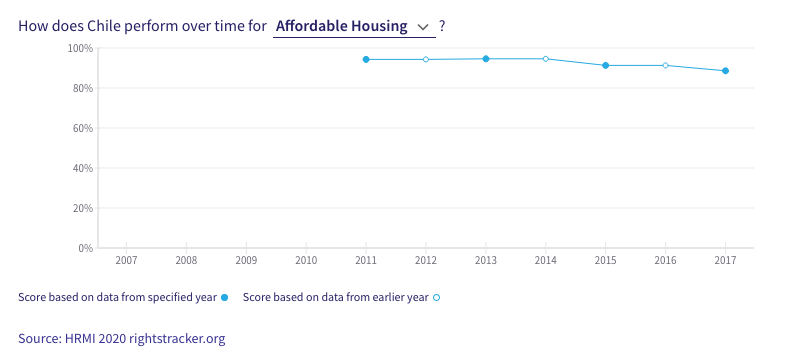

Additionally, analysing Chile’s scores over time for the right to housing, it is possible to see that its overall housing score was nearly flat over the 2007-2017 period. This flat trend is due to offsetting trends in the two sub-components, illustrated in the charts below. Scores for safely managed sanitation went up significantly between 2007 and 2017, but scores for affordable housing decreased. We are conscious that the score for housing affordability in particular, is likely to have continued to trend downward if we were able to include more recent data to capture the effects of Chile’s social movements and the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

How does Chile compare to the rest of the Americas? The OECD?

Now let us look at Chile’s right to housing performance compared to other countries in the Americas for which we have data on the high income assessment standard. What might surprise some people when looking at the data is that Chile comes in first place, outperforming both the United States and Canada using the income adjusted benchmark:

When it comes to affordable housing, as shown below, Chile is in second place, still outperforming the United States and Canada using the income adjusted benchmark:

The only area that our data shows that Chile does not perform better than the United States using the income adjusted benchmark is in safely managed sanitation, but it does perform better than all its Latin American neighbours:

This tells us that by and large, Chile is more effectively using its resources to fulfil its people’s right to housing than its North and South American neighbours. This does not mean that a greater percentage of Chile’s population enjoys the right to housing than those of its richer neighbours. To learn whether this might be the case, we can evaluate Chile’s performance using the global best benchmarks.

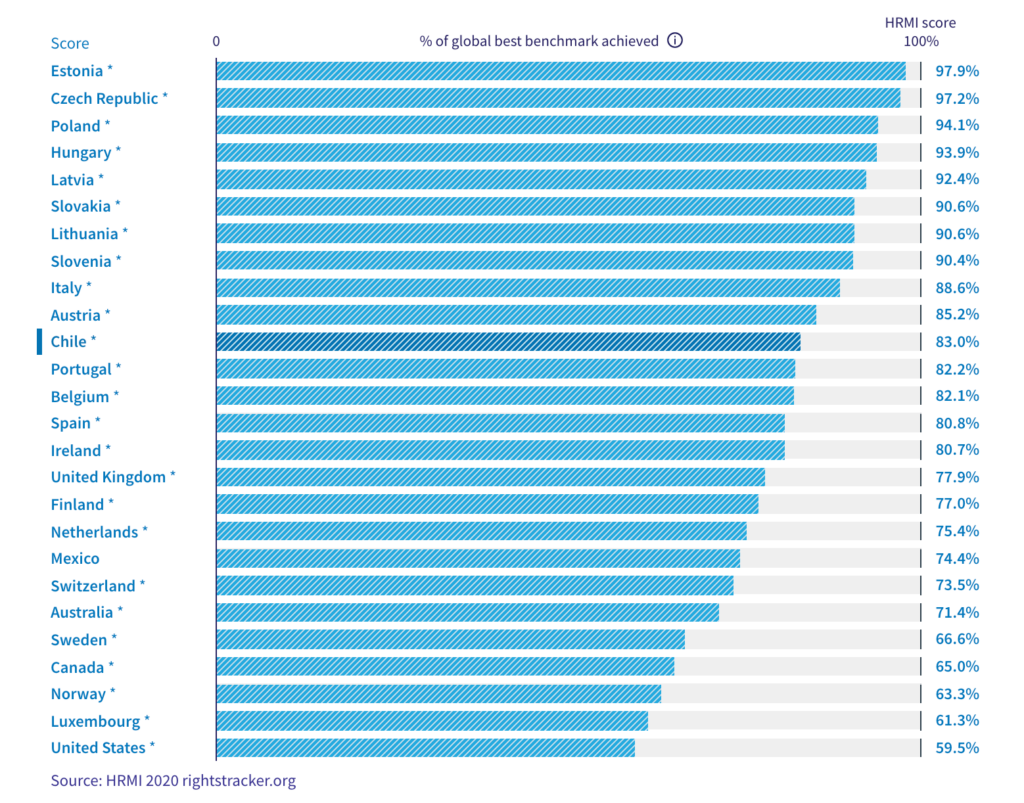

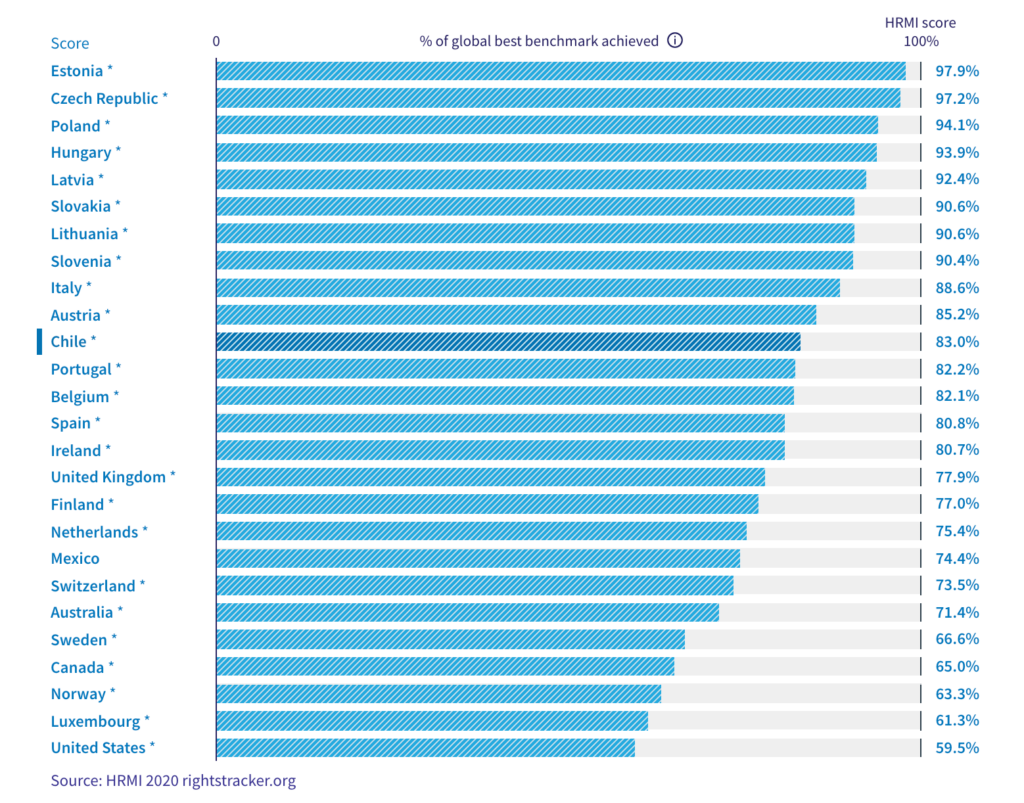

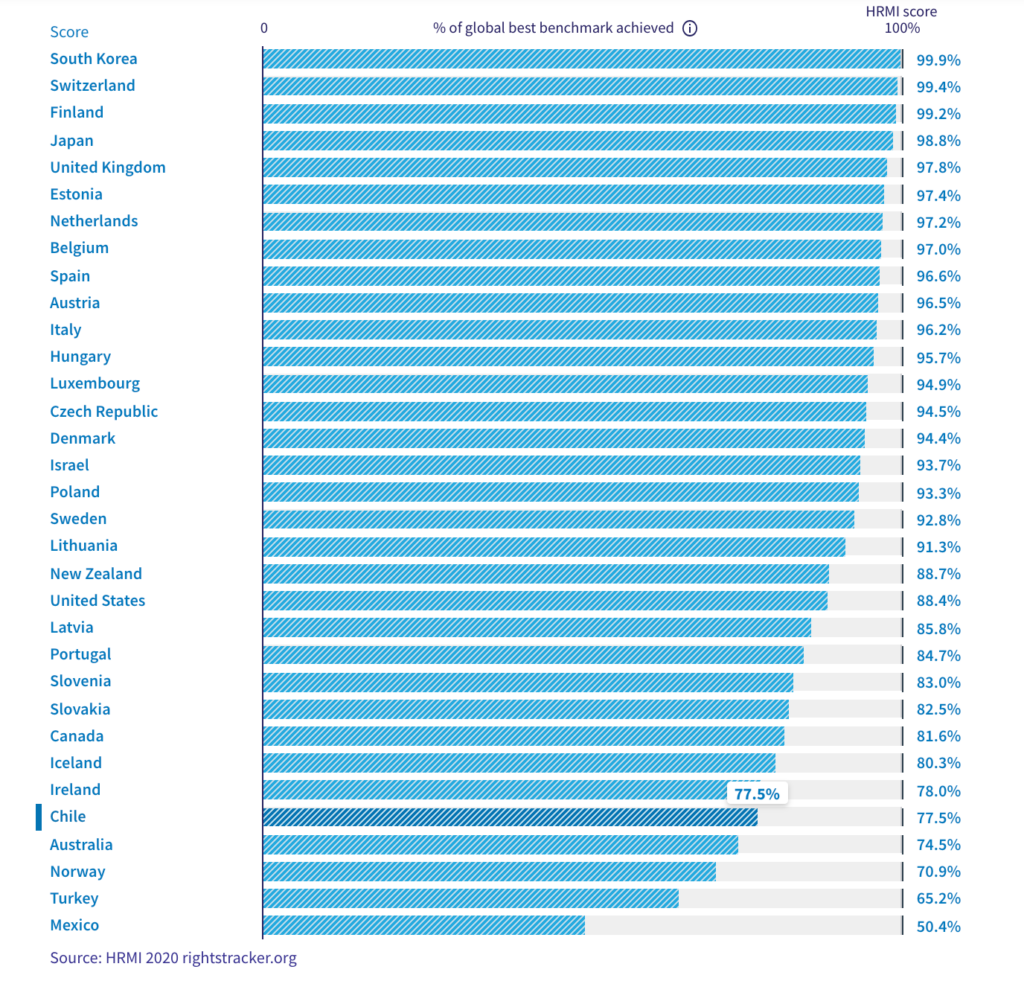

Below we can see how Chile’s right to housing performance compares to the rest of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) members, using the global best benchmark. Using this benchmark, HRMI data shows that when Chile’s resources are compared on a global scale, it ranks at number 11 out of the 26 OECD countries with data, which suggests that while it is performing better than countries like the United States, it still has more to do to catch up to other better performing countries like Estonia, the Czech Republic and Italy:

Continuing to look at Chile’s performance among OECD countries using the global best benchmark and this time looking at affordable housing scores, Chile’s ranks at number 10 out of the 26 OECD countries with data:

However, we get a different picture when assessing Chile’s performance on safely managed sanitation among OECD countries using a global best benchmark. Chile ranks 27 out of the 33 OECD countries with data. It still has a very long way to go.

What can Chile do next?

Chile has performed generally well on many of the broad indicators for the right to housing HRMI uses, but there remain further aspects of the right to housing that need to be addressed. Here is a short list of issues Chile could further explore and address:

- What other indicators, not monitored by HRMI, can help to tell a richer story about the right to housing in Chile? These indicators could encompass other aspects of housing such as legal security of tenure, nearness to employment or school, or cultural acceptability of tenants into their communities, especially if they are migrants.

- Which groups of people are most likely to be denied their right to housing in Chile? This is a question that HRMI can begin to answer when it expands its qualitative human rights research to Chile, in the future. In the meantime, TECHO is in the process of reporting on the housing situation of immigrants in Chile who are living in slums.

- To what extent are people living in informal settlements enjoying their right to housing? As noted above, TECHO has developed a national census report (only available in Spanish) that surveys the lived experiences of people living in slums. They find that in 2020, more than 80,000 families (a 70% increase from 2019) are now living in informal settlements, the vast majority of which have only irregular access to reliable electricity, potable water, and sanitary sewage systems.

- Are there significant and persistent differences between cities and rural areas? And what can Chile do to ensure that the right to housing is enjoyed regardless of geography?

- It is evident that Chile ranks well when compared to its neighbours in the Americas. What housing policy insights can be exported to the rest of the countries in the region, so that they too can lift their performance?

Thanks for your interest in HRMI. To further explore our human rights data for Chile, please visit our Rights Tracker, where you can find data by country or right.

We are grateful to our friends at The Center for Social Research from TECHO-Chile and Fundación Vivienda for their collaboration on this article.