United Kingdom: human rights during the pandemic

The Human Rights Measurement Initiative (HRMI, pronounced ‘her-mee’) is the first global project to track the human rights performance of countries. Its 2021 Human Rights Rights Tracker gives human rights scores on up to 13 different human rights contained in United Nations treaties, for around 200 countries.

2020 was an extremely difficult year for the United Kingdom, which was very hard hit by Covid-19. HRMI’s new human rights scores reflect the extra challenges, and highlight groups of people who were particularly vulnerable to violations.

The 2021 Rights Tracker scores for the United Kingdom include many positive scores, but also some strikingly poor results, particularly in terms of who is most at risk of rights abuses.

Headlines (further details below):

- Government responses to the Covid-19 pandemic had overwhelming impact on human rights

- Single parent families experience rights violations

- Widespread violations of economic and social rights in the UK

- Scores highlight the need for racial justice

- Disabled people suffer high levels of human rights violations

- Experts highlight threats to the rights of children

The civil and political rights data, and the people at risk responses, were collected in February and March 2021, about events in the year 2020.

The economic and social rights data are based on figures from international databases, taking into account GDP per capita, and provide scores for every year from 2007-2018.

New human rights scores for the United Kingdom

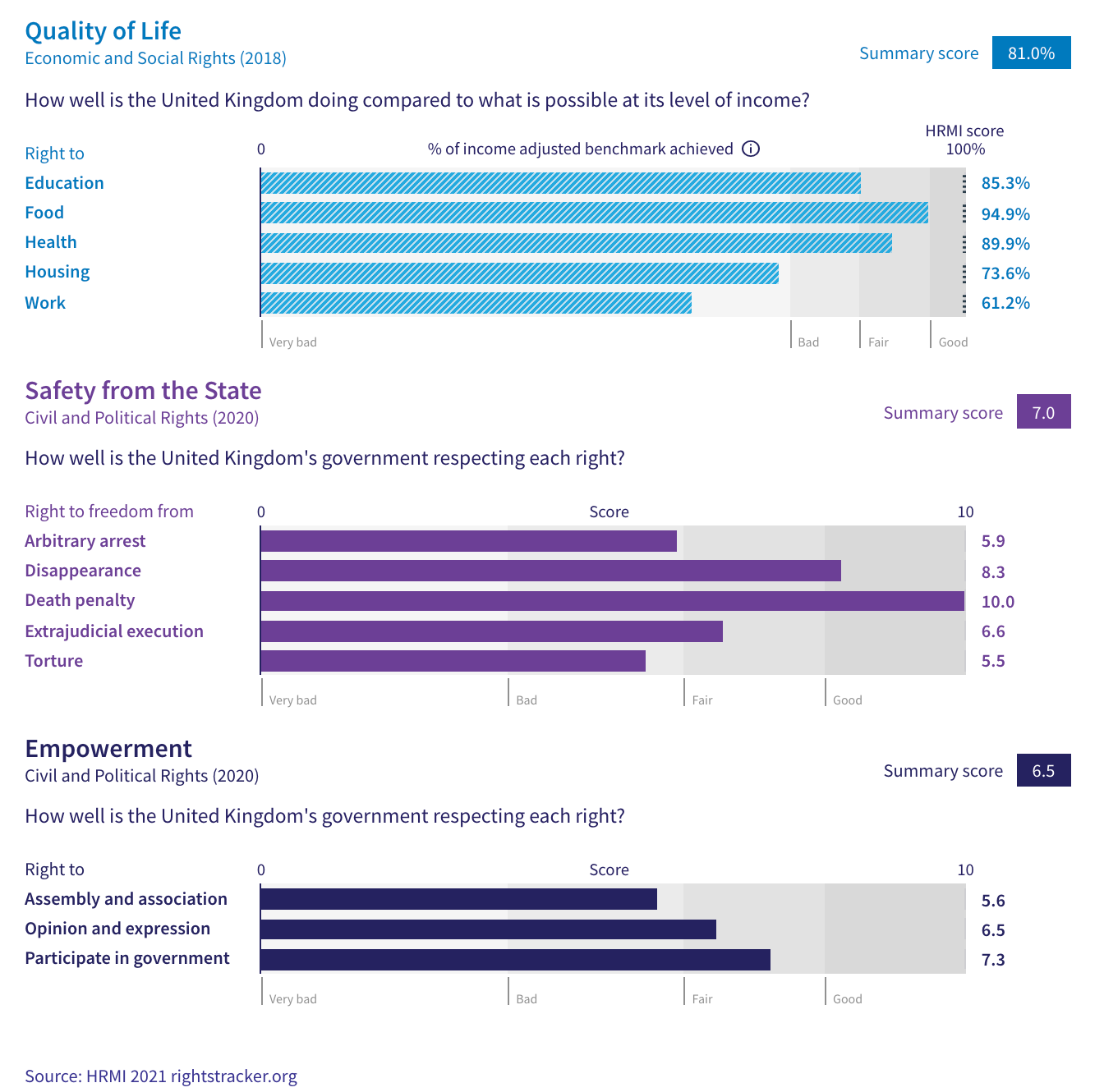

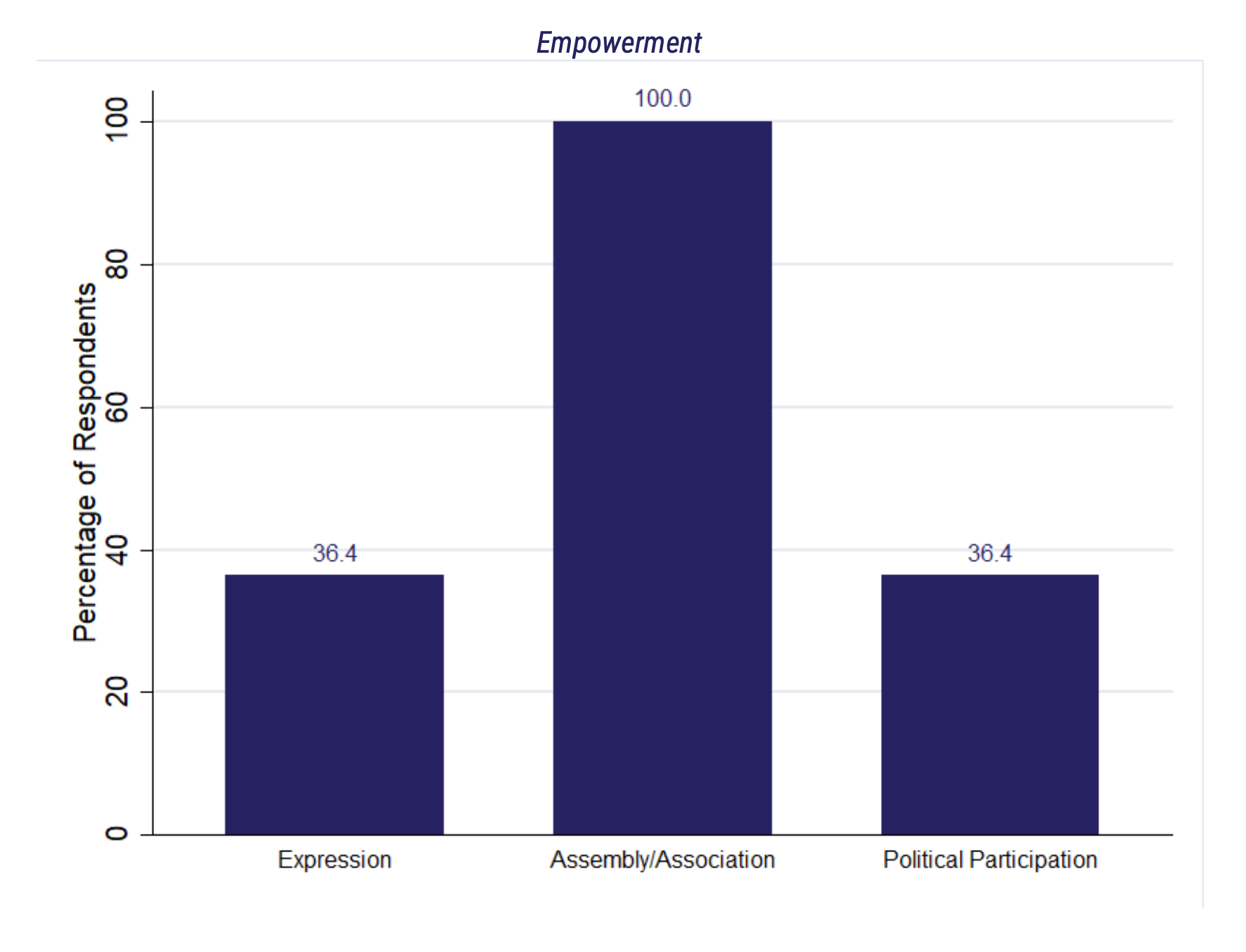

Empowerment: 6.5 out of 10

The United Kingdom scored 6.5 out of 10 for Empowerment rights, which measure:

- the right to assembly and association

- the right to opinion and expression

- the right to participate in government

The United Kingdom’s Empowerment score of 6.5, based on a detailed survey of human rights experts, tells us that a significant number people in the United Kingdom are not enjoying their civil rights and political freedoms. More detail below.

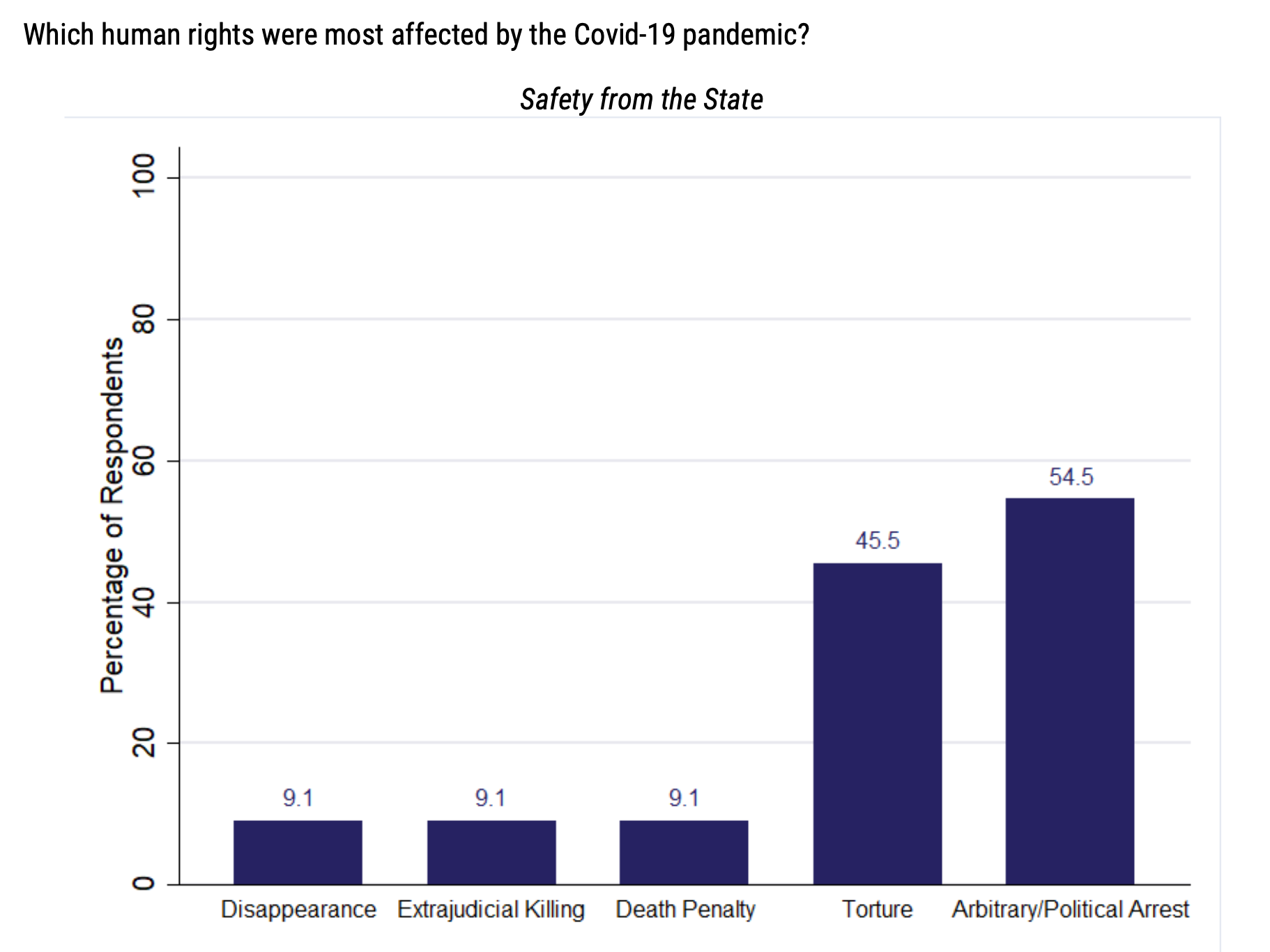

Safety from the State: 7 out of 10

The United Kingdom scored 7 out of 10 for Safety from the State rights, which measure:

- freedom from torture

- freedom from execution by death penalty

- freedom from extrajudicial execution

- freedom from disappearance

- freedom from arbitrary or political arrest and detention

The United Kingdom’s Safety from the State score of 7 out of 10, based on a detailed survey of human rights experts, suggests that while most people are safe from arbitrary arrest, torture, disappearance, execution or extrajudicial killing, some are not. More detail below.

Quality of Life: 81%

The Quality of Life score is a measure of how well a country uses its wealth to ensure people’s rights to food, education, health, housing and work are met. The score is produced by using data from international databases, and measuring outcomes against a country’s income level.

The United Kingdom’s income adjusted Quality of Life score of 81% implies that with the resources it has, the United Kingdom can do much more than it currently is to ensure its people enjoy their economic and social rights. As such, it has some way to go to meet its immediate obligations under the international treaties it has signed.

HRMI co-founder and Economic and Social Rights Lead Dr Susan Randolph explains further, ‘The United Kingdom’s Quality of Life score is 81%, measured against what should be possible given its current resources. Among the five economic and social rights we consider, its greatest deficit is in ensuring all have access to affordable housing, and access to work that provides a decent standard of living. The UK’s score on the right to work is only 61.2%, falling in the ‘very bad’ range.’

Human rights in the United Kingdom: themes from the data

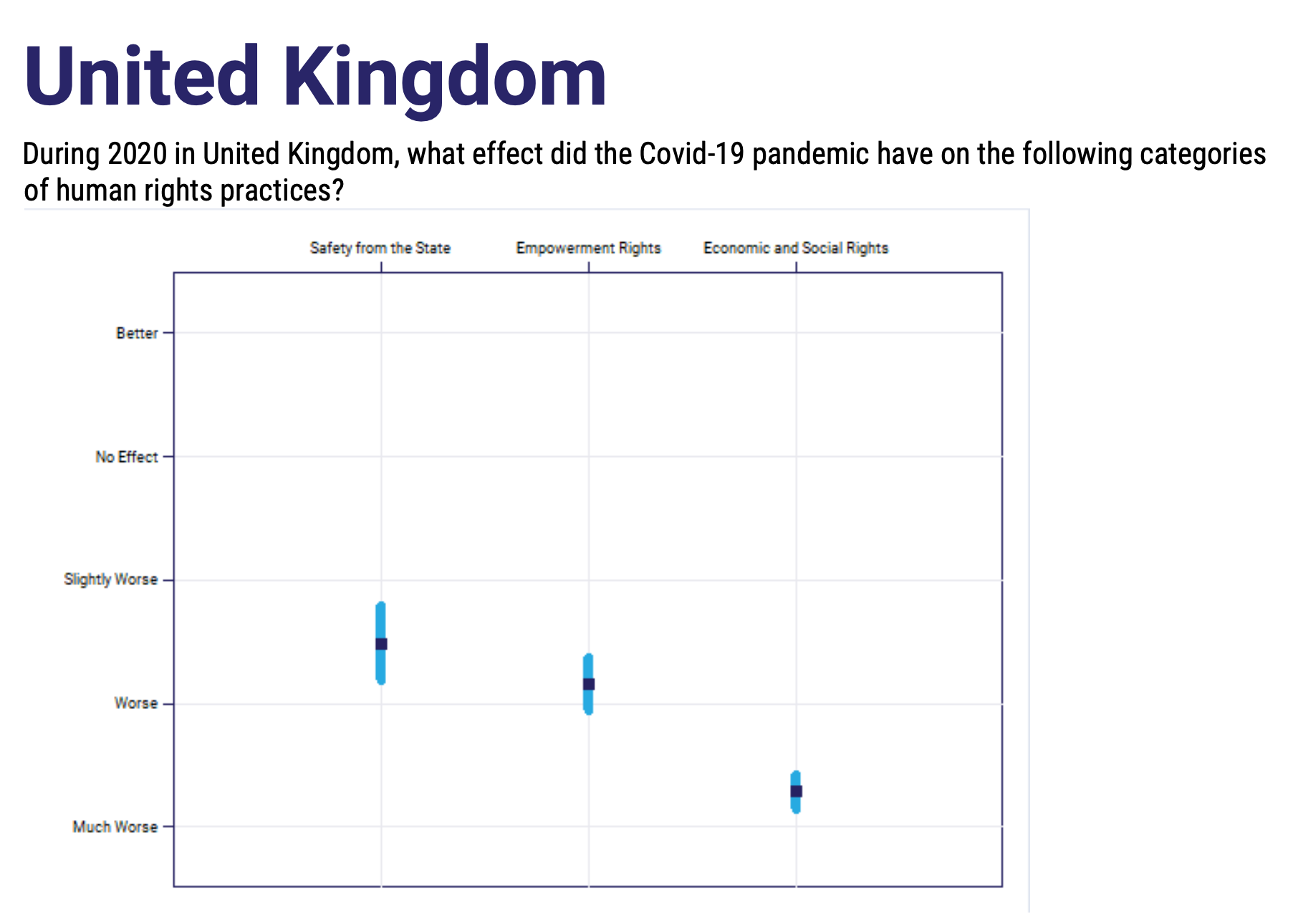

Government responses to the Covid-19 pandemic had overwhelming impact on human rights

We asked human rights experts about the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on people’s human rights. For every right, respondents said things were worse because of the pandemic.

Economic and social rights were most badly affected, due to job losses, economic recession, austerity measures, and the enormous burden on the health system. Children’s rights to both food and education were impacted by school closures.

For more detail, see below, and our full report, Human Rights During the Pandemic, and the ‘people at risk‘ tab of the United Kingdom Rights Tracker page (click ‘show more’ under each word cloud).

When asked how Covid-19 had affected human rights in the UK, respondents gave these answers, on average:

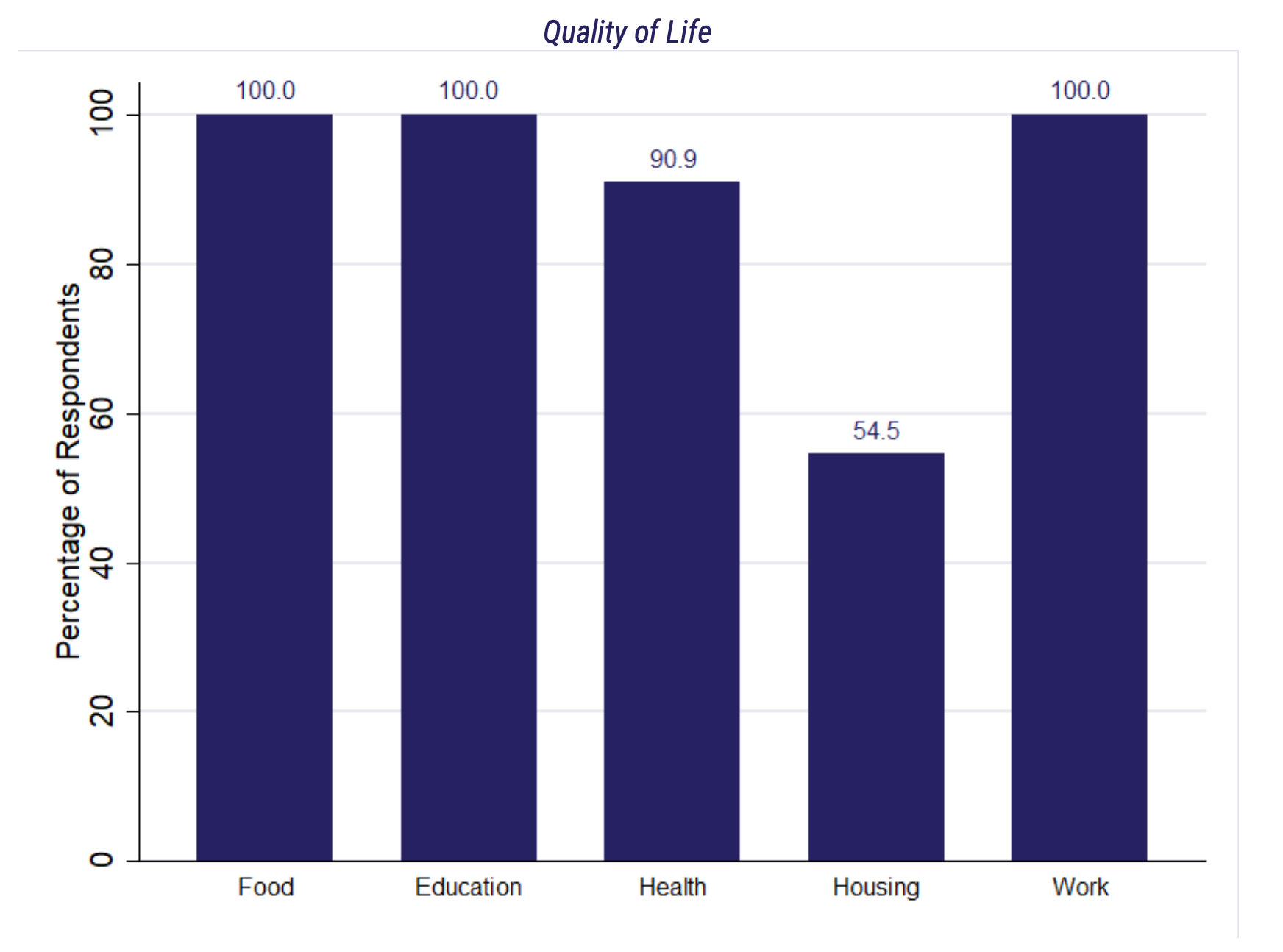

People were then asked which of the 13 human rights we measure were affected by the pandemic. Here are the results:

Human rights experts in the UK made extensive comments about who was at risk of rights violations because of the pandemic, including the following reports, which are all available on the Rights Tracker, under each ‘people at risk’ word cloud.

Right to education:

- Students, as schools closed because of Covid-19, particularly students with low social or economic status who had less access to private or online support, digital technologies, a quiet place to study, and the regular testing employed by private educational establishments

- People in particular geographic locations, particularly those living in areas where internet was not as widely available or those living in certain Scottish local authorities where tablets and data were not provided for children who did not have them

- People whose main language is not English due to the reduction of face-to-face English for Speakers of Other Languages instruction

- Children with disabilities, who struggled due to the shift to digital learning and who face disproportionately high rates of exclusion, lack of inclusive relationships, sexual health and parenthood education

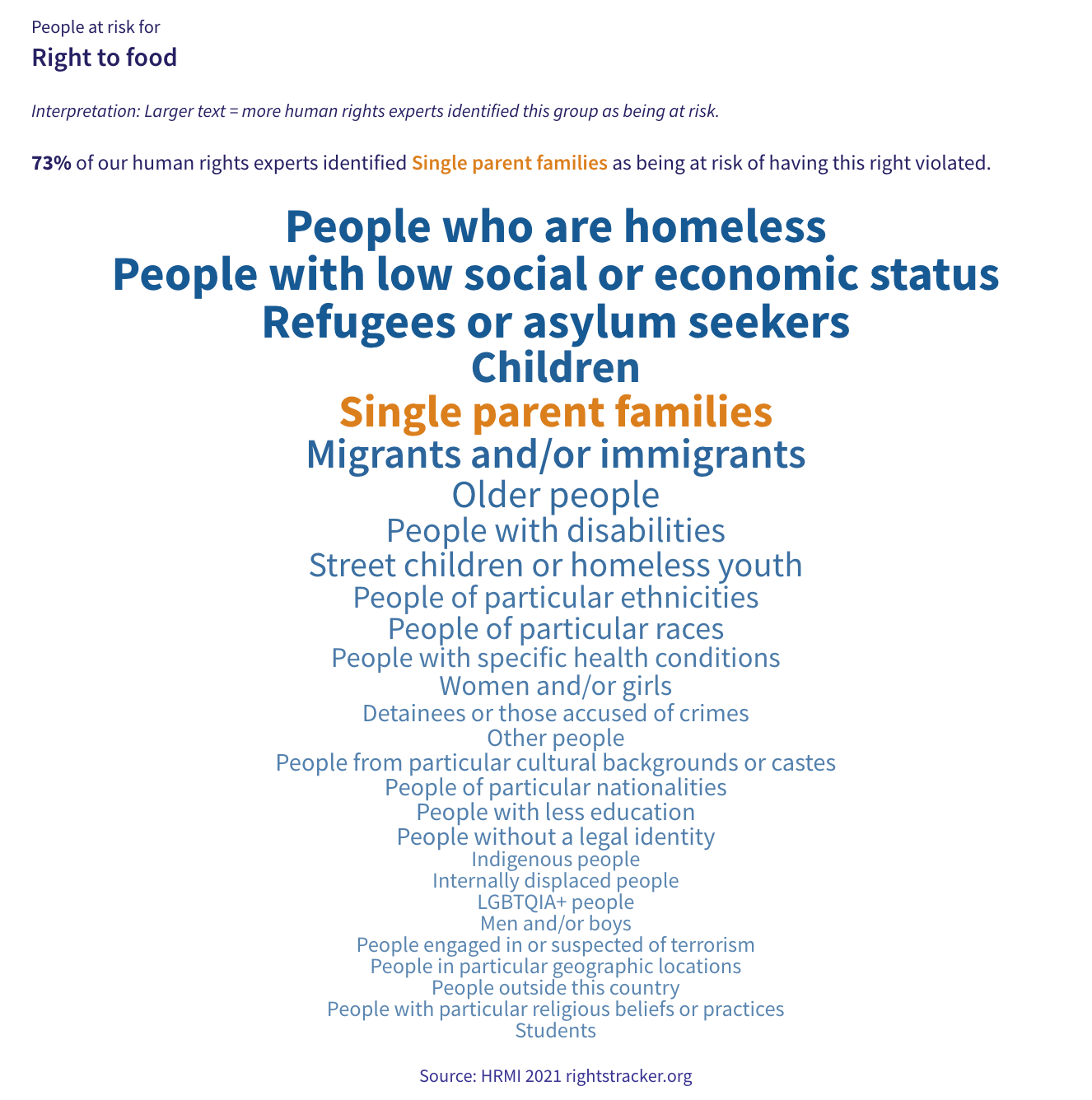

Right to food:

- Children, as distribution of school meals once schools closed was not consistent across Scotland, with some local authorities providing vouchers while others had meals at collection points that not all people could easily reach

- People with low or economic status who lost their jobs because of Covid-19

- All people were at risk due to the government’s increasing implementation of austerity measures, which has resulted in limited social security

- Families with children, particularly single parent families or families with a disabled member, who increasingly relied on food banks

- Immigrants and asylum seekers who did not have access to public funds and who received substandard food due to the government subcontracting to people they had personal relationships with

- People isolating because of Covid-19, particularly older people, who did not have access to internet or anyone to shop for them

Right to freedom from arbitrary arrest and detention:

- Young people and children, especially as the definition of child was not clear in Covid-19 legislation and, in Scotland, some 16 and 17-year-olds were treated as adults for violating Covid-19 lockdowns

- People believed to be violating Covid-19 guidelines, especially as police enforcement was often excessive, disproportionate, and even outside the scope of the law as many police officers used the phrase ‘the spirit of the law’ to detain people, though this term has no legal basis

- Black boys and men as Covid-19 laws increased interaction between them and the police and many of these interactions led to arrest

Please see the Rights Tracker for more comments from UK experts.

Single parent families experience rights violations

For the first time in 2021, HRMI included ‘single parent families’ as an option for respondents to choose. Human rights experts in United Kingdom said that single parent families were at particular risk of rights violations with respect to:

- right to education

- right to food

- right to health

- right to housing

- right to work

- right to freedom from arbitrary arrest and detention

- right to freedom of opinion and expression

- right to participate in government.

For example, here is the word cloud for the right to food:

Widespread violations of economic and social rights in the UK

For all five Quality of Life rights we measured, the UK has some way to go to meet its human rights obligations. It is also concerning that our expert respondents provided long lists of people who were especially at risk of not enjoying these rights.

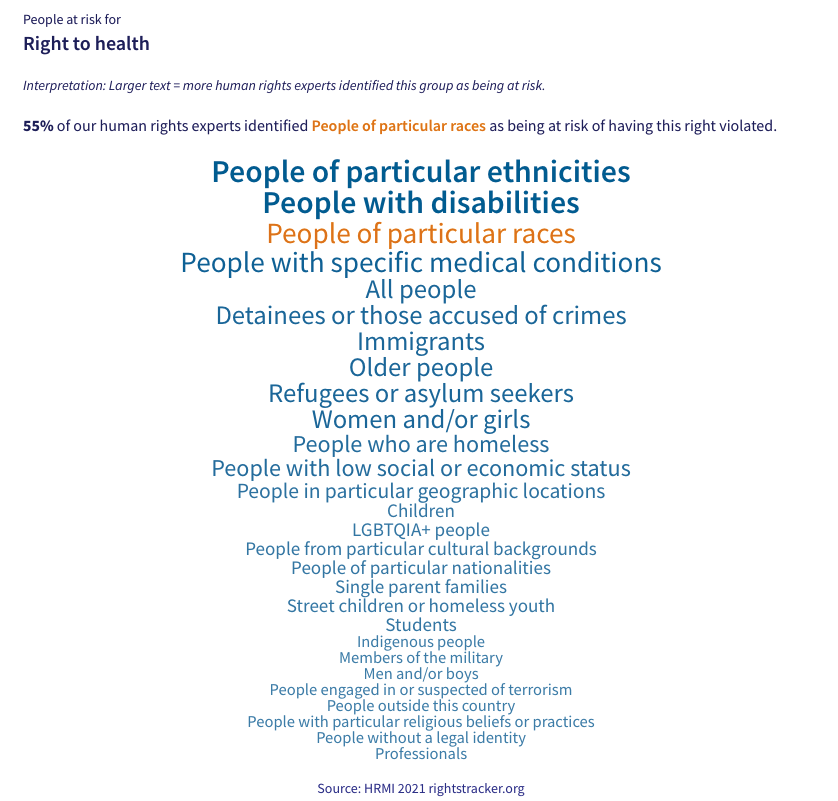

Scores highlight the need for racial justice

For nearly all the human rights we measure, experts identified race as a factor.

Disabled people suffer high levels of human rights violations

Our human rights experts identified disabled people as being at particular risk of violations of most of the rights we measure, particularly:

- the right to freedom from torture

- the right to education

- the right to food

- the right to housing

- the right to health

- the right to have work

- the right to opinion and expression

- the right to participate in government.

Disabled people were also badly affected by Covid-19 restrictions, having trouble with access to food, and other services, and to participate in government.

Experts highlight threats to the rights of children

Children were identified as being particularly vulnerable to abuses of these rights:

- the right to freedom from torture

- the right to food

- the right to education

- the right to housing

- the right to health.

About the Human Rights Measurement Initiative

‘Our vision is a world where countries are competing to see who can treat people the best.’

— Anne-Marie Brook

HRMI is a global, not-for-profit human rights data platform that aims to improve people’s lives by producing user-friendly, reliable information on the human rights progress of countries.

HRMI is filling a gap in human rights data, providing human rights practitioners with powerful tools to show governments how they are performing, and remind them of the promises they’ve made by signing human rights treaties.

Co-founder and Development Lead Anne-Marie Brook, an economist and social entrepreneur, based in Wellington, New Zealand, says, ‘We know that it is hard for countries to make progress if good data aren’t available that show how they’re actually doing. HRMI is filling a gap in human rights data, providing human rights practitioners with powerful tools to show governments how they are performing, and remind them of the promises they’ve made by signing human rights treaties.’

How HRMI produces the scores

HRMI human rights scores are produced by two teams of researchers.

Co-founder and Economic and Social Rights Lead Dr Susan Randolph produces scores for up to five Quality of Life rights, for around 200 countries, using indicator data supplied by countries to international databases. Dr Randolph then analyses the data using the award-winning SERF Index she developed with her colleagues, Sakiko Fukuda-Parr and Terra Lawson-Remer.

‘The SERF Index is unique because it takes into account a country’s financial resources,’ Dr Randolph explains. ‘The income-adjusted score shows how close a country is to meeting its urgent duty, compared with other countries with similar resources – for these rights, the realistic target is 100%.’

‘The HRMI Country Report tells people whether their government is doing its best with the country’s resources to give full effect to their economic and social rights, or whether there is room for improvement.’

You can watch this short animated video for a further explanation of how we create the scores:

Co-Founder and Civil and Political Rights Lead, Dr K Chad Clay from the University of Georgia, in the United States, heads up the data collection and analysis for HRMI’s Empowerment and Safety from the State measurements.

These rights are politically sensitive to measure, and HRMI is the first global project to track them systematically, country by country. In 2021 HRMI produced data for 39 countries, and is ready to expand to the rest of the world once sufficient funding is secured.

‘We know that the best sources of information on human rights in a country are the people directly monitoring conditions in that country. So we designed a detailed expert survey to be filled out by human rights practitioners, like lawyers, journalists, and advocates, including people working for organisations like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch. We collected data in February and March of 2021, asking about the situation in their country in 2020 and 2019. We then used statistical techniques to be sure we were providing the most accurate and honest information possible. Now we’re presenting our findings in scores out of ten for each of the eight civil and political rights we measure.’

You can watch this short animated video for a further explanation of how we create the civil and political rights scores:

HRMI works on an annual cycle and is already preparing to collect data about 2021, ready for publication in 2022. As funding increases, HRMI is ready to:

- expand to cover more countries

- measure performance on more rights, and

- provide more detail on performance, such as separating out scores by sex and race.

Thanks for your interest in HRMI. To further explore our human rights data for the UK, please visit our multilingual Rights Tracker, where you can find data by country or right.