Kazakhstan: progress needed to fulfil President’s human rights promise

The Human Rights Measurement Initiative (HRMI) is the first global initiative to track the human rights performances of countries. This case study focuses on the economics and social rights outcomes for Kazakhstan, and can be treated as a press release for media. All data discussed below are available on our Rights Tracker. See also HRMI’s Research credentials. This country spotlight refers to data published in 2019.

A president’s promise

In 2019, Kazakhstan’s newly inaugurated president, Kassym-Jomart Tokaev committed to ‘protect the rights of every citizen.’

Citing his promises, Human Rights Watch penned an open letter to Tokaev, raising several key areas of concern that he must address in order to fulfil this goal. These included:

- election interference

- restrictions on freedom of assembly, and

- restrictions on free speech — including excessively broad criminal laws used against civil society.

HRMI’s human rights scores for Kazakhstan confirm that these are still areas of real concern, as many citizens are not enjoying their fundamental human rights.

What do HRMI’s data show?

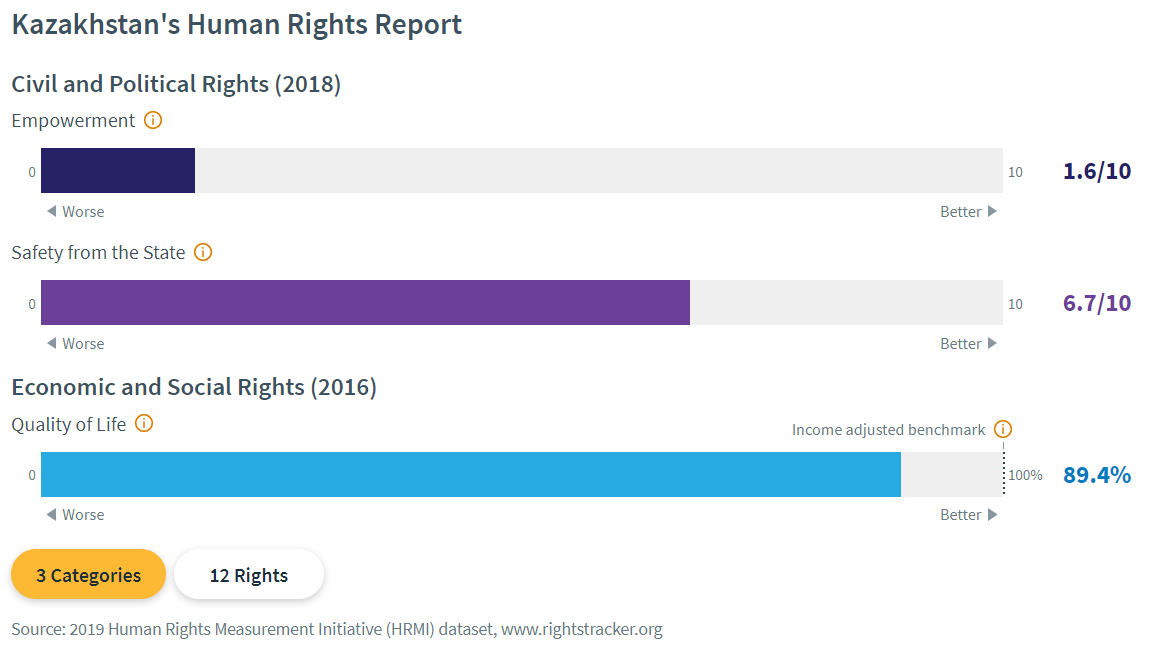

Below is an overview of HRMI’s human rights report for Kazakhstan, as seen on our Rights Tracker:

Kazakhstan scored poorly for civil and political rights, with a very low 1.6/10 for empowerment rights, and 6.7/10 for safety from the state.

There is an urgent need for Tokaev to fulfil his promise by drastically improving respect for civil and political rights in Kazakhstan, particularly empowerment rights. These include the rights to assembly and association, opinion and expression, and participation in government.

At 89.4%, Kazakhstan also has much room to improve in quality of life rights. These are the rights to health, housing, food, work, and education.

Civil and political rights

Empowerment rights

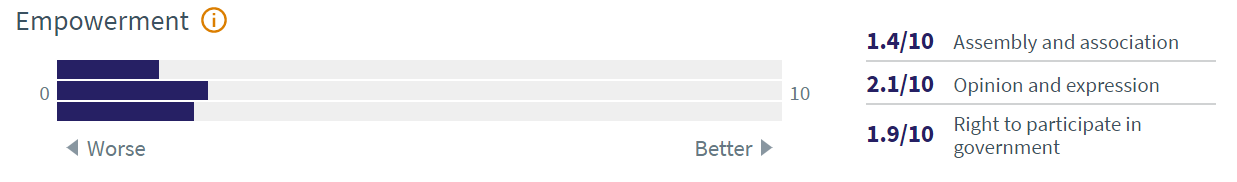

Kazakhstan’s combined empowerment score of 1.6/10, shown above, suggests that a large number of people are not enjoying their civil liberties and political freedoms.

The individual scores for freedom of speech, assembly and association, and the right to participate in government are shown in the graph below:

Kazakhstan needs to make major improvements in all three areas.

Right to assembly and association

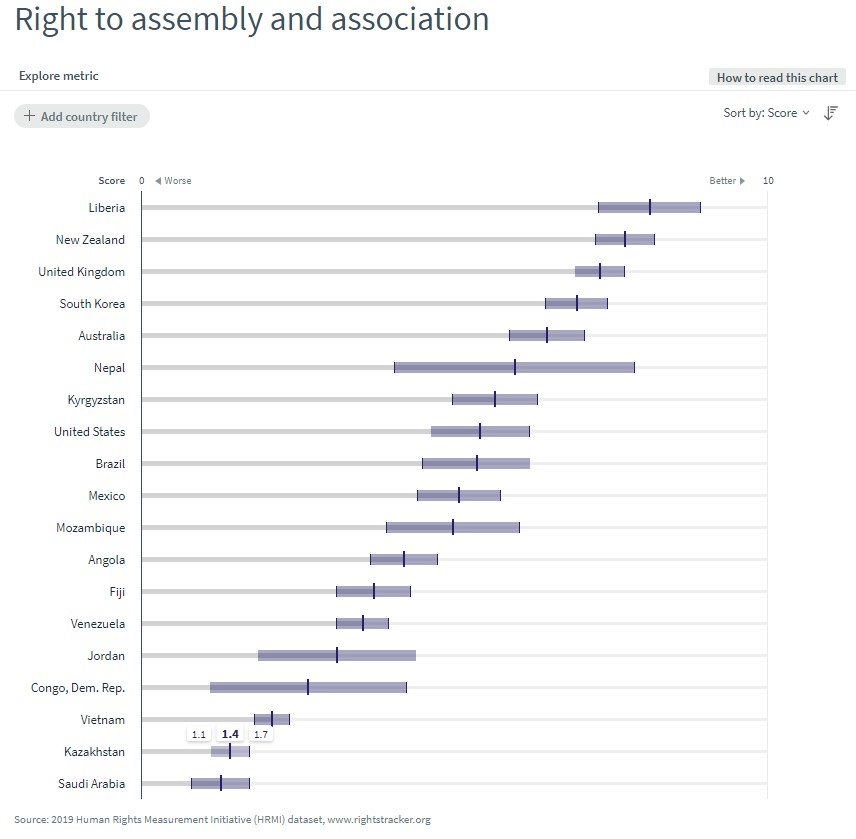

Kazakhstan scored 1.4/10 for the right to assembly and association, as shown in the graph above.

The graph below compares Kazakhstan’s score with the scores of 18 other countries from around the world.

The right to assembly and association scores are presented here with uncertainty bands, showing the credible range of scores, similar to the ‘margin of error’ in opinion polls. Because the uncertainty bands for Kazakhstan and Saudi Arabia overlap, Kazakhstan could in fact be performing worse than Saudi Arabia for the right to assembly and association.

What’s certain is that Kazakhstan is performing among the very worst of the 19 countries HRMI collected assembly and association data for in 2019.

We asked our expert survey respondents which groups of people they thought were at risk of having their right to assembly and association violated.

The following word cloud represents their answers.

Note: The bigger the text, the greater the number of human rights experts who identified that group as at risk.

This word cloud shows that 59% of our human rights experts thought that everyone in Kazakhstan is at real risk of having their right to assembly and association violated.

Additionally, 59% of experts identified the following groups as at risk:

- human rights advocates

- people who protest or engage in non-violent political activity, and

- people with particular political affiliations or beliefs.

Journalists and members of labour unions were identified by 47% of experts.

This is in line with Human Rights Watch‘s finding that ‘Kazakh authorities routinely deny permits for peaceful protests against government policies. Police break up even single-person unauthorized protests, and arbitrarily detain organizers and participants,’ and that ‘[i]n recent years there has been a concerted government crackdown on the independent trade union movement in Kazakhstan.’

Right to opinion and expression

Kazakhstan scores 2.1/10 for the right to opinion and expression.

Experts identified many groups as being at risk of having this right violated:

These responses show that human rights activists are at a particular risk of having their right to free speech violated. Additionally, 71% of experts identified journalists and people with particular political affiliations or beliefs as being at risk of having this right violated, while 65% identified people who protest or engage in non-violent political activity as being at risk.

In total, there were 31 groups of people identified by human rights experts as being at risk of having their right to opinion and expression violated.

All people were identified as being at risk by 47% of experts.

Reporters Without Borders ranked Kazakhstan 158th in the world out of 180 nations in its World Press Freedom Index. In explaining the score, Reporters Without Borders raised concerns about the banning of opposition newspapers in 2013, and the targeting of newspapers that express even a small amount of criticism of the government. Accordingly, they wrote, ‘[i]t is high time to dispense with this heritage of censorship.’

Other groups most commonly identified by our experts as at risk of having their right to opinion and expression violated are:

- Members of labour unions (59%)

- Detainees or those accused of crimes (47%)

- People engaged in, or suspected of terrorism (47%)

- People with particular religious beliefs or practices (47%)

- LGBTQIA+ people (35%)

- People engaged in or suspected of political violence (35%)

This confirms that there are substantial restrictions on the ability of citizens to freely disseminate and access information.

Right to participate in government

Kazakhstan scores 1.9/10 for the right to participate in government.

Our experts identified the following people as at risk of having their right to participate in government violated:

People with particular political affiliations or beliefs were identified by 59% of experts as being at risk.

Notably, 47% of our experts said that all people are at risk of having their right to participate in government violated.

Other specific affected groups include people who protest or engage in non-violent political activity, human rights advocates, and detainees or those accused of crimes.

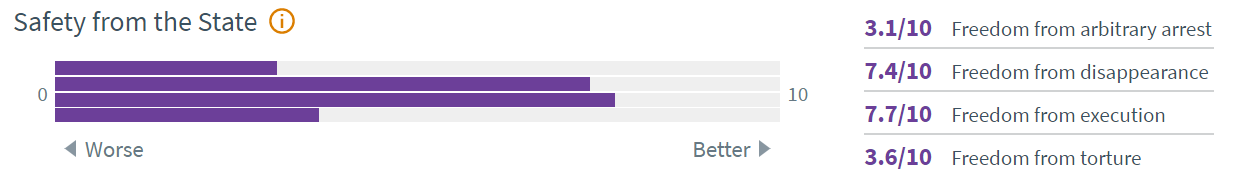

Safety from the state

HRMI’s ‘safety from the state’ category is for physical integrity rights.

Kazakhstan’s safety from the state score of 6.7/10 suggests that a significant number of people are not safe from one or more of the following: arbitrary arrest, torture, disappearance, execution or extrajudicial killing. Execution and extrajudicial killing are both included in HRMI’s ‘freedom from execution’ score.

The individual scores of these rights are as follows:

Although Kazakhstan scores higher here than for empowerment rights, these clearly indicate that Kazakhstan needs to improve respect for all four of these physical integrity rights.

Freedom from arbitrary arrest and freedom from torture both scored particularly poorly, at 3.1/10 and 3.6/10 respectively.

Many groups were identified by a large percentage of experts as being at risk of arbitrary arrest:

People who protest or engage in non-violent political activity were identified by 78% of experts as at risk of being arbitrarily arrested. Similarly, 72% of experts identified human rights activists and people with particular political affiliations or beliefs. Journalists were also identified by 67% of experts.

Quality of Life rights

Quality of life rights are economic and social rights including the rights to food, health, education, housing, and work.

HRMI produces two quality of life scores for each country, each score measuring against a different benchmark.

The global best benchmark scores all countries against the same high standard.

By adjusting for a country’s income, HRMI also scores countries against the level they could be expected to be performing at, given their income level. This is the income adjusted benchmark.

The income adjusted benchmark is a ground-breaking tool which uses the SERF Index methodology, developed by HRMI co-founder Susan Randolph and her colleagues Sakiko Fukuda-Parr and Terra Lawson-Remer. It best measures how well countries are upholding their obligations under international law because under Article 2 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), each country is obligated to progressively achieve economic and social rights “to the maximum of its available resources.”

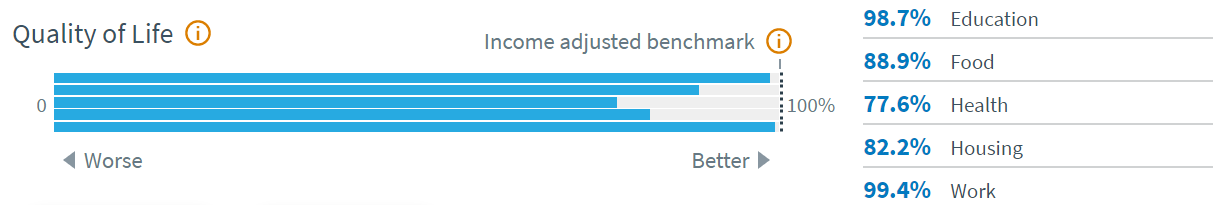

In the graph below, the income adjusted benchmark has been selected.

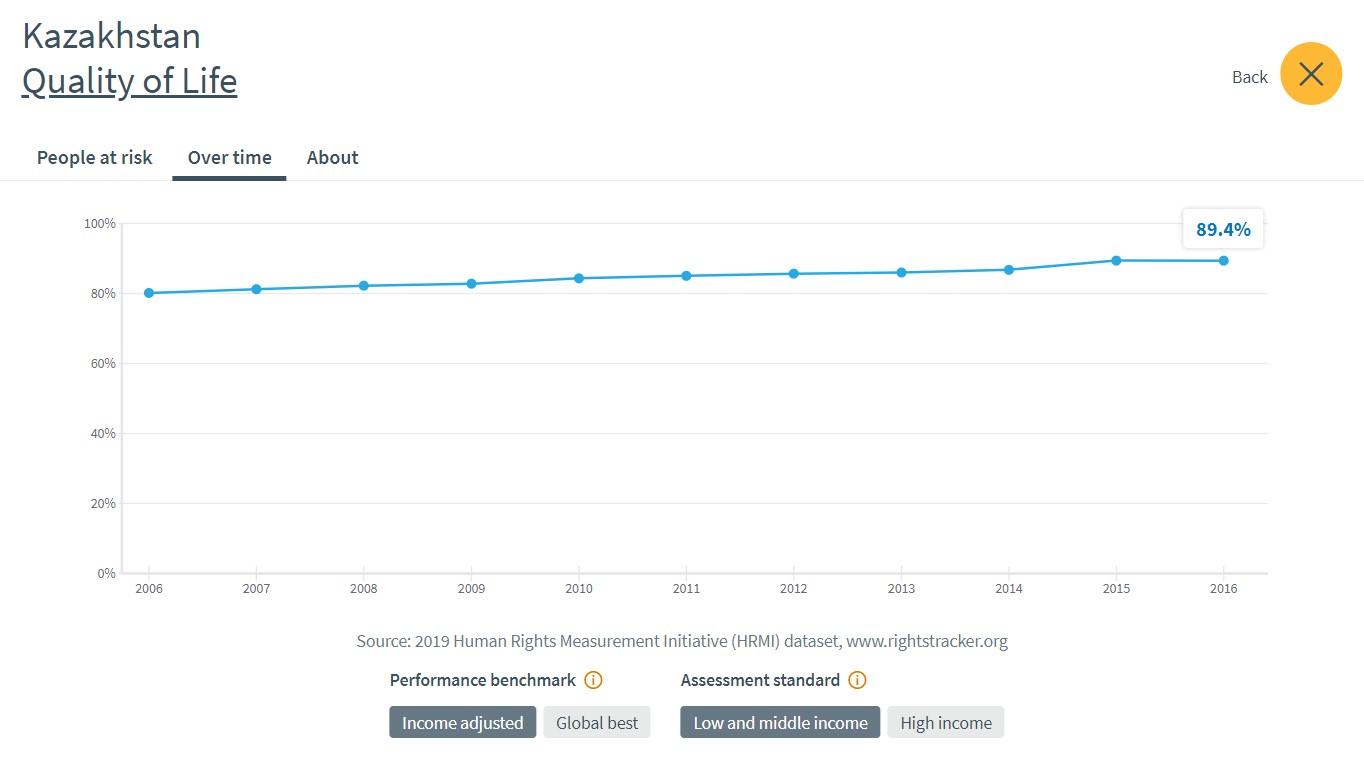

Kazakhstan scores 89.4% on quality of life when scored against the ‘income adjusted’ benchmark.

This score takes into account Kazakhstan’s resources and how well it is using them to make sure its people’s quality of life rights are fulfilled.

This score tells us that Kazakhstan is only doing 89.4% of what should be possible right now with the resources it has. Since anything less than 100% indicates that a country is not meeting its current duty under international human rights law, our assessment is that Kazakhstan has some way to go to meet its immediate economic and social rights duty.

Kazakhstan’s lowest quality of life score is for the right to health, at 77.6%.

The good news is that Kazakhstan has been increasing its quality of life score since at least 2006, as show by the graph below.

The design of the SERF Index methodology means HRMI’s data allow the comparison of countries’ scores. You can compare Kazakhstan’s economic and social rights scores to those of other countries, including for the right to education, the right to food, the right to health, the right to housing, and the right to work.

When asked to provide more context about who was least likely enjoy their economic and social rights in 2018, our respondents mentioned all of the following:

- All people are at risk of experiencing some difficulty in enjoying their economic and social rights

- Girls wearing hijab may not be allowed in schools

- People who are unemployed and pensioners on a minimum wage pension may lack access to adequate food

- People on particular religious or limited diets, e.g. people who keep Kosher or who maintain a vegan diet, may find it difficult to obtain adequate food

- People in prison often lack access to adequate healthcare, alongside many other economic and social rights

- Large families, students, and young people face difficulty in securing housing

- Young people under 25, women over 45, and men over 50 may have difficulty obtaining employment

- A near complete lack of independent trade unions

- People living in rural regions or regions of ecological disaster

- Public sector workers

- Journalists

- Trade unionists

- Civil society activists

- People with disabilities

- People suffering chronic diseases

- The entire population

- People who are homeless

- Children

- People with low socio economic status

- People with low income

- Lawyers

- People formerly in prison

- Human rights activists

- Migrants

See our Rights Tracker for more information on who was identified as being at risk for each quality of life right.

Summary of Kazakhstan’s human rights performance

Our data show that Kazakhstan has a long way to go before its people can have full enjoyment of their civil and political rights.

Several groups of people were consistently identified by high numbers of our experts as being at risk of having these rights violated, including:

- people with particular political affiliations or beliefs

- people who protest or engage in nonviolent political activity

- human rights advocates

- journalists

Furthermore, all people were frequently identified as being at risk.

Our data also show that Kazakhstan is not meeting its quality of life rights obligations under international law, and is doing particularly poorly on the rights to health and housing. These are the same rights that Kazakhstan’s neighbour Kyrgyzstan scores lowest for.

Although Kazakhstan has much lower civil and political rights scores than Kyrgyzstan, they score the same on quality of life rights.

It is clear that there is much work ahead for President Tokaev if he is to keep his promise of protecting the rights of all citizens of Kazakhstan; a promise which urgently needs to come to fruition.

Thanks for your interest in HRMI. To further explore our human rights data for Kazakhstan, please visit our Rights Tracker, where you can find data by country or right.