Jordan: 2020 human rights scores show challenges and successes

Measuring Human Rights in Jordan

The Human Rights Measurement Initiative (HRMI, pronounced ‘her-mee’) is the first global project to track the human rights performance of countries. HRMI has produced human rights scores on 13 different human rights contained in United Nations treaties, publishing all data on our Rights Tracker.

The 2020 evaluation of Jordan contains an overall positive score for quality of life, but also some strikingly poor results, particularly in terms of how the government respects its citizens’ civil liberties and political freedoms. Of 13 rights measured, Jordan’s scores only put it in the top ‘good’ category for 3 rights.

Headlines

- Refugees, asylum seekers, and immigrants suffer high levels of human rights violations

- Encouraging scores for quality of life rights

- Detainees or those accused of crimes lack safety from the state

- Journalists’ freedom of association at risk

- Worryingly low levels of political empowerment in Jordan

- Experts highlight threats to the rights of children and young people

The civil and political rights data, and the people at risk responses, were collected as the Covid-19 pandemic was beginning to sweep the world.

The economic and social rights data are based on figures from international databases and score every year 2007-2017.

Summary of Jordan’s Scores

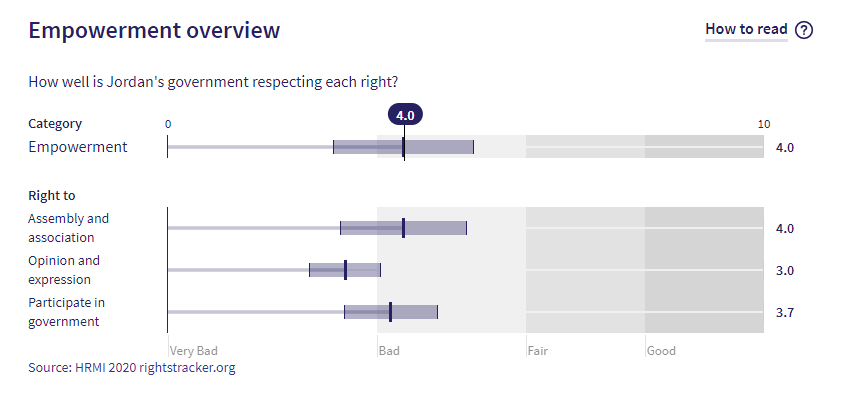

Empowerment: 4.0 out of 10

Jordan scored 4.0 out of 10 for Empowerment rights, which measure:

- the right to participate in government

- the right to opinion and expression

- the right to assembly and association

Jordan’s Empowerment score of 4.0, based on a detailed survey of human rights experts, tells us that a significant number people in Jordan are not enjoying their civil rights and political freedoms. Jordan is performing worse than a significant number of countries in our sample since 2017.

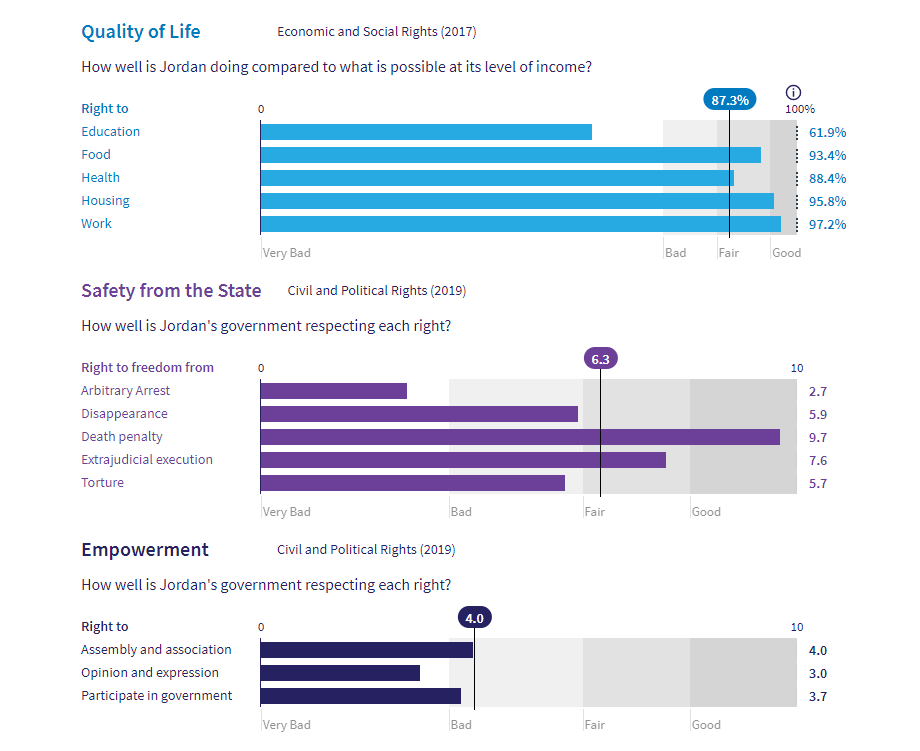

Safety from the State: 6.3 out of 10

Jordan scored 6.3 out of 10 for Safety from the State rights, which measure:

- freedom from torture

- freedom from execution

- freedom from extrajudicial killing

- freedom from disappearance

- freedom from arbitrary or political arrest and detention

Jordan’s Safety from the State score of 6.3, based on a detailed survey of human rights experts, suggests that a while most people are safe from arbitrary arrest, torture, disappearance, execution or extrajudicial killing, some are not.

Quality of Life: 87.3%

The Quality of Life score is a measure of how well a country uses its wealth to ensure people’s rights to food, education, health, housing and work are met. The score is produced by using data from international databases, and measuring outcomes against a country’s income level.

HRMI co-founder and Economic and Social Rights Lead Dr Susan Randolph explains that, ‘Jordan’s income adjusted Quality of Life score of 87.3% implies that with the resources it has, Jordan can do more than it currently is to ensure its people enjoy their economic and social rights. As such, it has a long way to go to meet its obligations under the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights.’

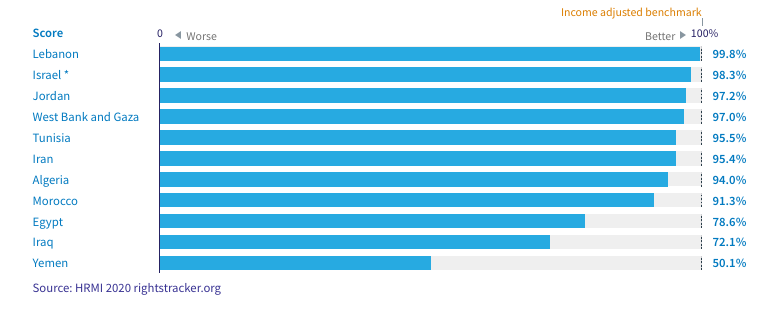

Dr Randolph points out that, ‘Jordan turns in its best performance on the right to work, scoring 97.2% of what should be possible given its resources. This suggests that many people in Jordan are enjoying their right to work. However, the low right to education score of 61.9% suggests that many Jordanians are not able to access education. Refugees and immigrants, in particular, are at risk of violations to their right to education.’

Human rights in Jordan: Themes from the data

Human rights are crucial for surviving the pandemic

HRMI’s economic and social rights lead, Dr Susan Randolph, says this:

‘A focus on human rights is even more important in the context of Covid-19. Marshalling resources to improve human rights can simultaneously help stem the pandemic. How can people protect themselves by washing their hands if they don’t have access to running water? How can people maintain social distance if they are homeless or living in an overcrowded home? How can people know to quarantine themselves when they feel ill if they don’t have access to tests? How can we prevent the deaths of those that contract Covid-19 if people don’t have access to affordable healthcare? It’s not just a matter of stemming the pandemic, but also of focusing our admittedly more limited resources on those factors that make the most difference to people’s lives.’

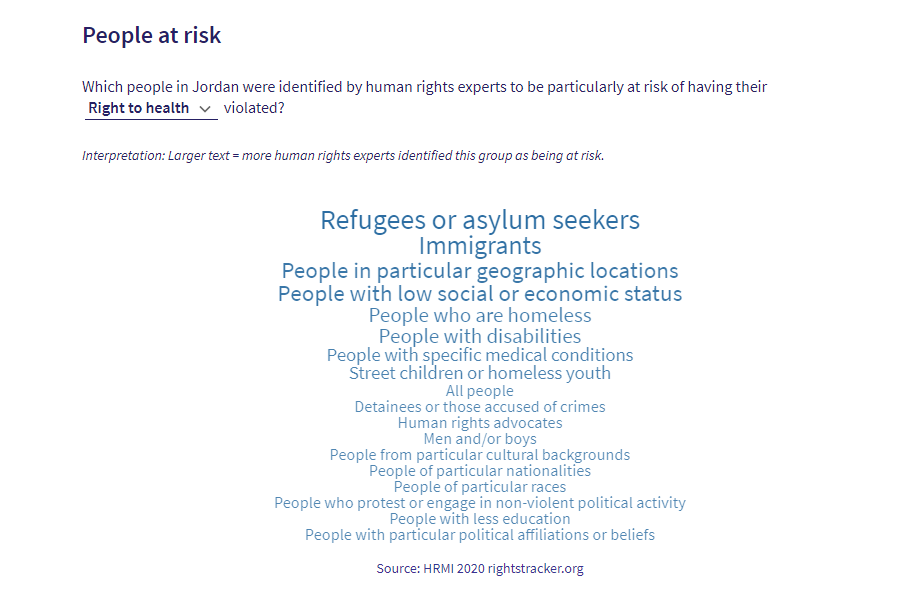

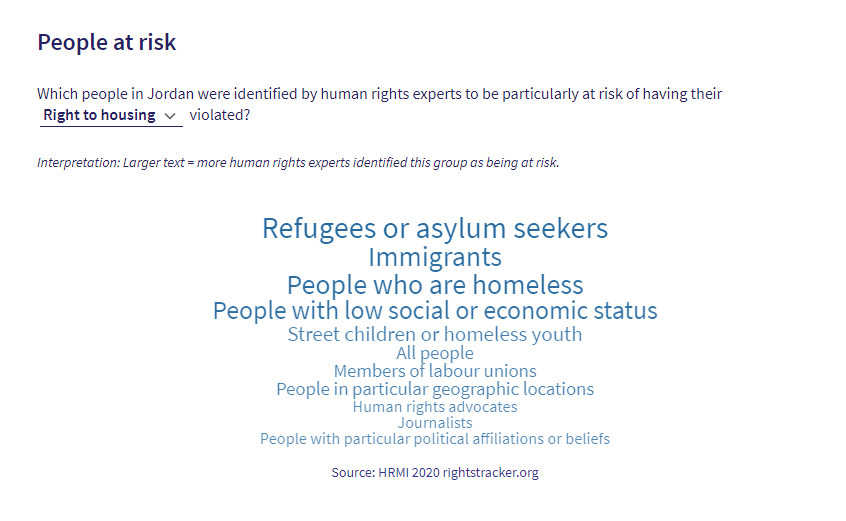

Refugees, asylum seekers, and immigrants suffer high levels of human rights violations

Jordan’s history of welcoming refugees, asylum seekers, and immigrants has been tested since the Syrian civil war began in 2011. Experts identified refugees, asylum seekers, and immigrants as particularly vulnerable to abuses related to quality of life. This is particularly significant given Jordan’s generally high quality of life scores.

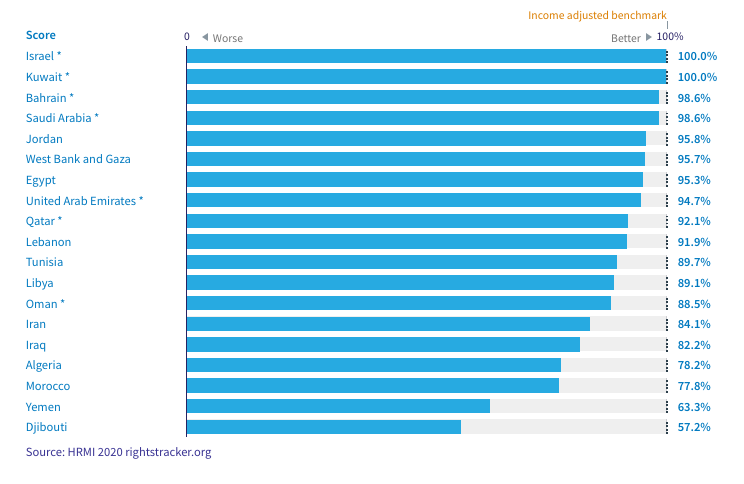

Encouraging scores for quality of life rights

Overall, Jordan’s Quality of Life score is in the ‘fair’ range, but its scores for the rights to housing and work are nearly as good as any country with its level of resources, and among the higher scores in the Middle East and North Africa region, as you can see in the charts below:

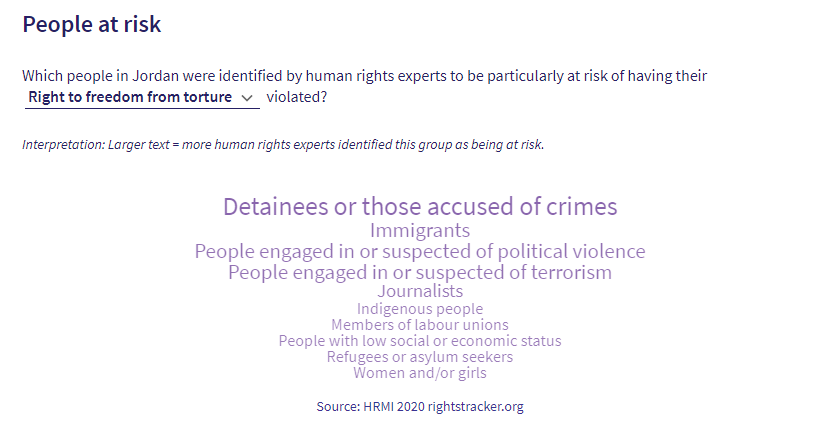

Detainees or those accused of crimes lack safety from the state

Our human rights experts identified detainees or those accused of crimes as being at particular risk of violations of the rights we measure for safety from the state, particularly:

- the right to freedom from arbitrary arrest

- the right to freedom from disappearance

- the right to freedom from the death penalty

- the right to freedom from torture.

Journalists’ freedom of association at risk

Our respondents repeatedly identified journalists as particularly vulnerable to abuses regarding their rights to assembly and association, right to opinion and expression, and right to participate in government.

Worryingly low levels of political empowerment in Jordan

Jordan’s Empowerment score of 4 out of 10 is worse than average when compared to the other 28 countries we have these data for. Further, there has been no improvement over the last three years.

Journalists, members of labour unions, and people engaged in or suspected of political violence were identified as being particularly affected.

Experts highlight threats to the rights of children and young people

Children were identified as being particularly vulnerable to abuses of these rights:

- the right to participate in government

- the right to assembly and association

- the right to opinion and expression.

For the first time this year HRMI included ‘street children and homeless youth’ as a group respondents could choose. Experts said that street children and homeless youth in Jordan were at risk of many human rights violations, including of:

- the right to food

- the right to housing

- the right to health

- the right to education

- right to work.

About the Human Rights Measurement Initiative (HRMI, pronounced ‘her-mee’)

HRMI is a global, not-for-profit data analysis organisation that aims to improve people’s lives by producing user-friendly, reliable information on the human rights progress of countries.

‘HRMI is filling a gap in human rights data, providing human rights practitioners with powerful tools to show governments how they are

performing, and remind them of the promises they’ve made by signing human rights treaties.’— Anne-Marie Brook

Co-founder and Development Lead Anne-Marie Brook, a former economist, based in Wellington, New Zealand, says, ‘We know that it is hard for countries to make progress if good data aren’t available that show how they’re actually doing. HRMI is filling a gap in human rights data, providing human rights practitioners with powerful tools to show governments how they are performing, and remind them of the promises they’ve made by signing human rights treaties.’

How HRMI produces the scores

HRMI human rights scores are produced by two teams of researchers.

Co-founder and Economic and Social Rights Lead Dr Susan Randolph produces scores for up to five Quality of Life rights, for around 200 countries, using indicator data supplied by countries to international databases. Dr Randolph then analyses the data using the award-winning SERF Index she developed with her colleagues, Sakiko Fukuda-Parr and Terra Lawson-Remer.

‘The SERF Index is unique because it takes into account a country’s financial resources,’ Dr Randolph explains. ‘The income-adjusted score shows how close a country is to meeting its urgent duty, compared with other countries with similar resources – for these rights, the realistic target is 100%.’

‘The HRMI Country Report tells people whether their government is doing its best with the country’s resources to give full effect to their economic and social rights, or whether there is room for improvement.’

Co-Founder and Civil and Political Rights Lead, Dr K Chad Clay from the University of Georgia, in the United States, heads up the data collection and analysis for HRMI’s Empowerment and Safety from the State measurements.

These rights are politically sensitive to measure, and HRMI is the first global project to track them systematically, country by country. In 2020 HRMI produced data for 33 countries, and is ready to expand to the rest of the world once sufficient funding is secured.

‘We know that the best sources of information on human rights in a country are the people directly monitoring conditions in that country. So we designed a detailed expert survey to be filled out by human rights practitioners, like lawyers, journalists, and advocates, including people working for organisations like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch. We collected data in February and March of 2020, asking about the situation in their country in 2019 and 2018. We then used statistical techniques to be sure we were providing the most accurate and honest information possible. Now we’re presenting our findings in scores out of ten for each of the seven civil and political rights we measure.’

‘We want to create a global competition, where countries compete to treat people better.’

— Anne-Marie Brook

HRMI works on an annual cycle and is already preparing to collect data about 2020, ready for publication in 2021. As funding increases, HRMI is ready to:

- expand to cover more countries

- measure performance on more rights, and

- provide more detail on performance, such as separating out scores by sex and race.

‘We want to create a global competition, where countries compete to treat people better,’ Ms Brook says. ‘As we repeat our data collection annually, we hope to see countries improve, until people everywhere are thriving and safe.’

Our full dataset is available for free download from our Rights Tracker, and all data and graphics on our Rights Tracker are freely available for you to use under a Creative Commons licence.

Thanks for your interest in HRMI. To further explore our human rights data for New Zealand, please visit our Rights Tracker, where you can find data by country or right.