Nigerians are fighting for better rights outcomes

The Human Rights Measurement Initiative (HRMI) is the first global initiative to track the human rights performances of countries. This country profile focuses on the economic and social rights outcomes for Nigeria. All data discussed below are available on our Rights Tracker. See also HRMI’s Research credentials. This country spotlight refers to data published in 2020.

Nigeria is fortunate to have a strong civil society that actively lobbies for openness and accountability in government.

Enthusiasm and hard work are slowly helping shape legislation across many sectors; for example, the National Minimum Wage (Amendment) Act 2011 raised the national minimum wage and introduced a penalty for those who do not pay employees the minimum wage; the National Health Act was established in 2014 to develop and manage a national health system and to set standards for health services; and the Trafficking in Persons (Prohibition), Enforcement and Administration Act was adopted in 2015 to reflect Nigeria’s commitment to protect victims of human trafficking and to promote national and international cooperation in this space.

Many challenges remain. Nigeria faces extreme poverty, insecurity, rising unemployment, and bad governance (OHCHR, 2019 — link no longer available). In addition, Nigerian police regularly commit human rights violations such as torture, unlawful violence, intimidation, and harassment, particularly against human rights defenders and journalists (Amnesty International, 2013).

It is promising that Nigerians are fighting for better rights and rights outcomes, as there is clearly still a gap between what people want and what the government is doing.

It is promising that Nigerians are fighting for better rights and rights outcomes, as there is clearly still a gap between what people want and what the government is doing.

In this article you can read every section to understand HRMI’s data in detail, or skip to the Nigeria-specific sections, for some examples of how Nigeria’s change-makers can use our data to work for human rights improvements.

Headlines

Keep reading for more information on these headlines that come from HRMI’s human rights data:

- If Nigeria were to operate at its full potential given its current resources, we would expect an additional 12 million children under five to grow well and not be stunted.

- If Nigeria were operating at best practice, we would expect an extra 3.6 million additional children to reach their fifth birthday.

- If Nigeria used its resources efficiently, an additional 122 million people could have access to basic sanitation and an extra 143 million people could have access to water on site.

- If Nigeria were operating at its full potential given its current resources, it could lift 118 million people out of absolute poverty.

- If Nigeria were using its resources effectively, an extra 9.3 million primary school aged children could be enrolled in primary school.

How do HRMI’s data work?

HRMI data can help boost efforts to improve people’s lives in Nigeria by giving definitive scores measuring government performance on economic and social rights outcomes. Each rights score can then be used to show where change is needed most and how these changes can be achieved.

So, how does HRMI work? HRMI’s ground-breaking methodology allows us to score countries on how well they use their income for economic and social rights (ESR) outcomes. In particular, our current data focus on the rights to food, health, housing, work, and education. To calculate a country’s ESR scores we use the SERF Index methodology, developed by HRMI co-founder Susan Randolph and her colleagues Sakiko Fukuda-Parr and Terra Lawson-Remer.

The SERF Index combines country achievement and country income to produce a ‘best practice’ benchmark that records the best results that any country has achieved over the last 20 years, at every income level. Each country’s current achievement level is then compared to the best practice outcome for its income level and given an ESR score as a percentage of that result. So any score that’s less than 100% is showing that there’s a gap between how that country is doing, and the best result of any other country with the same level of income.

The ESR scoring methodology takes income into account so it can assess all countries on a level playing field. It can then be used to reveal how a country can improve its rights performance, and by how much, even without more income or resources.

Our scoring methodology takes income into account so it can assess all countries on a level playing field.

When a country scores 100% on the performance of a right, it means that the government is keeping its human rights promises to do its very best for its people within the constraints of the country’s resources. All countries can score 100%. Any score below 100% shows that there is realistic room for improvement, even at the country’s current level of resources. An underperforming country can use HRMI’s ESR scores to see which of their nearby countries are doing better and identify policy lessons from them.

There is a lot of cross-over between HRMI’s human rights performance indicators and the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) targets and benchmarks. Countries can use HRMI’s scores to evaluate their own progress and their potential to reach the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, given their current level of income.

HRMI’s benchmarks and assessment standards

HRMI’s methodology uses two benchmarks and two assessment standards when evaluating a country’s ESR performance.

The first benchmark is ‘income adjusted’. Using this benchmark, countries are compared with other countries of a similar income level, allowing us to evaluate how effectively each country is using its available resources.

The second benchmark is ‘global best’. This benchmark evaluates country performance relative to the best performing countries at any level of resources.

Both benchmarks use two assessment standards when evaluating country performance, which use slightly different sets of indicators for low and middle income countries and for high income countries. Each assessment standard uses a set of indicators that are commonly available and most relevant for these countries. Every country gets assessed on both standards to the extent the information is available in international databases.

HRMI’s data are useful for Nigeria’s change-makers

Let’s explore the economic and social rights performance of Nigeria using HRMI’s ESR data. The population of Nigeria in 2018 was 195.9 million, at which time Nigeria had a GDP per capita of $5,316 (in 2011 PPP dollars). Therefore, HRMI ESR metrics for Nigeria are best assessed against the income adjusted performance benchmark using the low-and-middle-income assessment standard.

Right to Food

Nigeria’s right to food score is 40.2%, which is based on the percentage of children under five that are not stunted.

We use child stunting as a high-level ‘bellwether’ indicator to reveal how many Nigerians are not getting enough energy and nutrients from their diets to grow normally. (For more on this, please see our Methodology Handbook.)

This score means Nigeria is only doing 40.2% of what should be possible with its current GDP per capita to ensure the enjoyment of the right to food.

Comparing this score between sexes suggests that females experience the right to food slightly more so than males. Specifically, Nigerian females have a right to food score of 60.2% while Nigerian males have a score of 53.7%.

On the Rights Tracker, you can also see trends over time in our scores. Here’s the time graph for the right to food:

Note that data for Nigeria’s right to food indicator is most recently available in 2016. This means it is not yet possible to determine whether Nigeria has made any improvements toward ensuring the right to food since its score decreased between 2015 and 2016.

If Nigeria were operating at best practice, as some of its neighbours are doing, it could lift the percentage of children under five that are not stunted from 56.4% to 94.2% — nearly solving the problem of hunger in the country. The right to food relates directly to SDG 2: Zero Hunger, which aims to end all forms of starvation by 2030.

If Nigeria were to operate at its full potential given its current resources, 12 million additional children under five would have a better chance of not being stunted, and make significant gains toward SDG 2’s target of ending starvation by 2030.

Right to Health

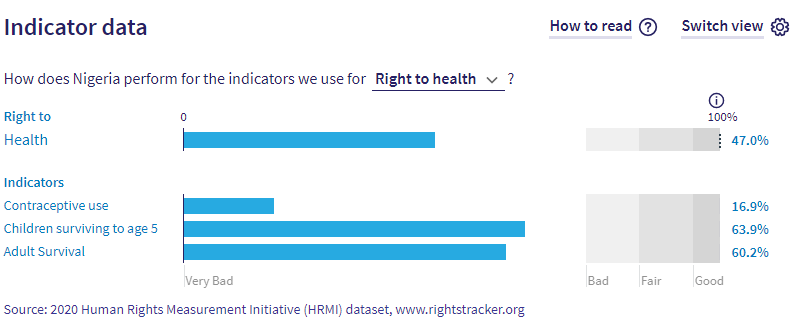

Nigeria’s right to health score is 47.0%.

As shown in the image below (taken from the Nigeria page of our publicly available Rights Tracker), this score comes from three indicators: the use of contraception by women ages 15 to 49 years who are married or in-union (16.9%); children surviving to age five (63.9%); and adult survival (60.2%).

On average, these scores suggest the extent to which people enjoy the right to health is approximately 47% as high as it could be, even at Nigeria’s current income level.

Significantly, when we line up all sub-Saharan African countries in order of their HRMI scores, Nigeria is ranked 44th out of 45 countries. This tells us that Nigeria’s policy-makers could look to many of its neighbours with similar incomes, who are doing much better, for examples of ways to make improvements.

These right to health indicators collectively relate to SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being, as well as SDG 1: No Poverty.

If Nigeria were operating at best practice, an extra 3.6 million additional children would have a much better chance of reaching their fifth birthday, contributing to SDG 3’s target of ending preventable deaths of children under five by 2030.

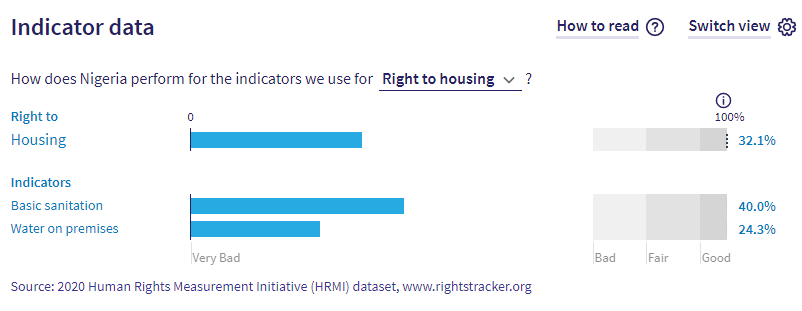

Right to Housing

Nigeria’s ESR score for the right to housing is 32.1%. As illustrated by the Rights Tracker screenshot below, this score is averaged across two indicators: access to basic sanitation (40.0%), and access to drinking from an improved water source on site (24.3%). These indicators relate to SDG 1: No Poverty, SDG 6: Clean Water and Sanitation, and SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities.

If Nigeria used its resources efficiently, an additional 122 million people could have access to basic sanitation and an extra 143 million people could have access to water on site.

Right to Work

Nigeria’s right to work score is 22.7%, as measured by the percentage of people not in absolute poverty, where the absolute poverty line is set at $3.20 (2011 PPP$) per day.

This means Nigeria is only achieving 22.7% of what should be possible with its current income to ensure the right to work is enjoyed by all. When comparing right to work scores across sub-Saharan African countries, Nigeria sits near the bottom, with only Malawi and Madagascar having lower scores.

The good news, however, is that there are plenty of countries that Nigeria can to look to for inspiration, such as Mauritius and Gabon, who are also low-income Sub-Saharan countries but instead have much higher right to work scores than Nigeria.

It is important to note that Nigeria’s right to work score is based on 2009 data. Therefore, it is possible that Nigeria has made improvements on this front, but reliable data are yet to be released for the right to work indicator.

This indicator relates to SDG 1: No Poverty and SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth.

If Nigeria were operating at its full potential given its current resources, it could lift 118 million people out of absolute poverty and make significant steps toward SDG 1 of eliminating extreme poverty by 2030.

Right to Education

HRMI uses two indicators under the low and middle income assessment standard for the right to education, both of which reflect SDG 4: Quality Education and SDG 1: No Poverty. The first indicator is the total number of students of the official primary school age group who are enrolled in primary or secondary education. Nigeria scores 43.5% on this indicator.

The second indicator relates to secondary school enrolment, however international databases do not have enough information to measure this indicator in Nigeria. For this reason, we are unable to produce Nigeria’s overall right to education score, or its Quality of Life score (reflecting performance across all five economic and social rights).

If Nigeria were using its resources effectively, an extra 9.3 million primary school-aged children could be enrolled in primary school.

Nigeria’s overall rights performance

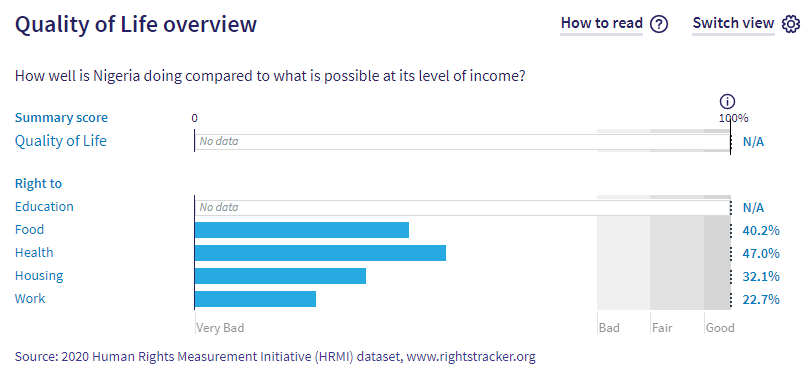

HRMI’s economic and social rights scores for Nigeria are summarised in the Rights Tracker image below. Since Nigeria’s right to education data are incomplete, we are unable to compute an overall Quality of Life score.

You can compare Nigeria’s four rights scores with other countries’ scores by clicking on each of the rights: right to food, right to health, right to housing, and right to work.

Note: It is worth being mindful of the year that the data were collected for each of Nigeria’s rights indicators. Data on the indicators for the rights to health and housing were most recently observed in 2017, and the right to food in 2016. However, data for Nigeria’s right to work and right to education indicators were most recently recorded in 2009 and 2010, respectively. Therefore, it is possible that Nigeria has made progress in the performance of these latter rights, but such (potential) progress is not yet reflected in any credible data source.

Next steps: what can you do now?

If you are advocating for human rights in Nigeria or working towards the SDGs, HRMI data can point out new opportunities for progress. Here are some ways you can use our data to lead to change:

1. Look for the countries that are similar to Nigeria in income, but scoring much better. You can filter the rights pages on our Rights Tracker by region and income level, so just click on these rights to get started, and choose a filter at the top left: right to food, right to health, right to housing, and right to work.

You can find which countries have similar levels of income using this list, arranged by GDP per capita.

2. Ask what those similar and high-performing countries are doing differently.

3. Copy key facts from the Rights Tracker and this article to use in your reports and advocacy. Isn’t it compelling to tell the government, or the public, that with better management, over 3 million more children could live past their fifth birthday?

All our data are freely available for you to use. We would love to hear if you use our work!

4. Watch out for the next annual update of the scores in May or June each year — is Nigeria improving, either in its score or its place on the table?

5. Get in touch with us if you need any help at all. We would be delighted to partner with you in your work to improve people’s lives.

Thanks for your interest in HRMI. To further explore our human rights data for Nigeria, please visit our Rights Tracker, where you can find data by country or right.