Quality of life in Canada: some room for improvement

The Human Rights Measurement Initiative (HRMI, pronounced ‘her-mee’) is the first global project to track the human rights performance of countries. Its 2021 Human Rights Rights Tracker gives human rights scores on up to 13 different human rights contained in United Nations treaties, for around 200 countries.

The 2021 Rights Tracker scores for Canada include many positive scores, but also some strikingly poor results, particularly in terms of poverty.

Headlines (further details below):

- Marked inequities in Canadians’ quality of life

- Canada is performing poorly on ensuring safely managed sanitation

- Too many Canadians living in relative poverty

- Canadian children and young people missing out on a quality education

The economic and social rights scores for Canada were calculated in 2021, using the most recently available figures from international databases. This means the Rights Tracker now has scores for every year from 2008-2018.

Canada is not yet included in our annual human rights survey, so we do not yet produce civil and political rights data for Canada. (If you can help fund Canada’s inclusion in the survey, please contact us.)

This also means that for Canada, we provide only limited information on which groups of people are most affected by rights violations. For comparison, see the extra ‘people at risk’ data available for Brazil. We look forward to including this kind of information in future datasets.

Summary: Quality of Life in Canada

The Quality of Life scores are produced by using data from international databases, and measuring outcomes against the best we could expect at each country’s income level.

HRMI co-founder and Economic and Social Rights Lead Dr Susan Randolph explains that, ‘Canada’s scores imply that with the resources it has, Canada can do much more than it currently is, to ensure its people enjoy their economic and social rights. As such, it has a long way to go to meet its obligations under the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights.’

Dr Randolph points out that, ‘Canada turns in its best performance on the right to food, scoring 94.7% of what should be possible given its resources.’

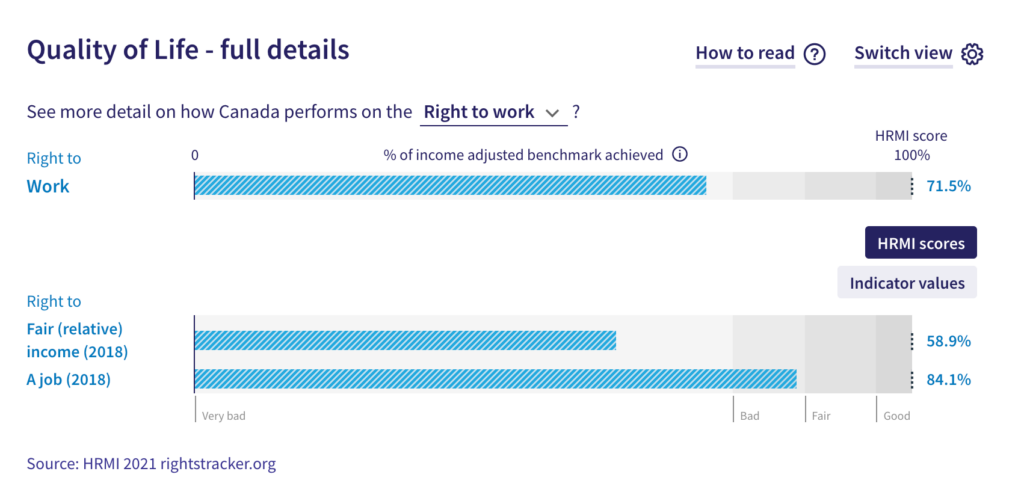

Canada’s worst score of 71.5% for the right to work falls into the ‘very bad’ range, driven by a very low score for preventing relative poverty.

Human rights in Canada: Themes from the data

Marked inequities in Canadians’ quality of life

For all four Quality of Life rights we measured, Canada has some way to go to meet its human rights obligations. Canada’s scores fall into the ‘fair’ and ‘very bad’ ranges.

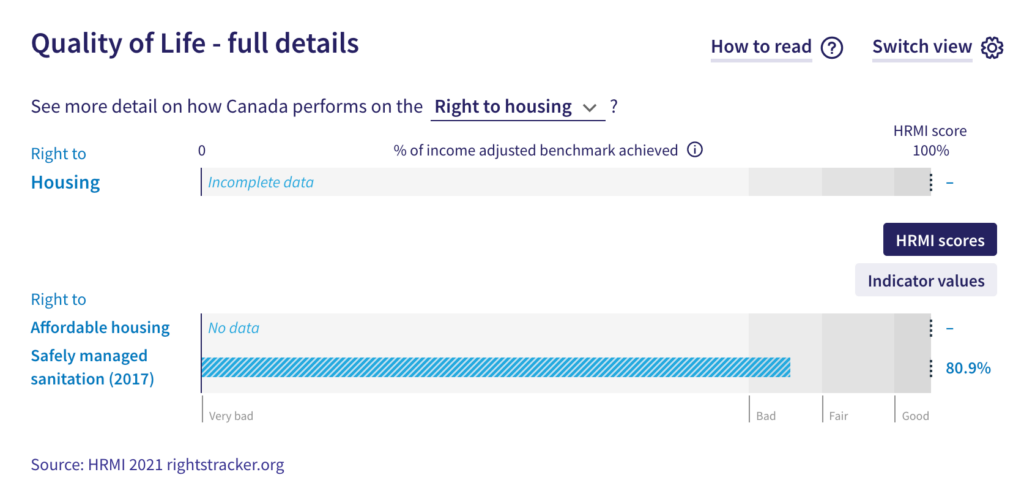

Canada is performing poorly on ensuring safely managed sanitation

The right to housing comprises two rights, to affordable housing and to safely managed sanitation. Internationally comparable data for affordable housing is unavailable for Canada, but our score on safely managed sanitation shows that Canada is performing quite poorly in this regard.

The score is 80.9%, which is in the ‘bad range’ which means that Canada has the resources to ensure many more people in Canada have access to safely managed community sanitation facilities.

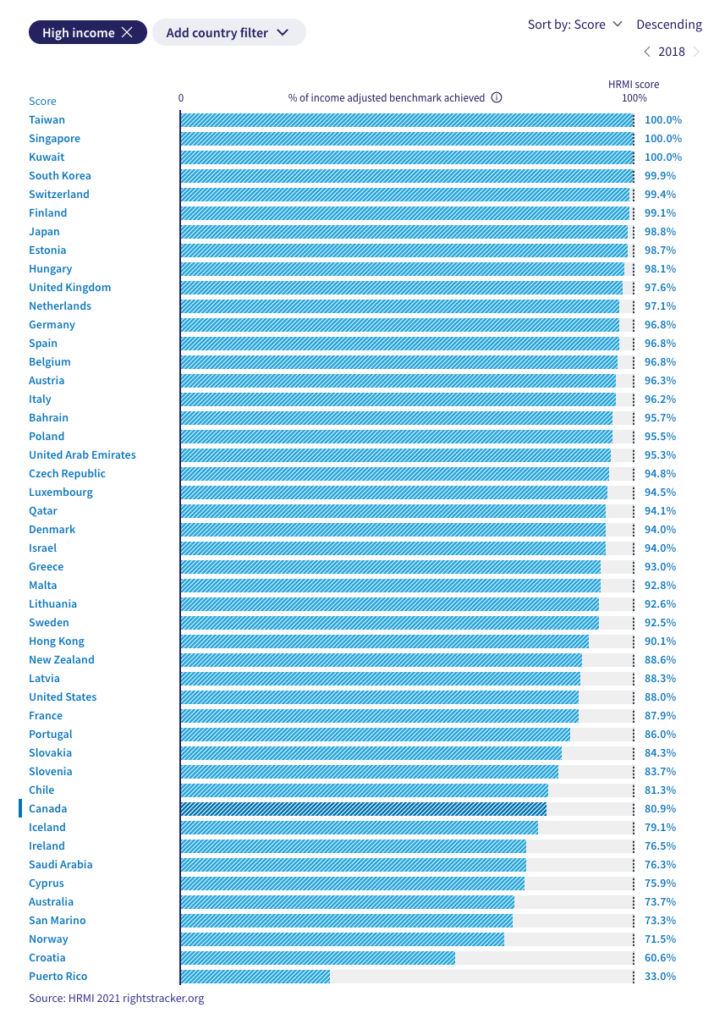

Compared to the other high income countries we measure for safely managed sanitation, Canada is ranked 38th out of 47.

Many other high income countries are doing much more for their people in regard to sanitation facilities. Canada has a long way to go to match up to the countries that are making the best use of their resources, such as Taiwan, Singapore and Kuwait.

Too many Canadians live in relative poverty

The right to work combines the right to a job and the right to a fair income.

Canada scores only 58.9% for the right to fair income. The score falls within the ‘very bad’ range and also brings down the overall score for right to work, which is 71.5%, despite a better score of 84.1% for the right to a job. This situation needs to be improved in Canada.

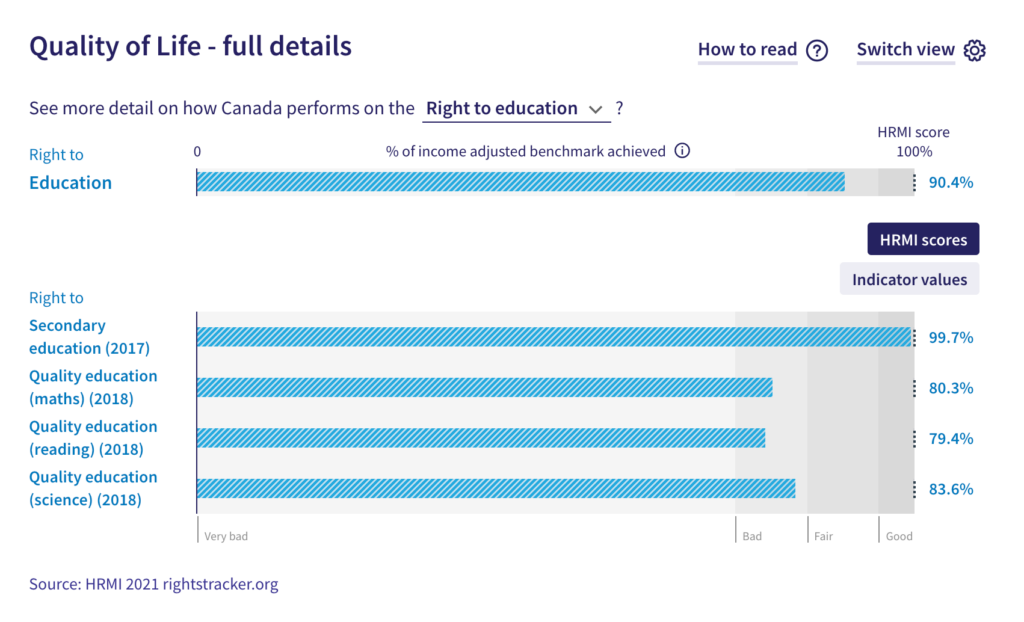

Canadian children and young people missing out on quality education

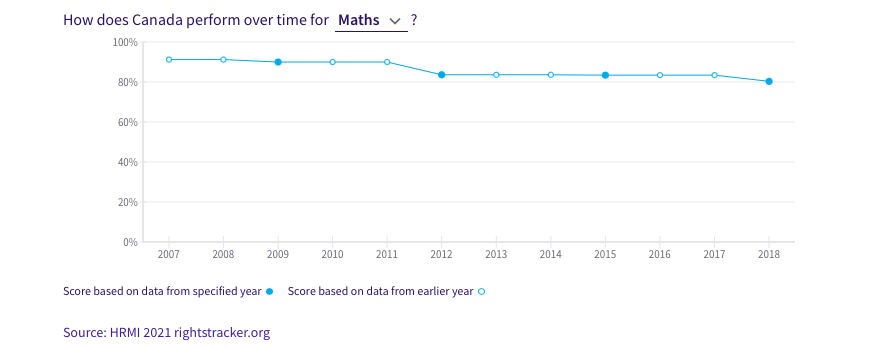

HRMI measures four aspects of the right to education: secondary education, quality education (maths), quality education (reading) and quality education (science). Canada performs very well when it comes to access to and enrolment in secondary education, where the score for government performance is 99.7% (reflecting an underlying enrolment rate of 99.8%).

However, for the measurements of quality education, all three scores fall in the ‘bad’ range, which is alarming.

Steady fall in education scores a cause for concern

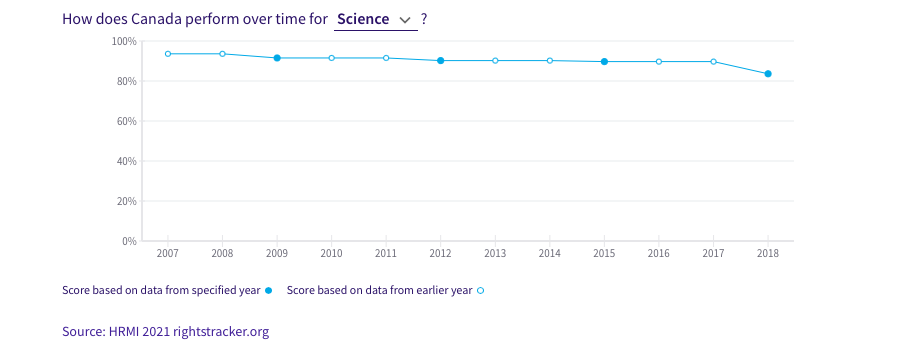

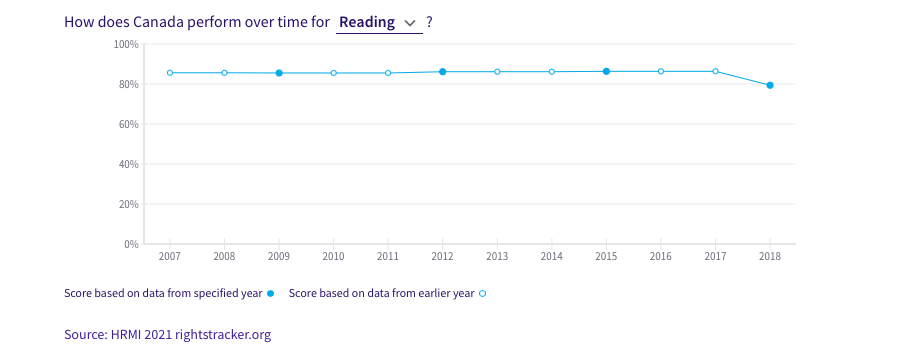

Canada’s quality education scores have been dropping slightly over the years 2007-2018.

Those responsible for the quality of education in Canada may wish to examine the HRMI data for the right to education, and consider what steps can be taken to improve performance.

About the Human Rights Measurement Initiative (HRMI, pronounced ‘her-mee’)

HRMI is a global, not-for-profit human rights data platform that aims to improve people’s lives by producing user-friendly, reliable information on the human rights progress of countries.

‘HRMI is filling a gap in human rights data, providing human rights practitioners with powerful tools to show governments how they are

performing, and remind them of the promises they’ve made by signing human rights treaties.’— Anne-Marie Brook

Co-founder and Development Lead Anne-Marie Brook, an economist and social entrepreneur, based in Wellington, New Zealand, says, ‘We know that it is hard for countries to make progress if good data aren’t available that show how they’re actually doing. HRMI is filling a gap in human rights data, providing human rights practitioners with powerful tools to show governments how they are performing, and remind them of the promises they’ve made by signing human rights treaties.’

How HRMI produces the scores

HRMI human rights scores are produced by two teams of researchers.

Co-founder and Economic and Social Rights Lead Dr Susan Randolph produces scores for up to five Quality of Life rights, for around 200 countries, using indicator data supplied by countries to international databases. Dr Randolph then analyses the data using the award-winning SERF Index she developed with her colleagues, Sakiko Fukuda-Parr and Terra Lawson-Remer.

‘The SERF Index is unique because it takes into account a country’s financial resources,’ Dr Randolph explains. ‘The income-adjusted score shows how close a country is to meeting its urgent duty, compared with other countries with similar resources – for these rights, the realistic target is 100%.’

‘The HRMI Country Report tells people whether their government is doing its best with the country’s resources to give full effect to their economic and social rights, or whether there is room for improvement.’

You can watch this short animated video for a further explanation of how we create the scores:

Co-Founder and Civil and Political Rights Lead, Dr K Chad Clay from the University of Georgia, in the United States, heads up the data collection and analysis for HRMI’s Empowerment and Safety from the State measurements, which we are not yet able to produce for Canada.

These rights are politically sensitive to measure, and HRMI is the first global project to track them systematically, country by country. In 2021 HRMI produced data for 39 countries, and is ready to expand to Canada and rest of the world once sufficient funding is secured.

‘We know that the best sources of information on human rights in a country are the people directly monitoring conditions in that country. So we designed a detailed expert survey to be filled out by human rights practitioners, like lawyers, journalists, and advocates, including people working for organisations like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch. We collected data in February and March of 2021, asking about the situation in their country in 2020 and 2019. We then used statistical techniques to be sure we were providing the most accurate and honest information possible. Now we’re presenting our findings in scores out of ten for each of the eight civil and political rights we measure.’

‘Our vision is a world where countries are competing to see who can treat people the best.’

— Anne-Marie Brook

HRMI works on an annual cycle and is already preparing to collect data about 2021, ready for publication in 2022. As funding increases, HRMI is ready to:

- expand to cover more countries

- measure performance on more rights, and

- provide more detail on performance, such as separating out scores by sex and race.

‘We want to create a global competition, where countries compete to treat people better,’ Ms Brook says. ‘As we repeat our data collection annually, we hope to see countries improve, until people everywhere are thriving and safe.’

Thanks for your interest in HRMI. To further explore our human rights data for Canada, please visit our multilingual Rights Tracker, where you can find data by country or right.