Vietnam’s Journalists and union members suffer human rights violations

The 2020 Country Report on Vietnam provides a mixed picture of how the government treats people.

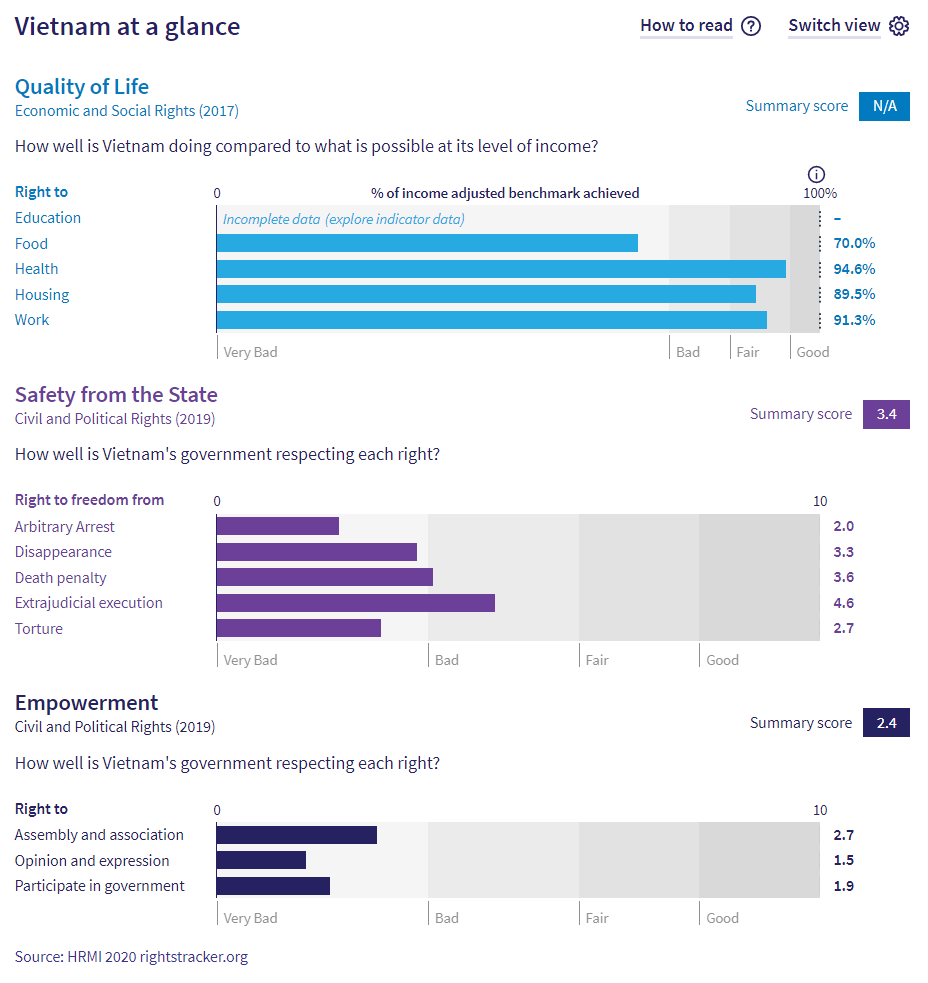

Of the 13 rights HRMI measures, none of Vietnam’s scores are high enough to reach the ‘good’ band, and only three scores reach the next ‘fair’ band — scores for the rights to health, work, and housing.

Our data show that Vietnam has a long way to go before its people can have full enjoyment of their civil and political rights.

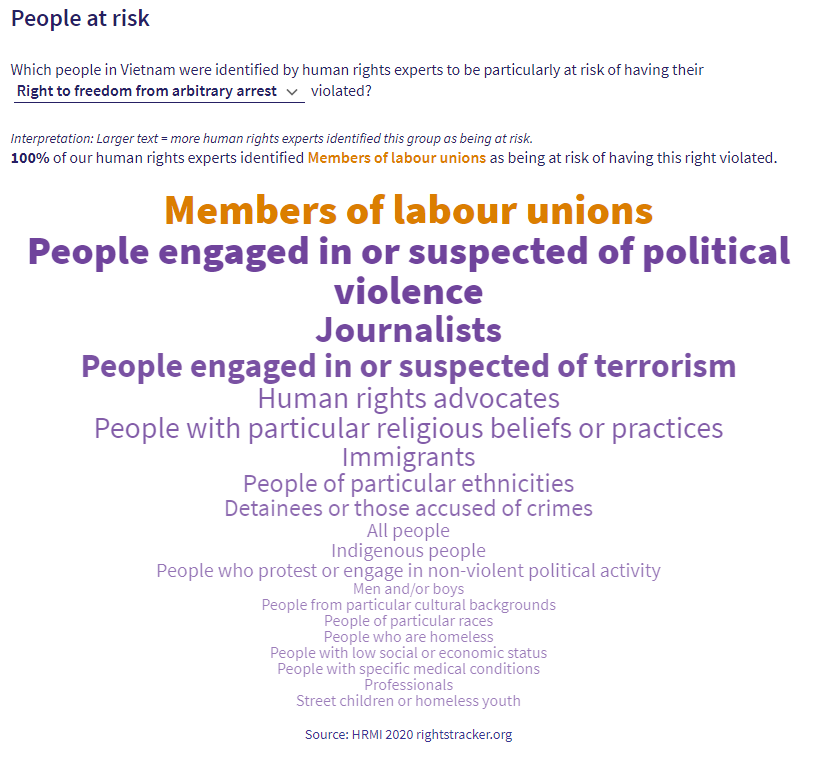

Several groups of people were consistently identified by high numbers of our experts as being at risk of having these rights violated, including:

- Members of labour unions

- Journalists

- People engaged in or suspected of political violence or terrorism

- People with particular religious beliefs or practices.

Below is an overview of HRMI’s human rights report for Vietnam, as seen on our Rights Tracker

How HRMI produces the scores

HRMI human rights scores are produced by two teams of researchers.

Co-founder and Economic and Social Rights Lead Dr Susan Randolph produces scores for up to five Quality of Life rights, for around 200 countries, using indicator data supplied by countries to international databases. Dr Randolph then analyses the data using the award-winning SERF Index she developed with her colleagues, Sakiko Fukuda-Parr and Terra Lawson-Remer.

‘The SERF Index is unique because it takes into account a country’s financial resources,’ Dr Randolph explains. ‘The income-adjusted score shows how close a country is to meeting its urgent duty, compared with other countries with similar resources.’

‘The HRMI Country Report tells people whether their government is doing its best with the country’s resources to give full effect to their economic and social rights, or whether there is room for improvement.’

Co-Founder and Civil and Political Rights Lead, Dr K Chad Clay from the University of Georgia, in the United States, heads up the data collection and analysis for HRMI’s Empowerment and Safety from the State measurements.

These rights are politically sensitive to measure, and HRMI is the first global project to track them systematically, country by country. In 2020 HRMI produced data for 33 countries, and is ready to expand to the rest of the world once sufficient funding is secured.

‘We know that the best sources of information on human rights in a country are the people directly monitoring conditions in that country. So we designed a detailed expert survey to be filled out by human rights practitioners, like lawyers, journalists, and advocates, including people working for organisations like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch. We collected data in February and March of 2020, asking about the situation in their country in 2019 and 2018. We then used statistical techniques to be sure we were providing the most accurate and honest information possible. Now we’re presenting our findings in scores out of ten for each of the eight civil and political rights we measure.’

There is a lot of cross-over between HRMI’s human rights performance indicators and the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) targets and benchmarks. Countries can use HRMI’s scores to evaluate their own progress and their potential to reach the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, given their current level of income.

HRMI’s benchmarks and assessment standards

HRMI’s methodology uses two benchmarks and two assessment standards when evaluating a country’s ESR performance.

The first benchmark is the ‘income adjusted’ benchmark. Using this benchmark, countries are compared with other countries of a similar income level, allowing us to evaluate how effectively each country is using its available resources. The second benchmark is the ‘global best’ benchmark. This benchmark evaluates country performance relative to the best performing countries at any level of resources.

Both benchmarks are useful for different purposes. The country scores measured against the income adjusted benchmark show how effectively a country is using its resources to achieve good rights outcomes. This also tells us how much its performance can be improved even without extra income. The scores measured against the global best benchmark show how far a country has to go to do as well as any country in the world. These global best scores are important because even if a government is doing its best with their current resources (so it has an income adjusted rights score close to 100%), a country with very low income will likely still have many people not fully enjoying their human rights, which will be reflected in low scores when measured against the global best benchmark.

The assessment standard tells us which collection of rights indicators we use to evaluate the ESR performance of a country. The difference between the two assessment standards is to do with the availability and relevance of data for low and middle income countries versus high income countries.

The low and middle income assessment standard includes rights indicators which low and middle income countries are more likely to have data on, and/or which are more relevant to the rights challenges they currently face. The high income assessment standard includes rights indicators high income countries are most likely to have data on, and/or which are more relevant to the rights challenges they face.

For example, when figuring out how well countries are doing at fulfilling the right to education, for low and middle income countries we look at primary and secondary school enrolment rates. This tells us about access to education. Both indicators are widely available for low and middle income countries and vary widely across them.

But in high income countries, primary school enrolment is essentially universal, so this indicator isn’t a very useful measure of access to education. Instead, for our high income assessment standard we use the secondary school enrolment rate as our single indicator of access, but we also include an indicator of school quality: student performance on the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) tests. School quality is no less a concern for low and middle income countries, but unfortunately, at this time there is no test of student performance that is widely used by low and middle income countries.

We do produce scores on all indicators for all countries if the data are available. So, for example, you can see HRMI scores related to a low income country’s PISA results if that country participates in the PISA assessments.

It can be useful to toggle between the two assessment standards, and check out our scores on the individual indicators, on the country pages of the Rights Tracker.

HRMI’s data are useful for Vietnam’s change-makers

Let’s explore the economic and social rights performance of Vietnam using HRMI’s ESR data. The population of Vietnam in 2018 was 95.5 million, at which time Vietnam had a GDP per capita of $6,609 (in 2011 PPP dollars). Therefore, HRMI ESR metrics for Vietnam are best assessed against the income adjusted performance benchmark using the low and middle income assessment standard.

Indigenous people, homeless people, and those of lower socioeconomic status are most likely to suffer from a low quality of life

Vietnam is performing better than average compared to other countries in East Asia when it comes to economic and social rights. However, those of certain races or ethnicities, particularly the Montagnard and H’mong peoples, are at risk of not enjoying their rights to education, food, health, and work.

Street children or homeless youth, as well as homeless people, are listed in the at-risk groups for every right.

Vietnam improving in rights to housing and work, but right to food still lags

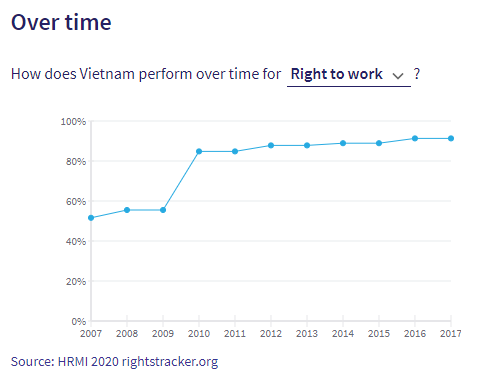

Vietnam is performing better than many countries in East Asia for the rights to housing (89.5%), work (91.3%), and health (94.6%). This suggests that the Vietnamese government is using its resources fairly effectively so that people have access to housing and work. These scores have also increased steadily since 2007, suggesting that the quality of life in Vietnam is increasing.

However, Vietnam performs more poorly on the right to food, with a score of only 70%. This score suggests that Vietnam could be using its resources more effectively to allow more people to enjoy their right to food.

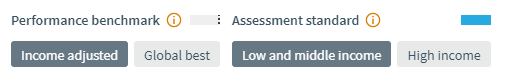

Right to Food

The right to food relates directly to SDG 2: Zero Hunger, which aims to end all forms of starvation by 2030. Vietnam’s right to food score is 70.0%, which is based on the percentage of children under five that are not stunted.

We use child stunting as a high-level ‘bellwether’ indicator to reveal how many Vietnamese are not getting enough energy and nutrients from their diets to grow normally. (For more on this, please see our Methodology Handbook.)

Comparing this score with other low and middle incomes countries in East Asia and the Pacific, Vietnam is ranked in the middle of the list, along with Vanuatu and Nauru. Vietnam could look to South Korea, Australia, Tuvalu, and Samoa for policy advice on how to improve right to food outcomes.

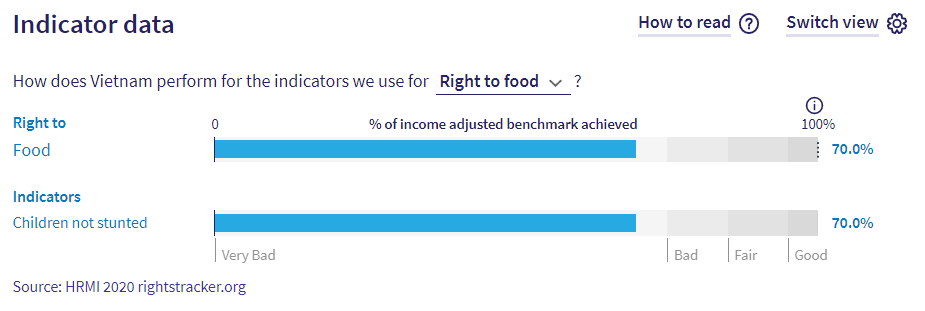

Right to Health

Vietnam’s right to health score is 94.6%.

As shown in the image below, this score comes from three indicators: the use of contraception by women ages 15 to 49 years who are married or in-union (score = 95%); children surviving to age five (score = 96.1%); and adult survival (score = 92.7%).

On average, these income adjusted indicator scores suggest the extent to which people enjoy the right to health is approximately 94.6% as high as it should be at Vietnam’s current income level.

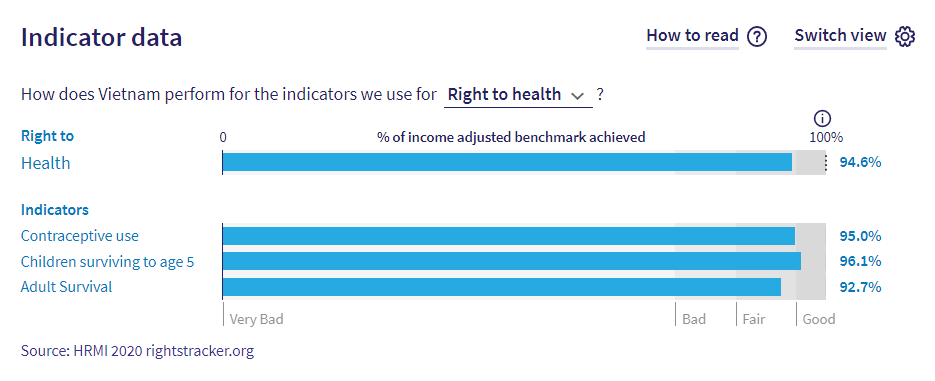

When we line up all low and middle income countries in East Asia and the Pacific in order of their HRMI right to health scores, Vietnam is ranked 3rd out of 23 countries.

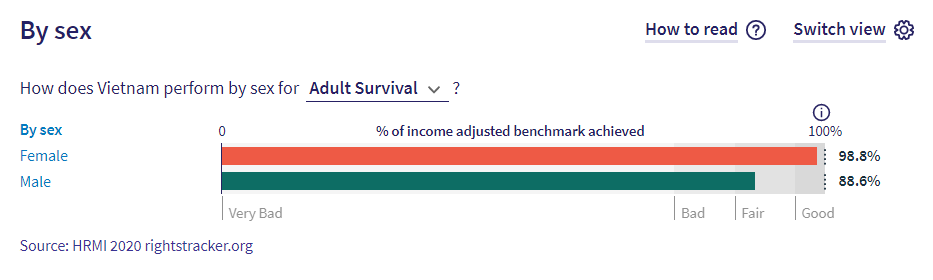

When toggling over the indicator scores by sex on the Rights Tracker, we see that Vietnam females outscore Vietnam males for both the children surviving to age five indicator (97.1% versus 95.2%) and the adult survival indicator (98.8% versus 88.6%).

These right to health indicators collectively relate to SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being, as well as SDG 1: No Poverty.

Right to Housing

Vietnam’s ESR score for the right to housing is 89.5%. As illustrated by the Rights Tracker screenshot below, this score is averaged across two indicators: access to basic sanitation (score = 84.5%), and access to drinking from an improved water source on site (score = 94.5%).

These indicators relate to SDG 1: No Poverty, SDG 6: Clean Water and Sanitation, and SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities.

We asked our expert survey respondents which groups of people they thought were at risk of having each right violated. The following word cloud represents their answers for the right to housing.

Note: The larger the text, the greater the number of human rights experts who identified that group as at risk.

This word cloud shows that 62% of our human rights experts identified people with low social or economic status, and street children or homeless youth, as being particularly at risk of having their right to housing violated.

Right to Work

Vietnam has a score of 91.3% for the right to work, which is the percentage of people who are NOT absolutely poor. Poverty headcount ratio at $3.20 a day is the percentage of the population living on less than $3.20 a day at 2011 international prices. This score takes into account Vietnam’s resources and how well it is using them to make sure its people’s quality of life rights are fulfilled.

The graph below shows that the right to work has improved in Vietnam since 2007:

Civil and political rights

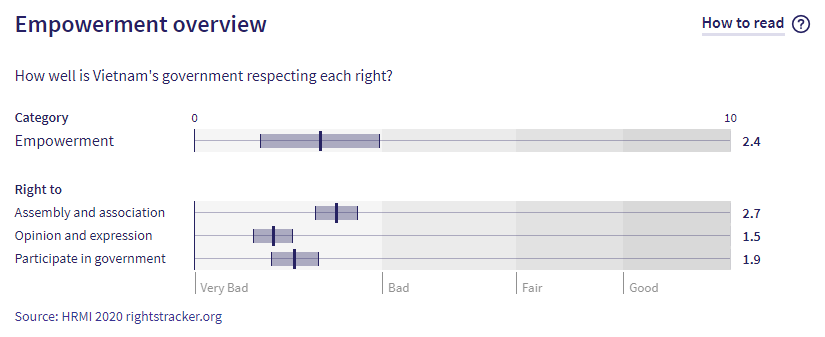

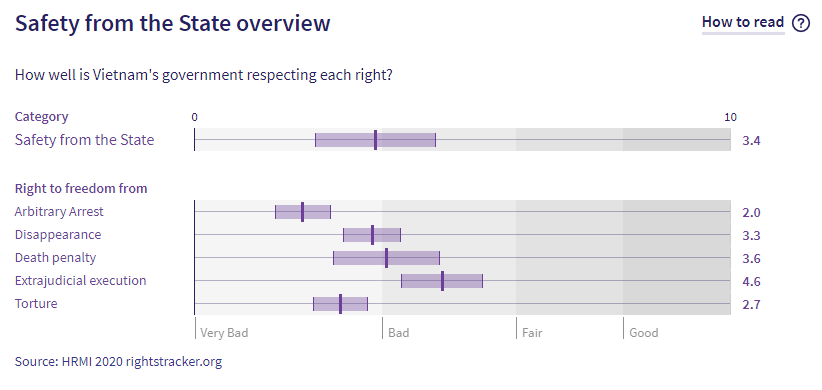

Safety from the State and Empowerment scores (the dark line in the middle of each bar) are presented here with uncertainty bands, showing the credible range of scores, similar to the ‘margin of error’ in opinion polls. The wider the band, the less certain we are of the score, because of a low number of survey respondents, or the wide range of answers they gave, or both. The narrower the band, the more certain we are of the score. For example, the score of 1.5 for the right to opinion and expression could be anywhere between 1.1 and 1.8 — and all of the likely score band falls in the very bad range.

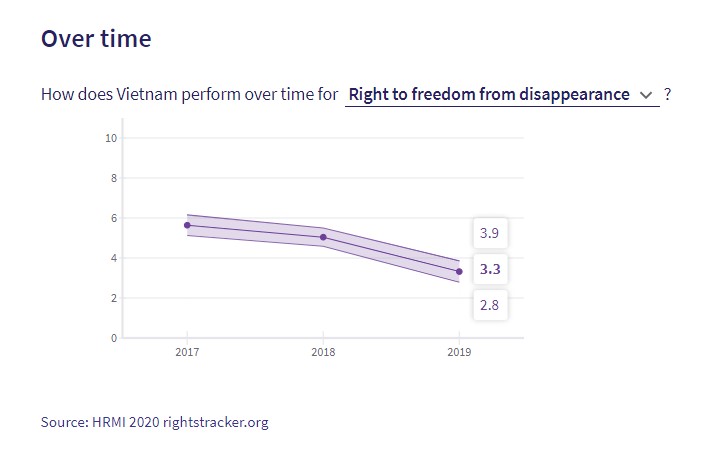

Freedom from disappearance

Vietnam has seen a decline in several of its Safety from the State scores over the past three years, with the freedom from disappearance scores dropping dramatically.

Members of labour unions are at risk for arbitrary arrest

Of the human rights experts interviewed, 100% identified members of labour unions as being particularly at risk of having their right to freedom from arbitrary arrest violated.

93% of our human rights experts identified people engaged in or suspected of political violence as being at risk of having the right to freedom from arbitrary arrest violated. Similarly, 86% of experts identified members of journalists as being especially vulnerable to arbitrary or political arrest and detention by government agents in 2019.

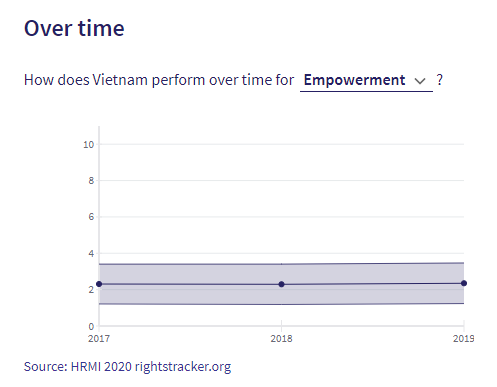

Concerning levels of empowerment in Vietnam, particularly for members of labour unions and journalists

Vietnam’s Empowerment score of 2.4 out of 10 is worse than average than the other 28 countries surveyed and shows no improvement over the last three years.

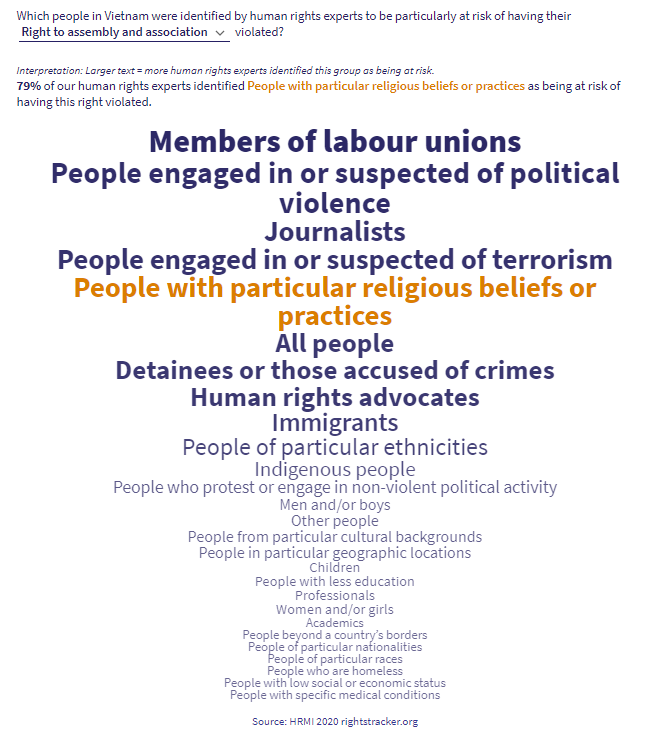

Members of labour unions are most at risk for not being able to enjoy their civil liberties and political freedoms; journalists and people engaged in or suspected of political violence rank second or third for being most at-risk for each metric.

A new cybersecurity law entered into effect in Vietnam in early 2019, despite concern at domestic and international levels. ‘The authorities subjected human rights defenders and activists to harassment, intimidation, and abusive restrictions both online and offline,’ according to Amnesty International. ‘The government prosecuted human rights defenders and activists, using a range of criminal law provisions. Prolonged pre-trial detention was common. Prisoners of conscience were denied access to lawyers and family members, lacked proper health care, and in some cases were subjected to torture.’

People with particular political and religious affiliations suffer from abuses to their safety from the state and their empowerment

Both people with particular political affiliations or beliefs and people with particular religious beliefs or practices suffer from a lack of access to:

- the right to work

- the right to freedom from arbitrary arrest

- the right to freedom from disappearance

- the right to freedom from torture

- the right to assembly and association

- the right to opinion and expression

When asked to provide more context about who was especially vulnerable to restrictions on their rights to assembly and association by the government or its agents in 2019, our respondents mentioned the following:

- Everybody was at significant risk

- Those with certain religious or cultural beliefs, particularly the United Buddhist church adherents of Hoa Hao, Protestants (especially ethnic minorities from Central Highlands) Catholics, and other religious organizations critical of the government or resistant to government control

Immigrants at risk of death penalty

When asked to provide more context about who was especially vulnerable to death penalty executions by government agents in 2019, our respondents mentioned detainees or those accused of crimes, particularly crimes related to murder or drugs.

Immigrants were also identified by 79% of our expert respondents as being especially vulnerable to torture.

See our Rights Tracker for more information on who was identified as being at risk for each quality of life right.

Thanks for your interest in HRMI. To further explore our human rights data for Vietnam, please visit our Rights Tracker, where you can find data by country or right.