Human rights abuses of refugees and asylum seekers in Australia

This country spotlight refers to data published in 2018. For the most recent data, go to our Rights Tracker.

A 12-year-old girl in Nauru who set herself alight is just one of many refugee children there who are suffering from ‘resignation syndrome,’ a form of mental illness where they find life to be without hope and unbearable. As human rights defenders turn the spotlight on Australia’s off-shore detention policies, the Human Rights Measurement Initiative (HRMI)’s new dataset shows how poorly the country is performing in several areas of human rights. Our data put numbers alongside stories coming out of Nauru, showing they are not anomalies, but part of a pattern of human rights violations.

Key findings

The Human Rights Measurement Initiative has measured Australia’s compliance with international law concerning human rights, and compared its performance with 18 other countries.

- Australia scores lower than New Zealand and the United Kingdom on freedom from torture, and freedom from arbitrary arrest.

- Australia’s policy of detaining asylum seekers and refugees in Nauru and Papua New Guinea is a big contributor to these low scores.

- Australia’s treatment of Indigenous people is also an important contributor to its poor scores.

- Australia also performs poorly on the right to freedom of expression and opinion. The recent law forbidding detention staff from reporting on abuses of detainees is probably significant here.

Human Rights Abuses of Refugees and Asylum Seekers

Zahra prays for rain so she can wash her babies in clean water (we have changed names in this reporting). When her first baby was born, there was only six hours of running water at the Australian-run detention camp she lived in, and you couldn’t drink it. She is now an official United Nations refugee, having feared for her life in her home country, but she and her family are still detained on Nauru – just a bit further down the road, without the guards. Water is still unreliable and undrinkable. She’s lived here for five years. Maryam was the first woman to give birth as a detainee in Nauru, sent there by the Australian government, under their policy of not accepting asylum-seekers who arrive at Australian island territories. “They told me everything would be safe for my baby,” she says. “When I gave birth in the labour ward there was a dog under my bed.”

Maryam and her husband fled Iran six years ago, with other members of their family, and have recently been recognised as refugees by the United Nations. When the Australian government intercepted the boat they were travelling on, everyone else on the boat was taken to Australia, but Maryam and her husband were sent to Nauru. Children are missing out on education, and even on the basic necessity of play. “Here there is nowhere for me to take my daughter to play and have fun,” Maryam says. “She does not even know what a park is like, because she has never seen one.” You can read more of Zahra’s and Maryam’s stories in this interview.

Most Australians are probably aware of some of the conditions refugees and asylum seekers endure in Nauru and Papua New Guinea. Some may have heard the stories of torture and abuse of teenagers in the Australian prison system that have emerged over recent years. People may assume that these are rare examples of human rights violations by a developed country. But HRMI’s new dataset, freely available to download, suggests that Australia’s human rights challenges are more significant than people may realise. Since 2013 the Australian government has operated a policy of refusing to allow settlement of any refugees attempting to reach Australia by boat. Instead, refugees and asylum seekers are routinely sent to Nauru and Papua New Guinea where they are at risk of violence. They also have restricted access to food, medical care, and sanitation, and have not been issued with local documentation, which means their freedom of movement within those countries is restricted.

Asylum seekers caught by Australia’s policy have many of their rights under international law infringed. They are subject to arbitrary arrest and detention; their freedom of movement is restricted; and for many, the conditions in which they are held amounts to torture or ill-treatment.

While the refugees and asylum seekers in those facilities in Nauru and Papua New Guinea are under the control of those governments, the UN Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, has stated that “Australia bears responsibility for the treatment of immigrants and asylum seekers in those centres”.

This is because they are being held there for the sole purpose of implementing Australia’s policies of intervention in the high seas and discouragement of asylum seekers.

As national and international pressure builds on Australia to end the indefinite detention of around 2000 refugees and asylum seekers currently confined to Nauru and Papua New Guinea, HRMI’s ground-breaking data can help quantify how Australia’s immigration policies are stopping the country from fulfilling its international human rights obligations.

Here’s what our data show.

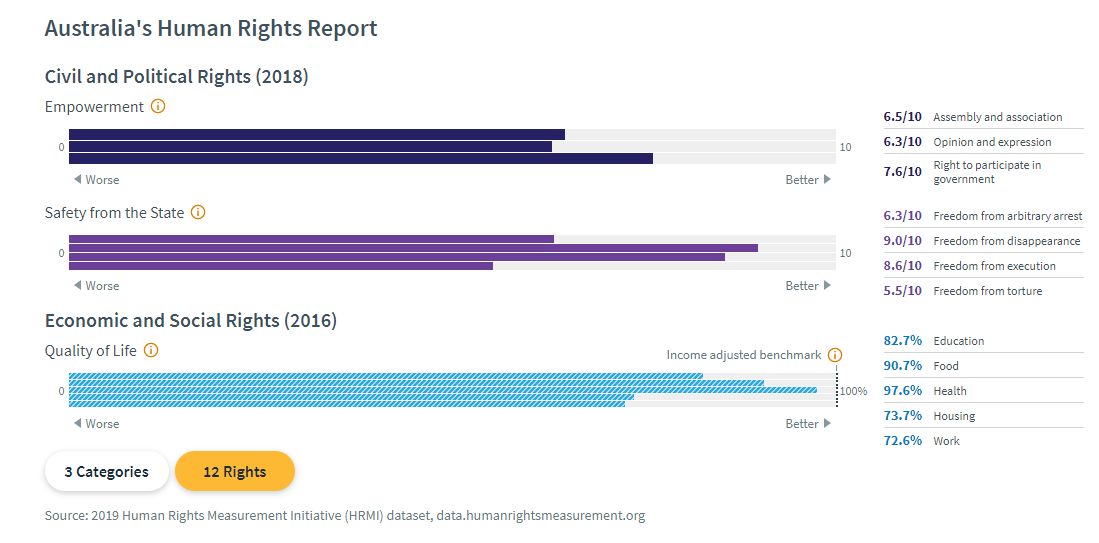

The chart below summarises Australia’s performance across 12 human rights. In this chart, each row represents a right. The longer the length of the bar, the higher the country’s score is, the better the performance of the country on that human right.

Scores for the seven civil and political human rights are divided into two sub-sections: Empowerment and Safety from the State (both sections in different shades of purple). The scores for the five economic and social human rights are categorized under a subsection titled Quality of Life (this section in a shade of blue).

Australia scores 5.5 out of 10 for freedom from torture

Let’s dig into this in more detail, starting with Australia’s performance on the right to freedom from torture and ill-treatment, which is scored 5.5/10, and on the right to freedom from arbitrary arrest, where Australia scores 6.3/10.

There are no objective statistics on things like torture because torture and ill-treatment tend to take place in secret or be framed in other terms. To circumvent this problem, we surveyed human rights experts in Australia and calculated scores based on the information they provided.

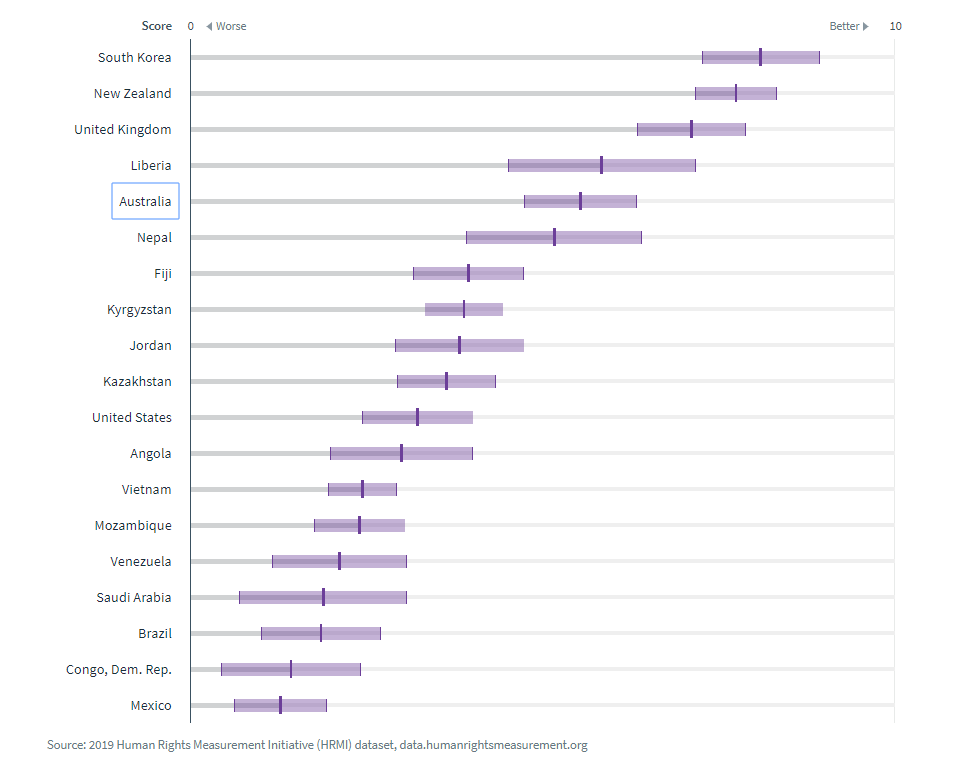

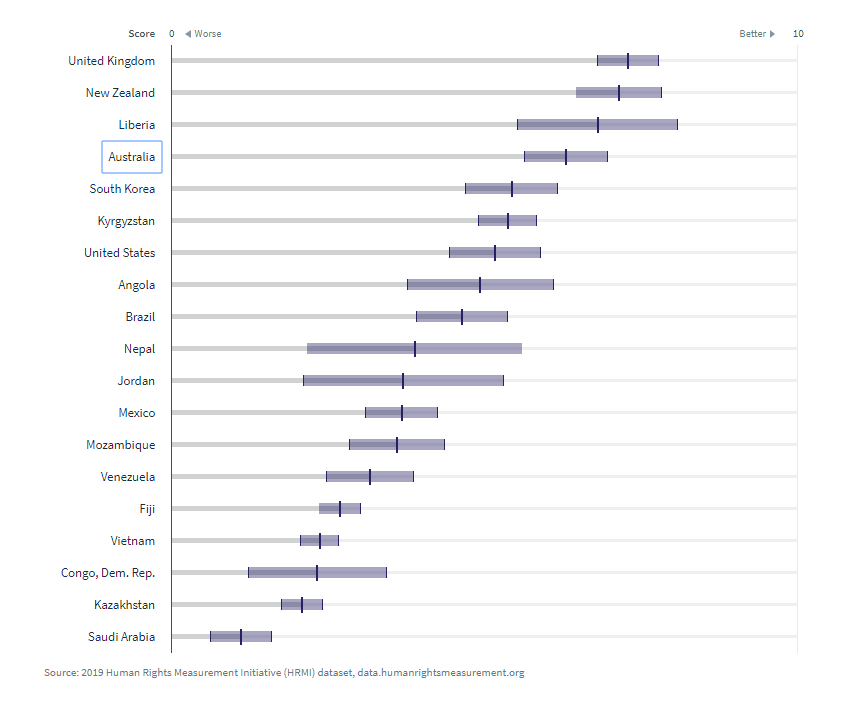

In the chart below, Australia’s performance on this human right is compared with that of the 18 other countries in our survey of civil and political rights. The two other high-income OECD countries we have data for so far are New Zealand, South Korea, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The chart below suggests that Australia’s performance on the right to freedom from torture and ill-treatment is worse than South Korea, New Zealand, and the UK, and better than the US.

We draw this conclusion from the fact that there is no overlap of the purple bars for Australia and those other countries – the bar representing Australia’s score is trailing behind the bars for the United Kingdom and New Zealand. Instead, Australia’s performance is more in line with countries such as Liberia and Nepal, as indicated by the fact that there is a substantial overlap of the purple bars for these countries.

A number of things are driving this result – notably Australia’s mandatory and prolonged detention of people, including children, who are refugees or who are seeking asylum in Australia.

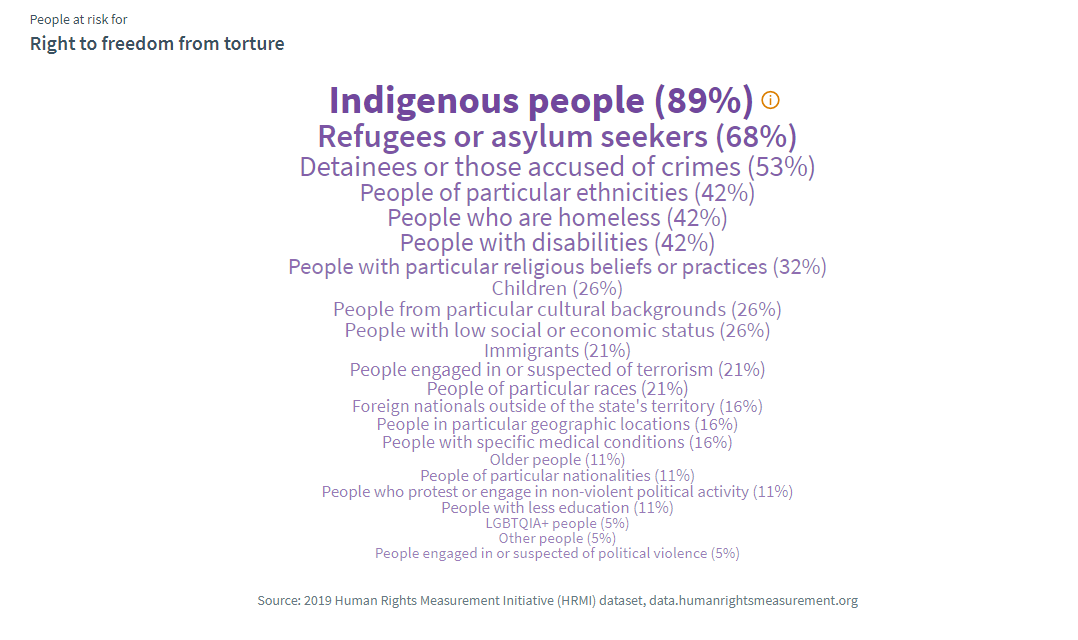

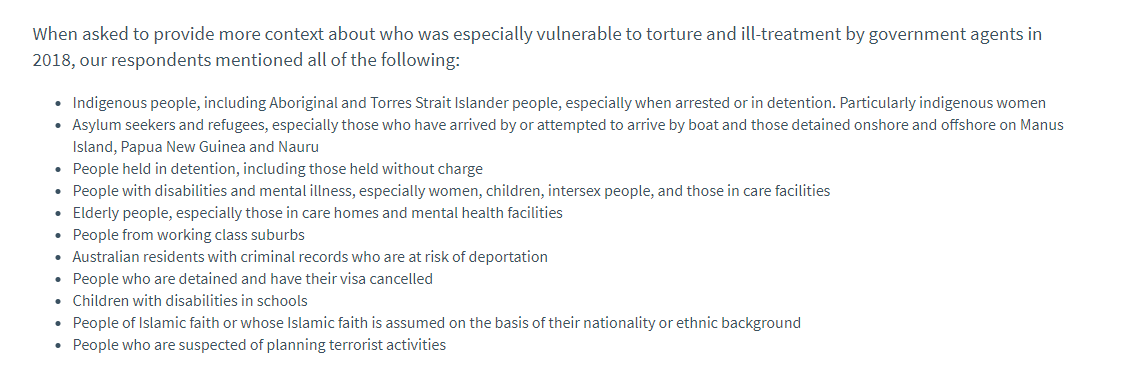

Australia’s ill-treatment of refugees and asylum-seekers is a large contributor to its poor score on the right to freedom from torture. We asked our respondents which groups were particularly at risk of torture and ill-treatment in Australia. We have illustrated their answers using the word cloud below, where the size of the font shows how many respondents indicated the group concerned was especially vulnerable. In this case, 68% of our respondents selected refugees and asylum seekers as a group particularly at risk of torture or ill-treatment in Australia. If you visit this chart on our data visualisation website, you can find this word cloud and similar charts for every other right we measure.

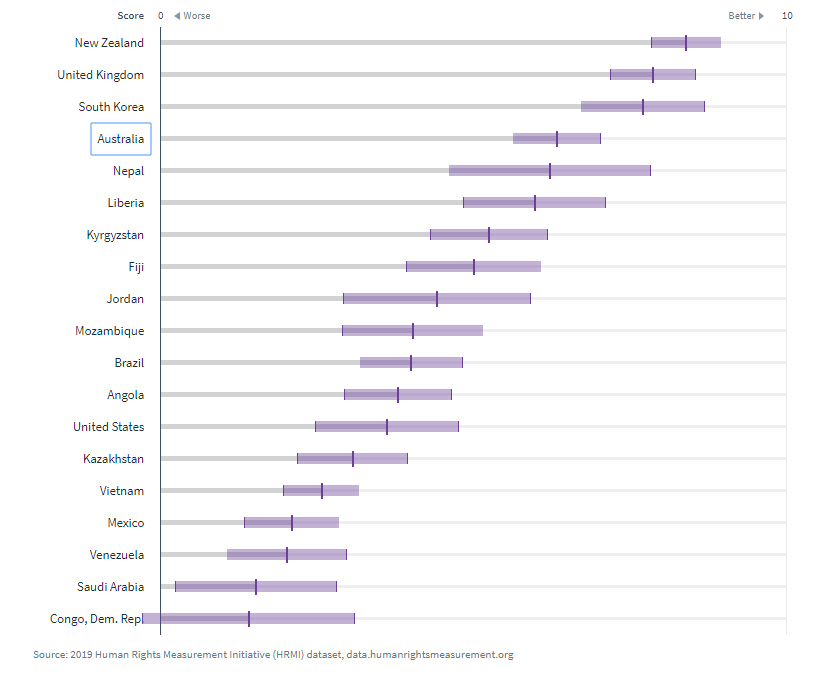

All asylum seekers and refugees being held in Nauru and Papua New Guinea can argue that their right to be free from arbitrary arrest and detention is being breached. We see in the comparison chart of the 19 countries on this right, that Australia performs worse than New Zealand and the United Kingdom on this right also, and most likely worse than South Korea. You can explore this right further on our data site.

Freedom of expression and opinion

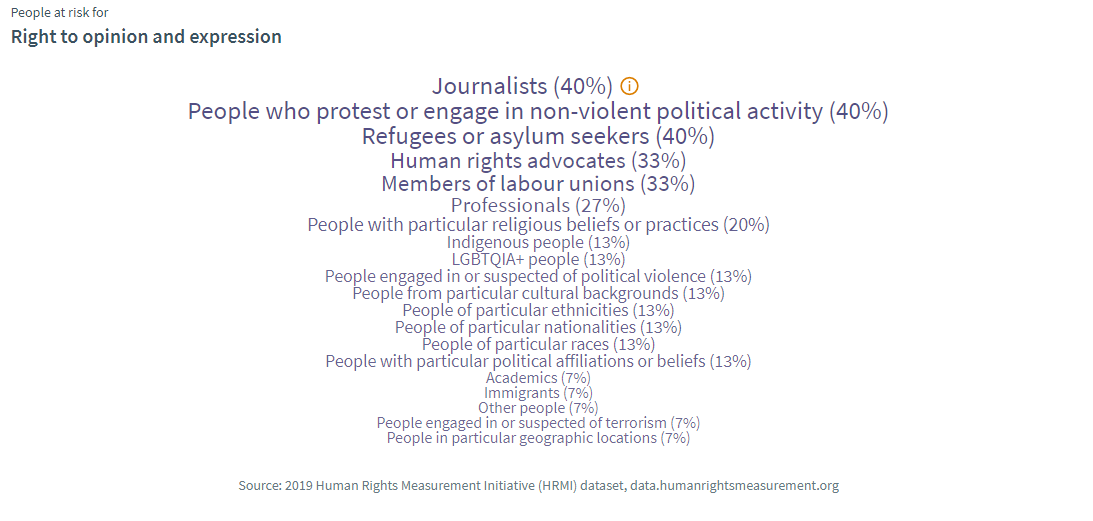

Australia’s recent decision not to allow Chelsea Manning into the country on her speaking tour is something that may affect its scores on freedom of expression and opinion in our next survey. However, in the current data, which captures the situation in 2018, you can see in the chart at the top of this article that Australia’s score on this human right is 6.3/10. One recent law that may have influenced this score is the Australian Border Force Act 2015 that made it a crime for offshore detention workers (except medical staff) to reveal abuses committed against asylum seekers. The word cloud for this right shows that journalists and human rights activists are among the groups our respondents said were at most risk of having their freedom of expression infringed upon. This is particularly concerning when combined with our other findings: there are significant human rights problems in Australia and the Australian people deserve to hear about them.

Looking ahead, there are concerns that Australia’s performance in the area of freedom of opinion and expression could slip further. The recently passed Espionage and Foreign Interference Act and Electoral Legislation Amendment (Electoral Funding and Disclosure Reform) Act threaten to further impede the work of journalists, whistleblowers, human rights activists, charities, and others working to share information in the public interest.

Looking ahead, there are concerns that Australia’s performance in the area of freedom of opinion and expression could slip further. The recently passed Espionage and Foreign Interference Act and Electoral Legislation Amendment (Electoral Funding and Disclosure Reform) Act threaten to further impede the work of journalists, whistleblowers, human rights activists, charities, and others working to share information in the public interest.

HRMI’s comparison of 19 countries’ performance on this human right is illustrated in the chart below. While Australia’s performance is above that of most countries in the survey, New Zealand and the United Kingdom do better.

Australia’s treatment of Indigenous people is also an important contributor to its poor human rights performance. You can read more about this aspect of our findings in our article here. Overall, the rights of Indigenous people and those seeking asylum in Australia feature prominently amongst Australia’s human rights concerns – in Human Rights Measurement Initiative data, in the media, and in social conscience. These are just some of the stories our data tell. Please explore the data portal yourself – by country, or by right – and let us know what you think.