The future of human rights in Brazil

This country spotlight refers to data published in 2019. For the most recent data, go to our Rights Tracker.

The 2018 Brazilian Election

Brazil is the latest country to be swept up by the international wave of far-right political success.

On October 28th, Brazil elected the former military captain Jair Bolsonaro as its President; a major shift from the previous centrist government. With over 60,000 people slain in 2017, Brazil is already one of the most violent countries in the world. Bolsonaro’s campaign speeches were often racist, misogynistic and homophobic. His hostile stances on many issues could lead to policies that cause many Brazilians to suffer more.

Before Bolsonaro was elected, ESCR reported:

Multiple ESCR-Net members, human rights organizations and social movements in Brazil and beyond have raised serious concerns following the election far-right of retired military officer Jair Bolsonaro to head the world’s fourth-largest democracy.

The groups cite statements made by president-elect Bolsonaro during his campaign that revealed a threatening stance towards democratic freedoms, including a promise to dismantle a series of hard-won public policies that guarantee the country’s compliance with internationally recognized human rights standards.

According to Conectas Direitos Humanos, among his most troubling positions is a plan presented to the TSE (High Electoral Court) that outlined a punitive approach to public security. Bolsonaro has already encouraged increased use of firearms by civilians and has indicated he is in favor of reducing the age for trying youth as adults, imposing harsher prison sentences and empowering the police to employ deadly force with impunity. Human rights advocates argue that these policies, “have a very clear target – black youths living in underprivileged areas.”

[Read more at ESCR-Net].

What HRMI data on Brazil show

In 2019, the Human Rights Measurement Initiative conducted a 19-country survey measuring civil and political rights performance. Brazil was one of those countries, so HRMI has extensive data on these rights, including data relevant to the views expressed by Bolsonaro, such as vulnerability to the death penalty and extrajudicial killings, as well as actions committed against Brazilians by state actors.

These data paint a bleak picture in the context of the Bolsonaro presidency. Brazil is a part of BRICS, a group of national emerging economies who are experiencing high economic growth rates. Except in recent years, Brazil’s GDP growth has been quite high, reaching over 8% growth in 2010. Economic opportunity has disproportionately shifted the government’s focus to economic success. As a result, some of the country’s civil and political rights development has lagged.

Brazil performs poorly in safety from the state

On the HRMI data website, you can view our data by country or by right. Exploring by country will allow you to see all of our measurements in detail with regards to that specific country. Viewing the data by right will compare all of the survey countries’ performances with respect to a certain right.

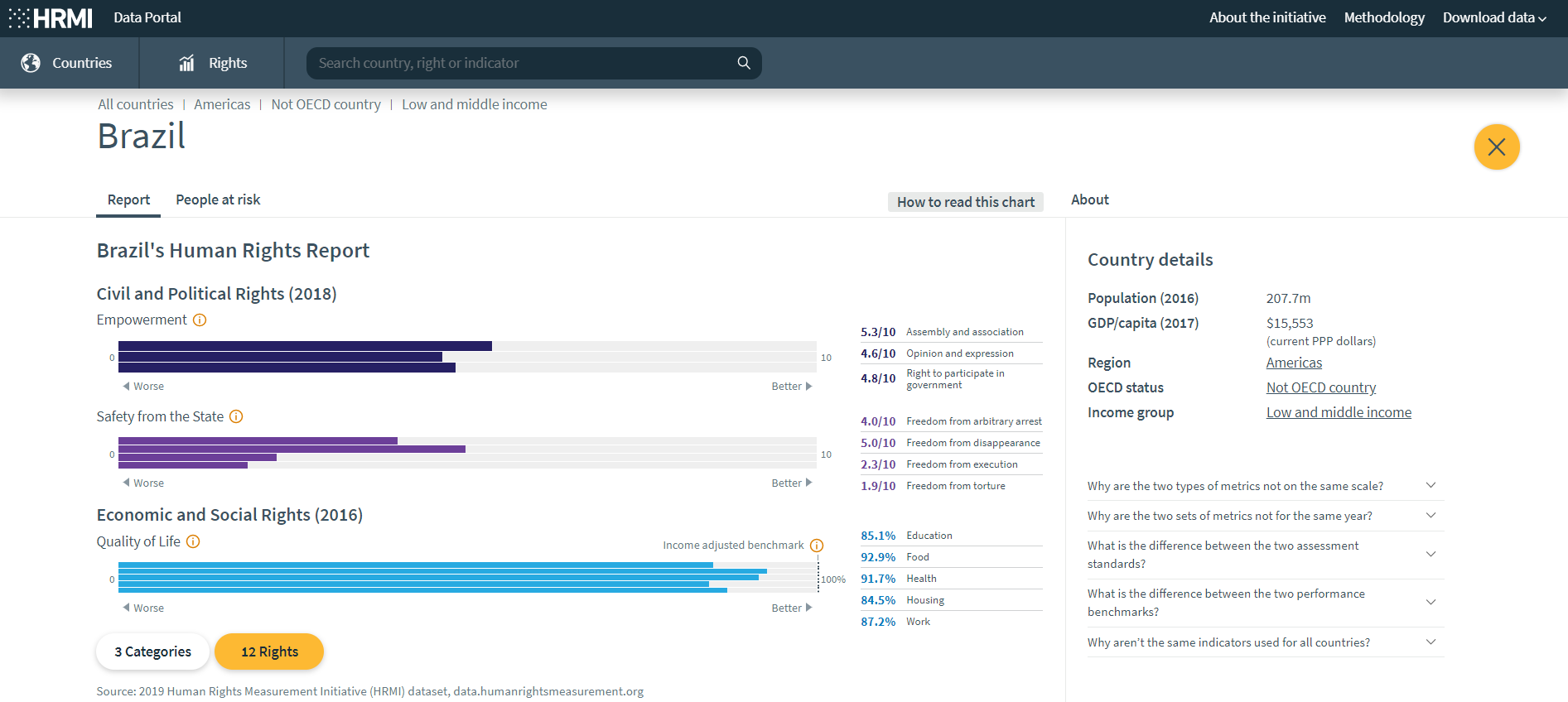

On the website’s home page, you can view all of the countries in the survey and then if you click on Brazil (as in the image below) you can see an overview of Brazil’s 12 Human Rights scores.

While Brazil does perform comparatively well in providing access to food, education and work to its citizens, it is one of the worst performers with respect to physical safety from the state.

These ‘physical integrity’ rights include the rights to freedom from disappearance, arbitrary arrest, execution and torture—all of which are now at more risk if President Bolsonaro carries out his stated goals.

Freedom from execution in Brazil

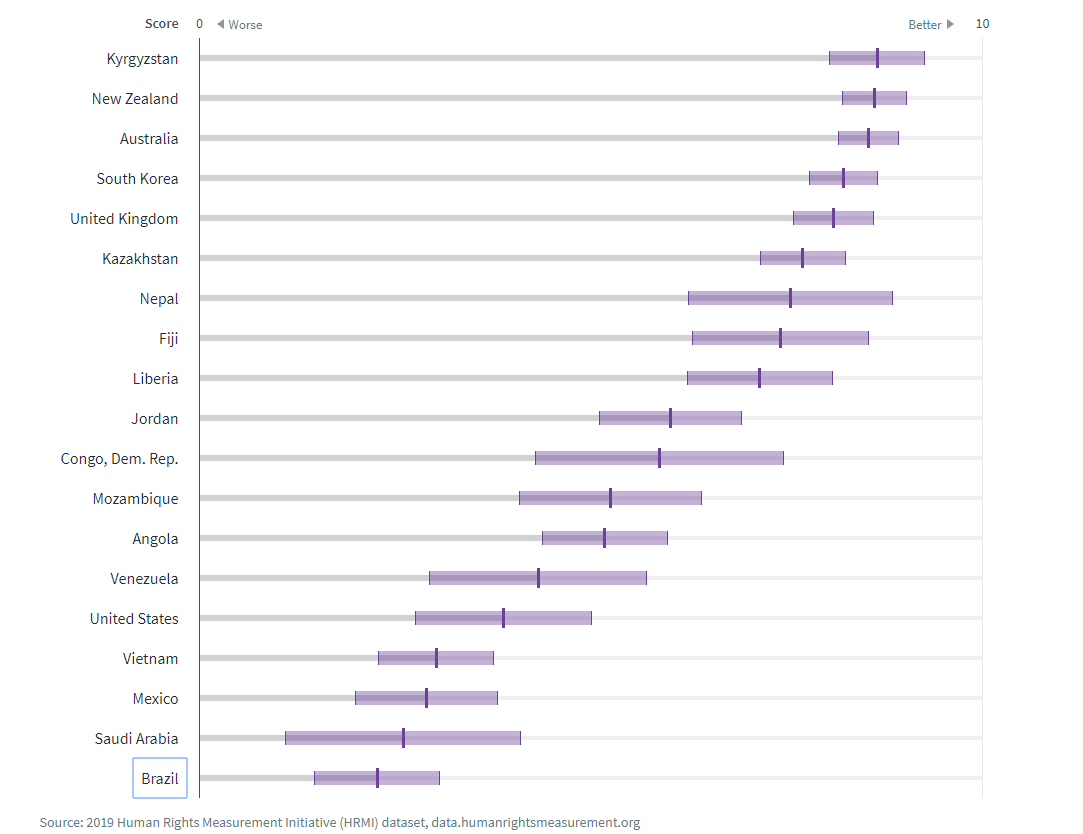

Among our survey countries, Brazil ranks at the bottom (19th out of 19) on how safe its citizens are from execution. In our metrics, the right to freedom from execution includes freedom from both extrajudicial killings and death penalty executions.

Under current Brazilian law, the death penalty is virtually abolished, last used in 1876, though executions are still legal during wartime. So it is extrajudicial killings that threaten freedom from execution.

In 2016, police officers killed 4,226 people, a 26% increase from the year before. Some of these cases are well documented, but many are not, and proper prosecutions are not carried out.

If Bolsonaro brings back the death penalty and an execution is carried out, Brazil would be in violation of international law.

In 2002, Brazil ratified the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, agreeing to not use the death penalty. There is no provision for the reinstatement of the death penalty. Once a country has ratified the document, they cannot revoke their commitment to its provisions. However, Bolsonaro is a staunch proponent of restarting the death penalty in Brazil. That means that if Bolsonaro brings back the death penalty and an execution is carried out, Brazil would be in violation of international law.

President Bolsonaro has also promised to shield police from punishment when they kill someone. Instead of being tried in civilian court as international law demands, police officers on trial for extrajudicial killings are already being tried in military court.

Without a fair trial system, Brazilian police who execute civilians are not prosecuted effectively. Victims do not receive the justice they deserve. If the death penalty is reinstated and Bolsonaro relaxes police standards, then Brazil—already one of the poorest performers in the right to freedom from execution—could see its performance become even worse.

Freedom to Opinion and Expression in Brazil

Brazilians are also facing limits on their ability to express themselves freely. HRMI data show that Brazil currently performs only averagely compared to the other survey countries with respect to freedom to opinion and expression. The government is already acting to increase restriction of this right.

There are reports of police raiding over 20 universities in what appears to be an attack on Brazilian academia. Specifically, academics have been subjected to ‘invasions by military police; the confiscation of teaching materials on ideological grounds; and the suppression of freedom of speech and expression, especially in relation to anti-fascist history and activism’.

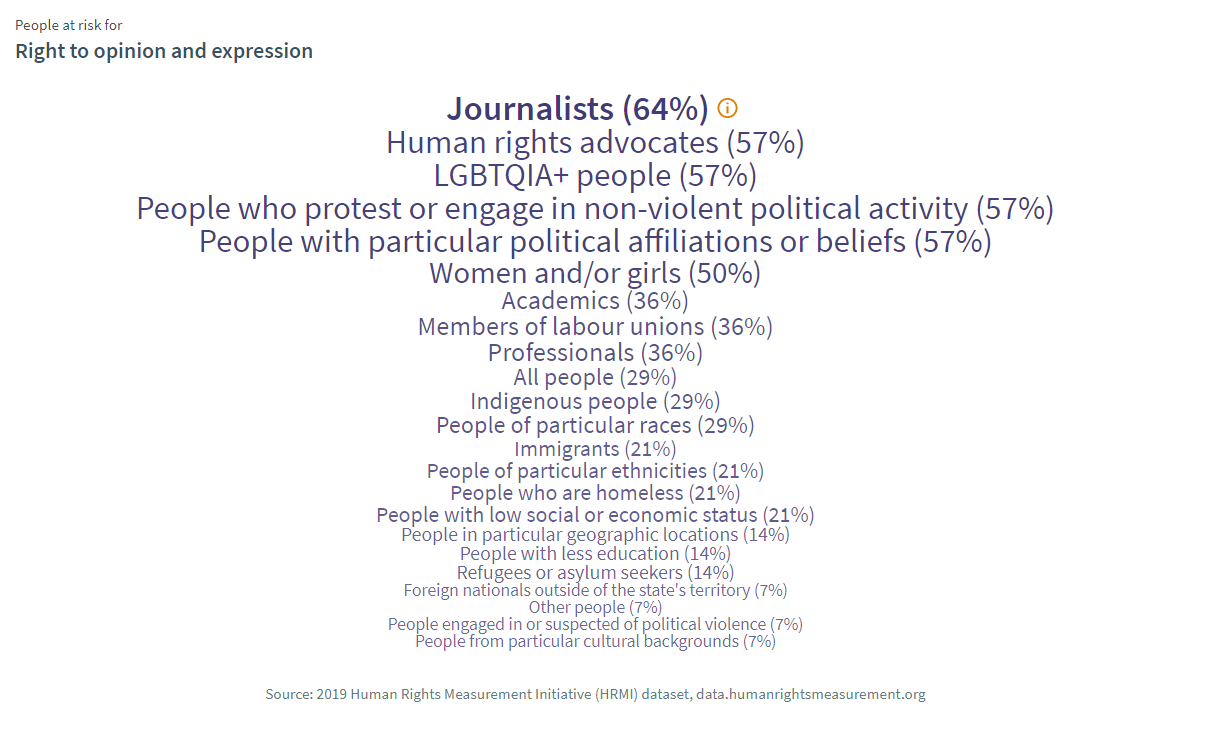

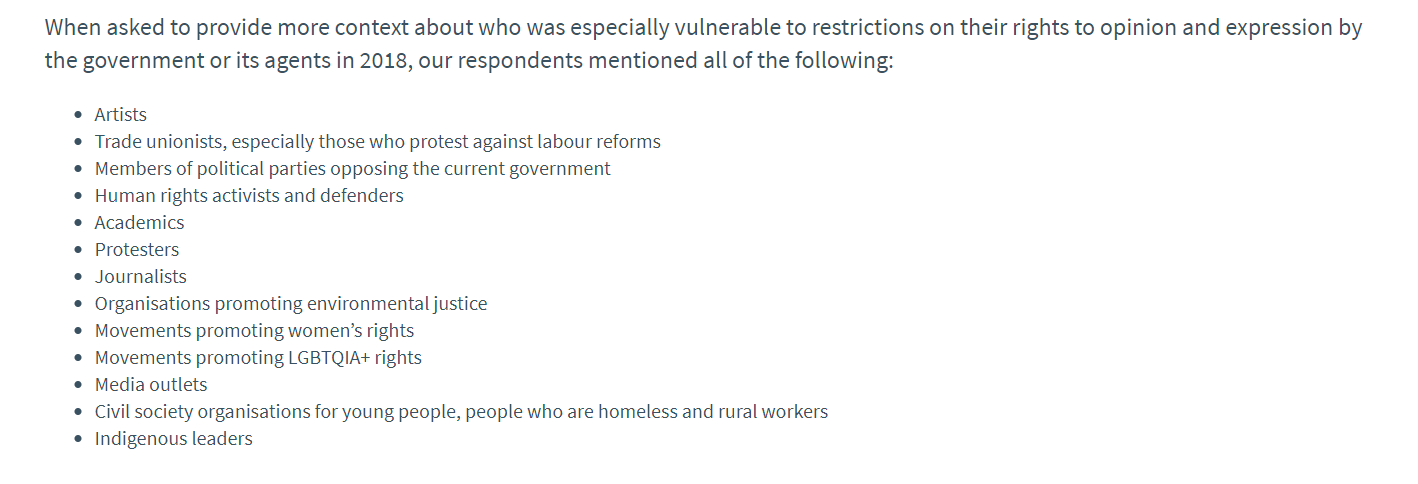

The word cloud pictured below shows the groups most at risk in Brazil for having their right to the freedom of expression violated.

Our data show that academics are already a high-risk group for having their freedom of expression inhibited. HRMI’s word cloud on the groups most of risk for freedom of expression violations also suggests that academics who are human rights advocates may be at heightened risk.

Expression that is not actually illegal is being obstructed. President Bolsonaro has been direct in voicing admiration for the military regime of the mid-20th century. A return to the law and order Brazil of that authoritarian government is on the horizon with this type of government intrusion.

How HRMI data can improve human rights in Brazil

HRMI data provide motivation to act, enabling countries to reflect on their human rights performance. HRMI data also make it possible to hold all countries accountable for their human rights performance.

HRMI data allow us to see that Brazil’s human rights performance is poor and has the potential to become worse. Having access to unbiased data creates an environment where facts can be the source of dialogue. HRMI data is a useful tool that anyone can use to start conversation. Brazilians who have access to HRMI information will be better equipped to recognize its government’s human rights abuses. As a result, Brazilians may be more likely to elect public officials whose focus is on improving human rights. A data-oriented approach to public policy reinforces trust in governmental institutions.

Using HRMI, President Bolsonaro and the Brazilian government can be pressed to create a better world for its people.

Who can use these data?

All of HRMI’s data are freely available to anyone. You can explore our data site here, and even download the dataset.

We have data on seven civil and political rights: as well as five economic and social rights.

HRMI aims to produce useful data. Some of the people we expect will use our data are:

- Journalists, especially those reporting a particular country, and those focusing on human rights, politics, social issues or international affairs

- Researchers

- Government policy advisers

- Human rights advocates

- NGOs

- Human rights monitors within a region, and at the international level

- Companies, for decision-making, to minimise risk for investors, and direct capital flows ethically.

If you know anyone in those categories, please let them know about HRMI, in case our data can be useful to them.

HRMI’s data have been available for only a few months so far, but as different people use them, we want to share stories and case studies. Whenever you see our data in action, please tell us, and we’ll include a link on our website.