Reforms needed to reduce relative poverty in South Korea

이 글은 한국어로도 읽을 수 있습니다. 언어를 변경하려면 위의 드롭다운 메뉴를 사용하세요.

By HRMI researcher Paddy Baylis

The Human Rights Measurement Initiative (HRMI) is the first global initiative to track the human rights performances of countries. This country profile focuses on the economic and social rights outcomes for South Korea. All data discussed below are available on our Rights Tracker. See also HRMI’s Research credentials. You are welcome to use and quote from this article with attribution. This country spotlight refers to data published in 2020.

Reforms needed to reduce relative poverty in South Korea

Following the Korean War in 1950-1953, South Korea (Republic of Korea) has been a world leader in economic growth, recording the fastest rise in GDP per capita (national income) of any country in the world from 1980-1990. This has led to a significant reduction in poverty and a huge rise in education and infrastructure. South Korea is now the 12th largest economy in the world and is extremely highly ranked in terms of healthcare and education.

Despite these successes, South Korea has high rates of relative poverty especially in senior citizens. It currently sits in the bottom 3 OECD countries in terms of relative poverty rate and is by far the worst in the OECD for relative poverty rate for people aged 65+.

One reason for this is a lack of welfare spending. Despite significant economic success, social spending is extremely low in South Korea at 10.4% of GDP compared with an OECD average of 21.6%. This is the lowest of any country in the OECD.

Additionally, South Korea has a dualistic economy with significant productivity gaps between regular and non-regular workers, and small and large businesses. This dualistic nature is also reinforced by legislation that encourages firms to hire non-regular temporary workers in order to avoid layoff costs.

However, these issues are being addressed. South Korea’s social spending as a proportion of GDP has quadrupled from 1990-2015. Since election in 2017, the current administration led by President Moon Jae-In has drastically increased budgets for welfare as well as introducing significant pro-labor reforms including a raised minimum wage.

Continued reforms should allow South Korea to bring its human rights scores impacted by poverty in line with the other human rights that it is successfully respecting.

The Human Rights Measurement Initiative (HRMI) uses award-winning methods to learn what improvements are possible within a country’s limited income. Some headlines from this article:

- If South Korea were to operate at its full potential, over 1 million additional people would enjoy food security.

- If South Korea were operating at best practice, an additional 10,000 children would be born at a healthy weight each year.

- If South Korea was operating at its full potential, 6.5 million people would be lifted out of relative poverty.

- If South Korea were operating at best practice, an additional 75,000 secondary school aged children would be enrolled in secondary school.

Let’s explore the economic and social rights performance of South Korea using HRMI’s ESR data.

The population of South Korea in 2017 was 51.5 million, at which time South Korea had a GDP per capita of $35,938 (in 2011 PPP dollars). Therefore, HRMI ESR metrics for South Korea are best assessed against the income adjusted performance benchmark using the high income assessment standard.

Right to Food

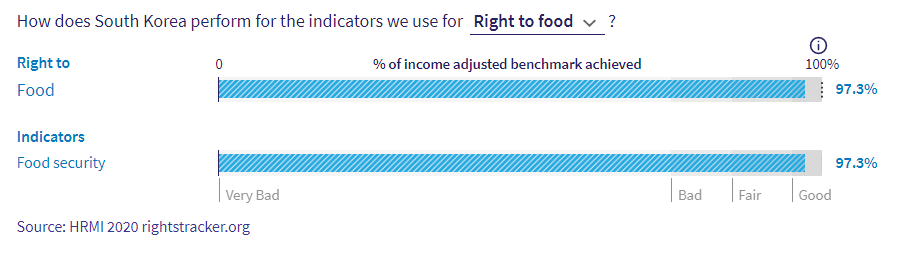

South Korea scored 97.3% on the right to food, which is based on the percentage of the population that is food secure.

We use food security as a high-level ‘bellwether’ indicator to reveal how many South Koreans have adequate access to food. (For more on this, please see our Methodology Handbook.)

This score means that South Korea is doing 97.3% of what should be possible with its current GDP per capita to ensure the enjoyment of the right to food. When combining this score with population statistics, HRMI data tell us that:

If South Korea were to operate at its full potential, over 1 million additional people would enjoy food security.

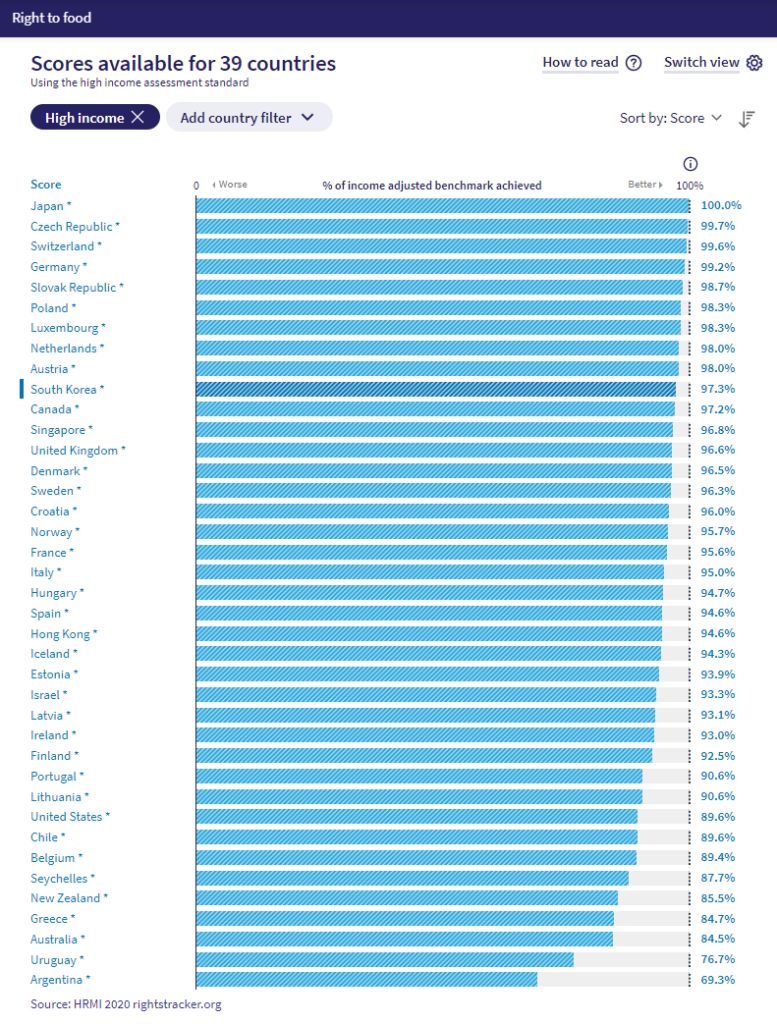

HRMI’s Right Tracker allows us to compare rights scores across countries or groups of countries. As shown below, when comparing right to food scores across high income countries, we can see that South Korea is in the upper middle range.

This graph tells us that while South Korean policy-makers are doing a good job in terms of securing people’s right to food, they could look to other high income countries who are doing marginally better (for example, Japan, Czech Republic and Switzerland) for examples of ways to potentially make improvements.

Right to Health

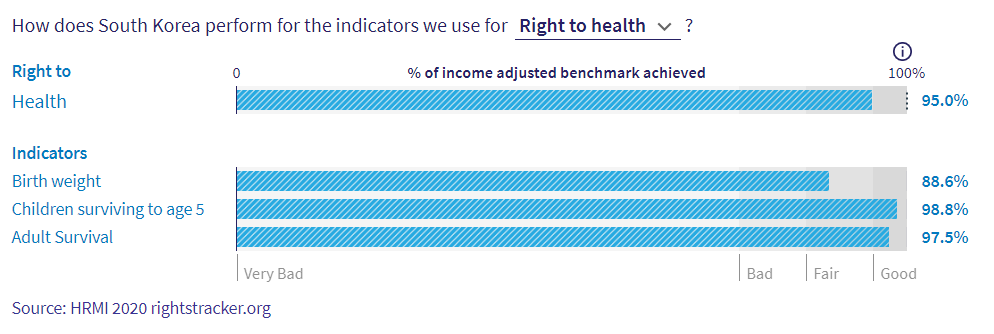

South Korea scores 95.0% on the right to health.

As shown in the image below, this score comes from three indicators: the percentage of infants who are not low birth weight (score = 88.6%); children surviving to age five (score = 98.8%); and adult survival (score = 97.5%).

On average, these scores tell us that the extent to which South Koreans enjoy the right to health is 95.0% as high as it could be given South Korea’s current income level.

Significantly, when we line up all high income countries in order of their right to health HRMI scores, South Korea is ranked 6th out of 52. However, in terms of babies born not at a low birthweight, South Korea ranks 17th out of 52. Here South Korean policy-makers could look to better performing high income countries for examples of ways to make improvements for birthweight outcomes. In the case of babies not born low birthweight, the top ranked high-income countries are Iceland, Estonia, and Latvia.

Data are available for South Korea’s right to health score each year from 2007 to 2017. Therefore, we can use the Rights Tracker over time graph to observe any trend in right to work outcomes for South Koreans over a ten year period.

We can see that Right to Health has stayed relatively constant around the 95% mark over the 10 years from 2007-2017.

If South Korea were operating at best practice, an additional 10,000 children would be born at a healthy weight each year.

Right to Work

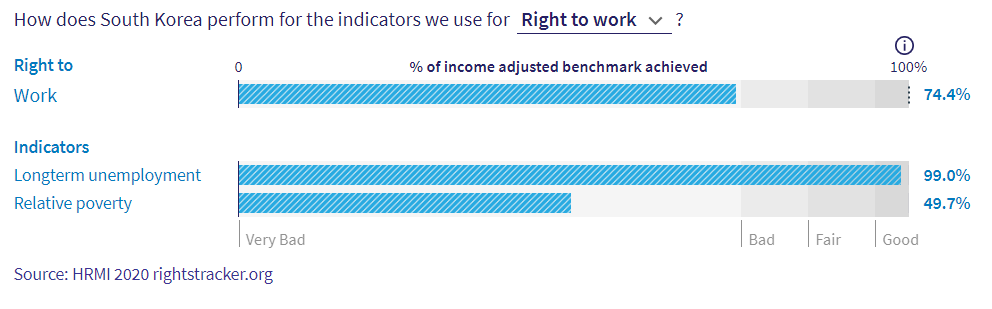

South Korea has a score of 74.4% for the right to work. This means South Korea is only achieving 74.4% of what is possible with its current income in terms of ensuring the right to work.

74.4% is a poor score but it is based on two different indicators – the percentage of the unemployment population who are not long-term unemployed and the percentage of the population that is not in relative poverty. The difference between these indicators for South Korea is enormous as shown below.

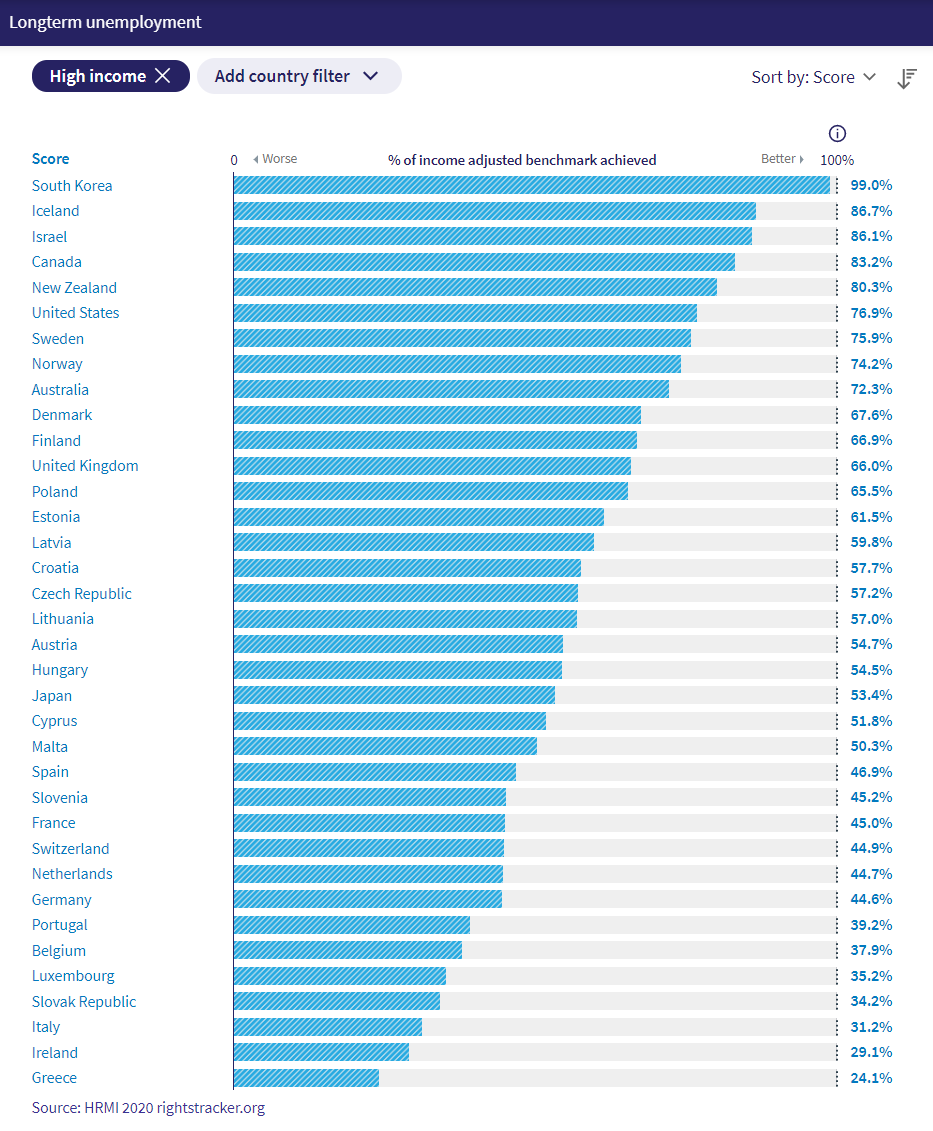

Long-term unemployment is defined as the number of people with continuous periods of unemployment extending for 12 months or longer, expressed as a percentage of the total unemployed population. The score for South Korea for this indicator is 99.0% which is an excellent score – as shown in the image below it is by far the best score in the world.

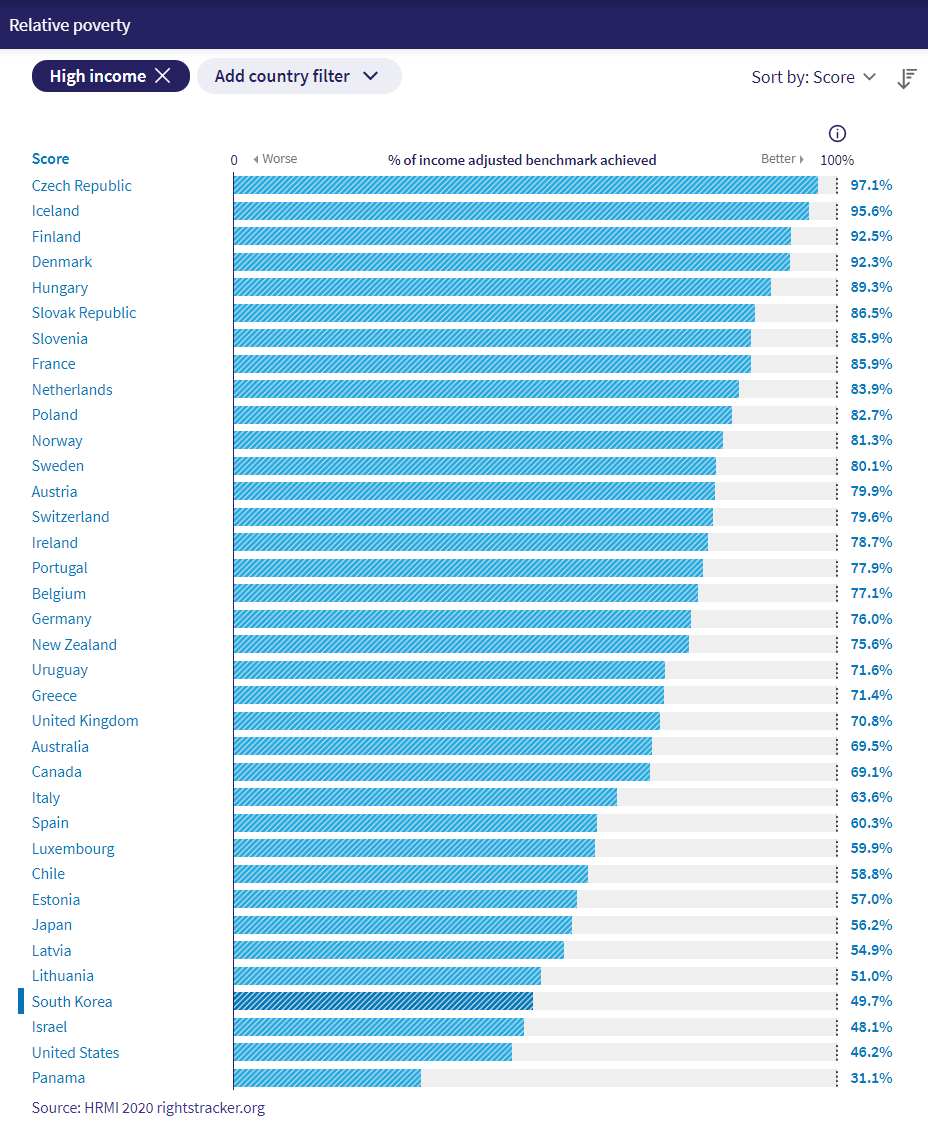

The second indicator is the percentage of the population that is not in relative poverty. Relative poverty is based on the equivalised disposable household income concept and is defined as having an income less than 50% of the median income. Here South Korea scores just 49.7%. This score is inexcusably bad.

Data are available for South Korea’s right to work score each year from 2007 to 2017. Therefore, we can use the Rights Tracker over time graph to observe any trend in right to work outcomes for South Koreans over a ten year period.

As we can see, South Korea has actively regressed in terms of right to work since 2007 largely thanks to an increase in the relative poverty rate.

If South Korea was operating at its full potential, 6.5 million people would be lifted out of relative poverty.

Right to Education

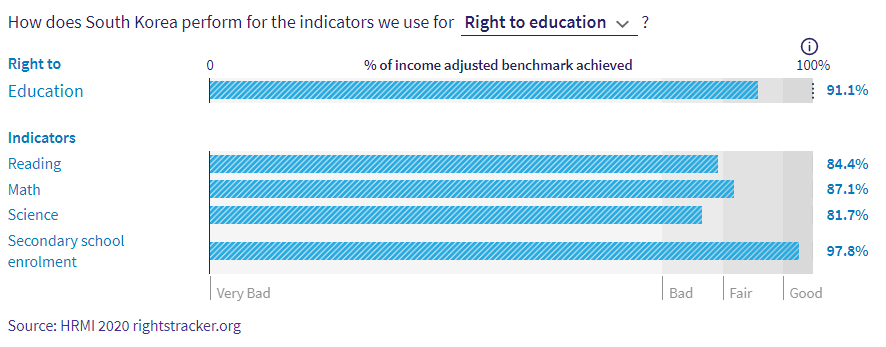

HRMI uses four indicators under the high income assessment standard for the right to education. The first three indicators reflect the percentage of students achieving level 3 or better on math, science and reading PISA tests. The fourth indicator is the net secondary school enrollment rate. HRMI’s overall right to education score is computed by first calculating income adjusted scores for the three PISA tests and then taking the average. This result is then averaged with the country’s secondary education score.

As shown on the Rights Tracker image, South Korea’s income adjusted scores on the PISA reading, math and science tests are 84.4%, 87.1%, and 81.7%, respectively. The average PISA score is therefore 84.4%. When combining this PISA average with the secondary school enrollment score of 97.8%, South Korea gets an overall right to education score of 91.1%.

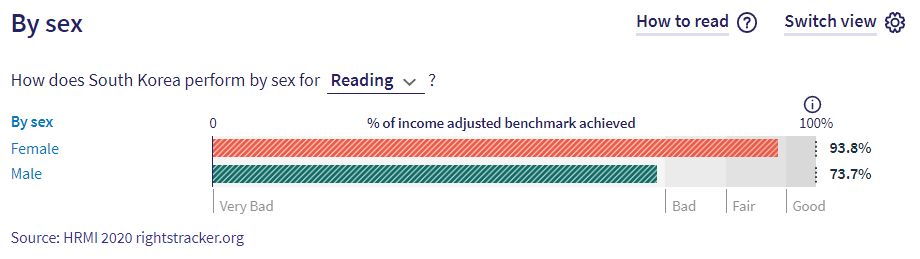

Data are also available for comparing right to education indicator scores between females and males. As seen in the screenshot below, South Korean females have significantly better PISA reading scores than South Korean males (93.8% versus 73.7%). They also perform better in science and math (85.6% v 78.2% and 90.4% v 84.0% respectively).

If South Korea were operating at best practice, an additional 75,000 secondary school aged children would be enrolled in secondary school.

Thanks for your interest in HRMI. To further explore our human rights data for South Korea, please visit our Rights Tracker, where you can find data by country or right.