2020: the human rights situation in Brazil

As the first global initiative to track the human rights performances of countries, the Human Rights Measurement Initiative (HRMI) provides both civil and political rights and economic and social rights scores for Brazil, and many other countries. All our data are available on our Rights Tracker. Read about our research credentials here.

This country spotlight refers to data published in 2020.

Human rights have deteriorated sharply under President Bolsonaro

The latest findings from the Human Rights Measurement Initiative for Brazil include some positive economic and social rights scores, but also some strikingly poor results in civil and political rights.

Data were collected and calculated before the Covid-19 pandemic. In 2021, HRMI will produce its annual update to cover the 2020 period, and also specific data on how the pandemic has affected human rights in Brazil.

Some of the headlines from below:

- Freedom of speech plummets

- Human rights worse under Bolsonaro

- Indigenous people experience high rates of rights violations

- Racism drives human rights violations

- Progress stalling on rights to food, health, education, and work

- If Brazil were operating at best practice, an extra 660,000 primary school aged children could be enrolled in primary school, and an additional 3.2 million secondary school aged children could be enrolled in secondary school.

- If Brazil were operating at its full potential given its current resources, it could lift 20 million people out of absolute poverty.

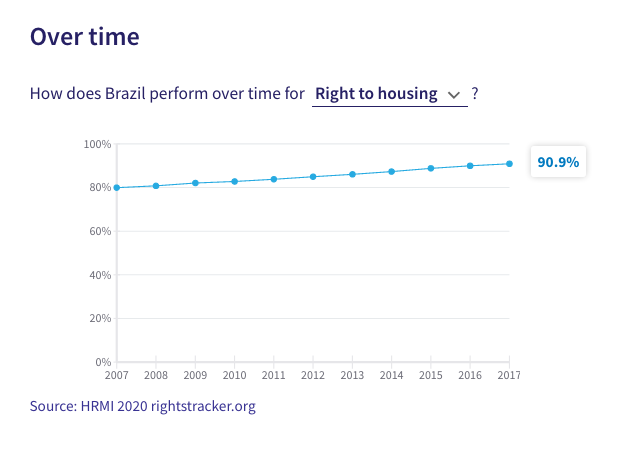

- Small gains in right to housing

- If Brazil used its resources effectively, an additional 24 million people could have access to basic sanitation and an extra 3.7 million people could have access to water on site.

Human rights in Brazil at a glance

The civil and political rights data, and the people at risk responses, were collected as the Covid-19 pandemic was beginning to sweep the world.

The economic and social rights data are based on figures from international databases and score every year 2007-2017.

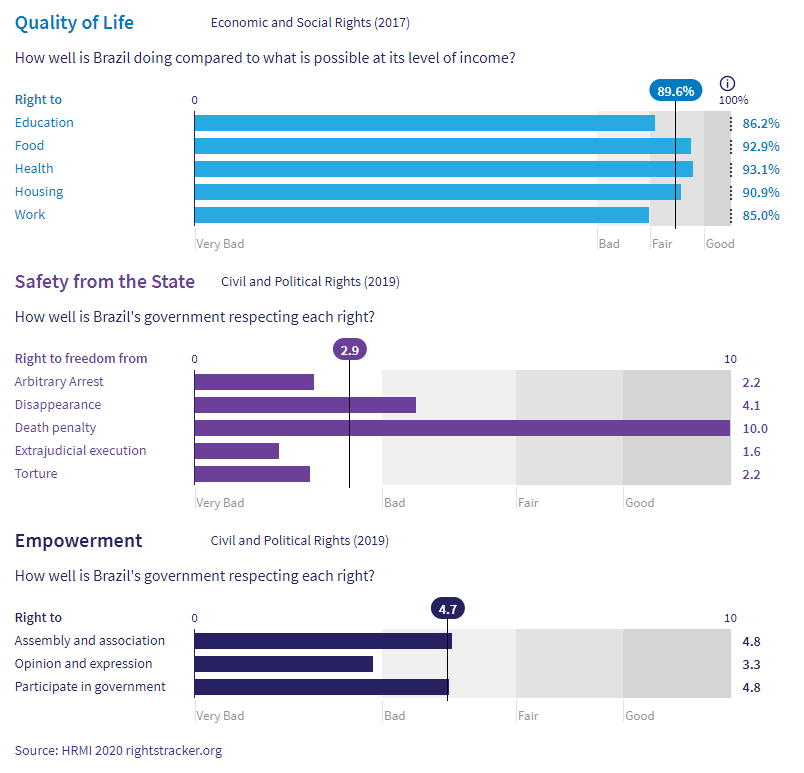

Safety from the State

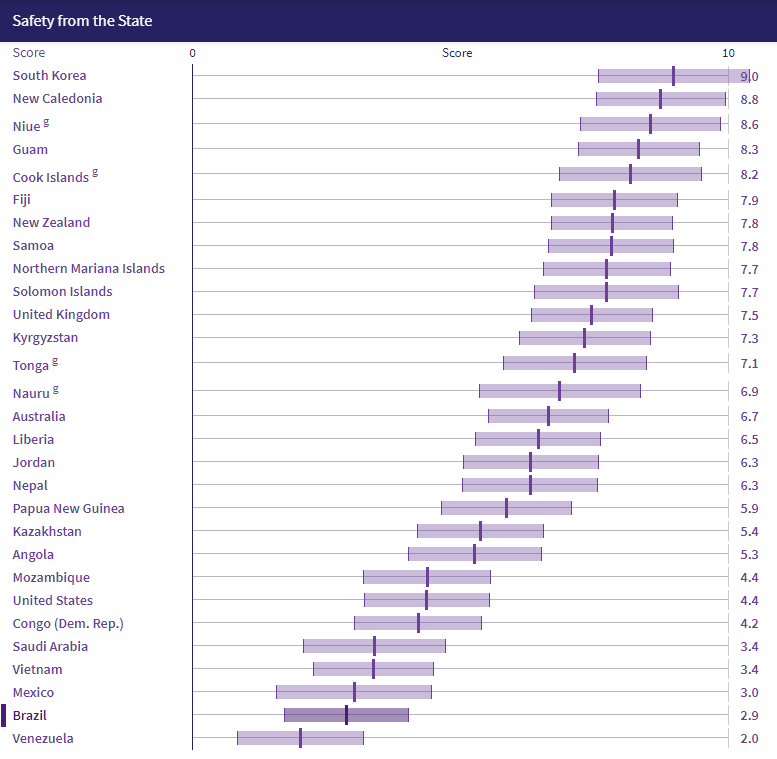

Brazil’s Safety from the State score of 2.9 falls in the very bad range, and suggests that many people are not safe from one or more of the following: arbitrary arrest, torture, disappearance, or extrajudicial killing.

For the civil and political rights we do not have data for enough countries in the Americas to do a regional comparison. However, compared to the other 28 countries in our sample, Brazil is performing worse than average on the right to be safe from the state.

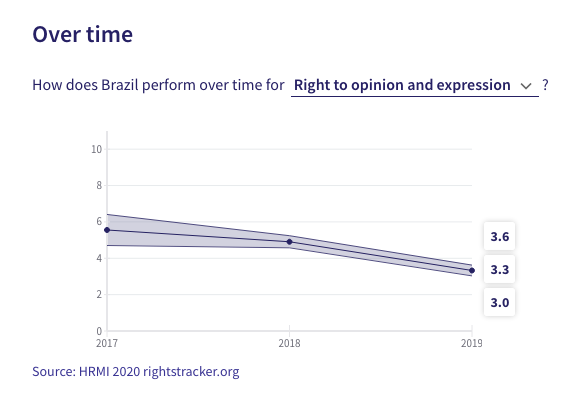

Freedom of speech plummets

People have been struggling more and more to speak out in Brazil, as the country’s scores for the right to opinion and expression have dropped sharply over the last two years. Expert respondents put Brazil’s score for this right at 5.6 out of 10 in the year 2017. By 2019, Brazil’s score had dropped to 3.3 out of 10, worse than most countries in our sample.

Human rights worse under Bolsonaro

There has been a sharp decline in Brazil’s scores for the right to opinion and expression and the right to freedom from arbitrary arrest after President Jair Bolsonaro came to power.

Human rights advocates, members of labour unions, journalists, black people, and indigenous people were identified as being particularly vulnerable to violations of these rights.

Indigenous people experience high rates of rights violations

Indigenous people in Brazil were identified as being at higher risk of rights violations for every human right we measure. In particular, indigenous people were at risk of violations of their:

- right to freedom from disappearance

- right to freedom from torture

- right to participate in government

- right to food

- right to education

- right to health.

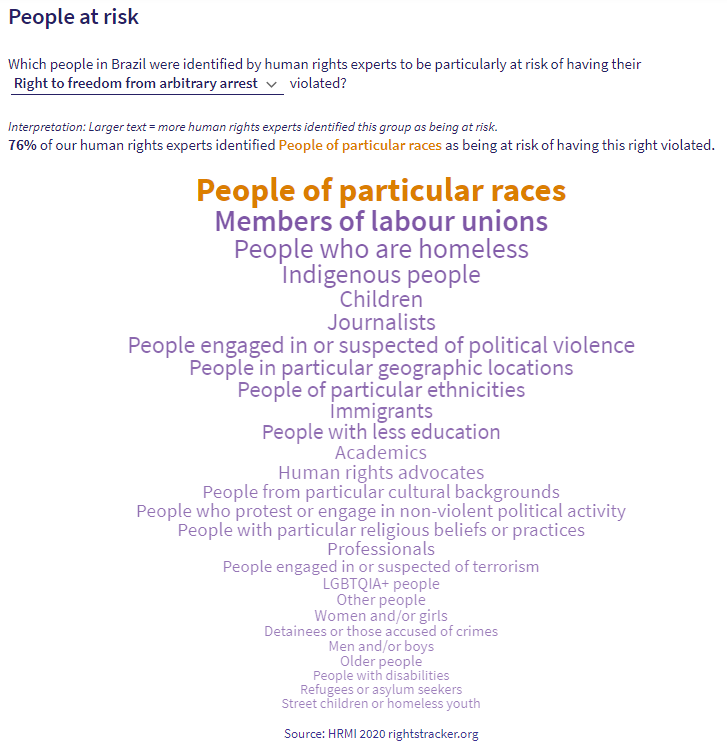

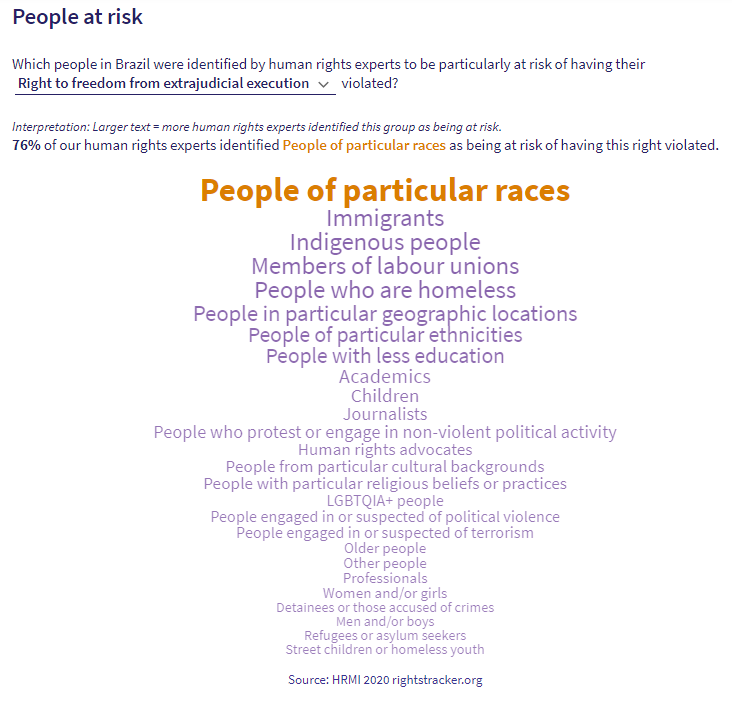

Racism drives human rights violations

Black people and indigenous people were identified as being at greater risk of a wide range of human rights violations in Brazil.

In relation to the justice system, 76% of respondents identified race as a factor in making people more vulnerable to arbitrary arrest and extrajudicial killing by government agents in 2019.

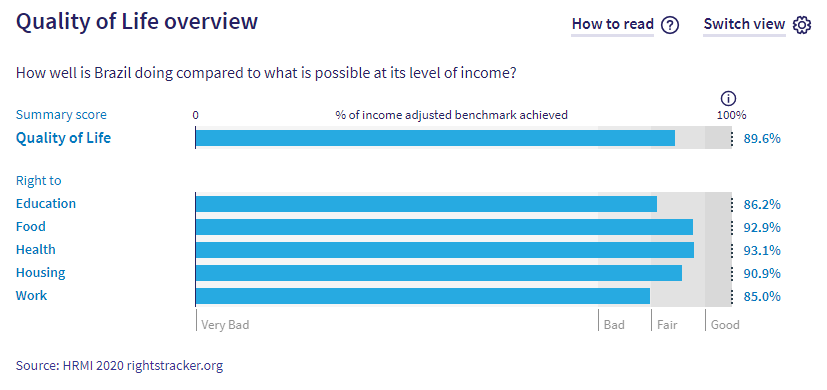

Progress stalling on rights to food, health, education, and work

Brazil scores 89.6% on Quality of Life when scored against the ‘Income adjusted’ benchmark. This score takes into account Brazil’s resources and how well it is using them to make sure its people’s Quality of Life rights are fulfilled.

This score tells us that Brazil is only doing 89.6% of what should be possible right now with the resources it has. Since anything less than 100% indicates that a country is not meeting its current duty under international human rights law, our assessment is that Brazil has some way to go to meet its immediate economic and social rights duty.

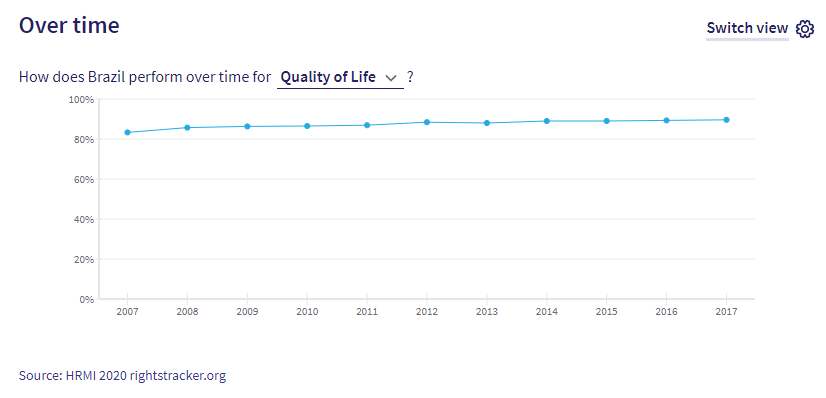

Brazil’s scores for the rights to food (92.9%), health (93.1%), education (86.2%), and work (85%) have increased over the the last 20 years, suggesting that over the last decade Brazil has got better at using its wealth to meet people’s basic rights. However, progress has stalled on these scores since 2014, suggesting that Brazil has not been making gains in the last few years in using its resources to meet Brazilians’ needs.

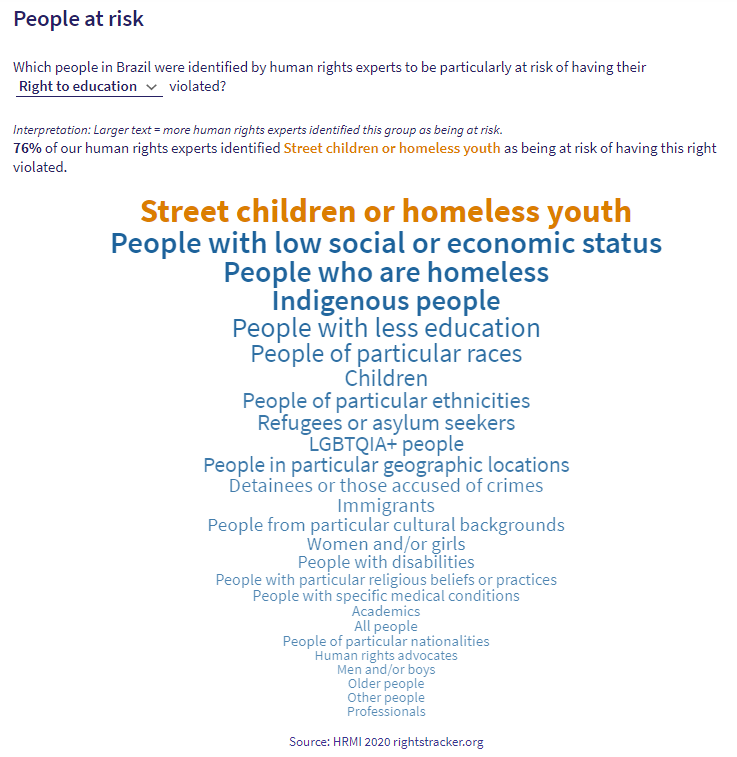

Right to Education

Brazil is doing 86.2% of what should be possible at its level of income on the right to education, which is relevant for SDG 4: Quality Education and SDG 1: No poverty.

76% of our human rights expert respondents identified street children and homeless youth as being at particular risk of having their right to education violated.

If Brazil were operating at best practice, an extra 660,000 primary school aged children could be enrolled in primary school, and an additional 3.2 million secondary school aged children could be enrolled in secondary school.

Right to Work

On the right to work, Brazil is doing 85.0% of what should be possible at its level of income. According to international law, everyone is entitled to the opportunity to gain a living by work that is freely chosen and ‘the right to the enjoyment of just and favourable conditions of work’. This includes ‘equal pay for equal work, the chance to earn a decent living for [ourselves] and [our] families, just and safe working conditions, and a reasonable limitation of working hours‘ (ICESCR, Articles 6 and 7).

When asked to provide more context about who was particularly unlikely to enjoy their right to work in 2019, our respondents mentioned all of the following, and more:

- People of low social or economic status, particularly homeless people

- People of certain races, including black people and Quilombolas

- Young people, particularly those with low education levels

- Immigrants

- Rural people and those living in peripheral areas

- LGBTQIA+ persons, especially transgender persons

If Brazil were operating at its full potential given its current resources, it could lift 20 million people out of absolute poverty.

Small gains in right to housing

Brazil has made small but steady gains in meeting the right to housing since 2007, with a moderate increase every year. This means that over the last decade Brazil has steadily increased from a score of 79.9% in 2007 to a score of 90.9% in 2017. While this score falls in the ‘fair’ range, if Brazil used its resources effectively, an additional 24 million people could have access to basic sanitation and an extra 3.7 million people could have access to water on site.

More information on human rights in Brazil

For more insights into trends, challenges, and people at risk of rights violations in Brazil, visit our Rights Tracker. All our data are freely available for your use.

Thanks for your interest in HRMI. To further explore our human rights data for Brazil, please visit our Rights Tracker, where you can find data by country or right.