Does promoting economic and social rights defeat or fuel economic growth?

Written by Elizabeth Kaletski & Susan Randolph

This working paper was initially published as a short article for the Loop. Listen to Elizabeth explain these findings in this YouTube video.

Abstract

The International Covenant on Economic Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) requires countries to devote maximum available resources to progressively realize the economic and social rights (ESR) outlined within the treaty. Additionally, increasing economic growth not only remains one of the most important policy goals for countries around the world but also provides the means for the future enhancement of economic and social rights. As a result, academics, policy makers, and businesses regularly question whether focusing on the commitments of human rights doctrine comes at the cost of decreased growth. To inform policy, it is therefore important to understand whether this tradeoff exists and whether there are specific rights that promote or hinder economic growth. We find that ESR and economic growth are mutually reinforcing, and prioritizing ESR may be the best path towards improvement on both growth and human rights. Further research should utilize HRMI’s data to discover the mechanisms which lead to improved performance.

ESR, ESG, and economic growth

The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) requires countries to devote their maximum available resources in order to progressively realize the rights enumerated therein. Although this formal commitment has often led to improvements in economic and social rights (ESR) over time, some policy makers are concerned that the focus on human rights comes at the cost of reduced economic growth.

In some countries – including the United States – this has evolved into political opposition to Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) frameworks which push the public and private sector to consider the impacts of their decision-making beyond short-term financial concerns. Some have argued that prioritizing issues other than the bottom line – such as the health and education of the workforce – reduces profit for companies and lowers overall GDP growth.

But the empirical evidence on these relationships remains inadequate. We utilize the Human Rights Measurement Initiative’s (HRMI) income adjusted quality of life index, also known as the SERF index, to show that not only are these concerns likely overblown, but ESR and economic growth tend to be mutually reinforcing. Further, prioritizing ESR may be the best path towards improvements on both growth and human rights.

Is there a conflict?

The language of the ICESCR, which requires using maximum available resources to progressively realize the rights enumerated, implies that ESR rather than economic growth should be the primary priority of state parties. And there may be reasons why steps taken to meet obligations of ESR fulfillment can conflict with those that might best support economic growth (and vice versa). For instance, technological innovation has been identified as essential for promoting growth. But if that occurs by concentrating government investment on higher education, it leaves fewer resources to expand broader access to education.

On the other hand, there exists evidence of a positive relationship between expanding access to education and economic growth. Policies that promote high quality education and access to health care connect to the fulfillment of the rights to education and health. They also have the potential to benefit business and the broader economy because an educated and healthy workforce is more productive. This relates directly to the social component of ESG – the least studied element of the framework – and its potential to fuel growth.

There are many potential theoretical connections between ESR and growth, and the specific policies and steps taken by businesses and governments to promote each vary widely across the globe. Here, rather than examining specific policies, we empirically investigate the relationship between country enjoyment of economic and social rights and their record of economic growth.

Economic and social rights measurement

The ICESCR enumerates the economic and social rights that all human beings are entitled to based on their inherent dignity. These include access to basic goods, services, and opportunities that are necessary to not only survive, but also reach their full potential. HRMI’s income adjusted ESR metrics, also known as the SERF index, focus on the rights to education, food, health, housing, and work.

The measures are developed using internationally comparable and publicly available data and cover 194 countries from 2000-2020 (though coverage varies depending on the right in question). The data include measures for the five individual rights outlined above, along with an overall quality of life index which combines the five rights into one indicator. We specifically use the income-adjusted version of these data, which are identical to the SERF data, and measure how individual countries are doing relative to what is feasible given their level of economic resources.

Transition patterns

We combine the ESR scores with data on per capita GDP annual growth rates from the World Development Indicators to examine patterns in country performance from 2010 to 2020. Based on the data, and the methodology developed by Ranis, Stewart, and Ramirez (2000), we separate countries into four categories along two dimensions – ESR fulfillment and economic growth performance.

Those that perform better than the median in the year concerned in terms of both rights fulfillment and economic growth are classified as virtuous – this is the best-case scenario. Those that perform worse than the median in the year concerned on both rights fulfillment and growth are subsequently classified as being in a vicious cycle. Those with a score above the median for ESR fulfillment but below the median for growth in the year concerned are ESR-lopsided and the reverse situation is considered growth-lopsided. We do a separate analysis for each of the five distinct rights in the HRMI data along with the overall quality of life index.

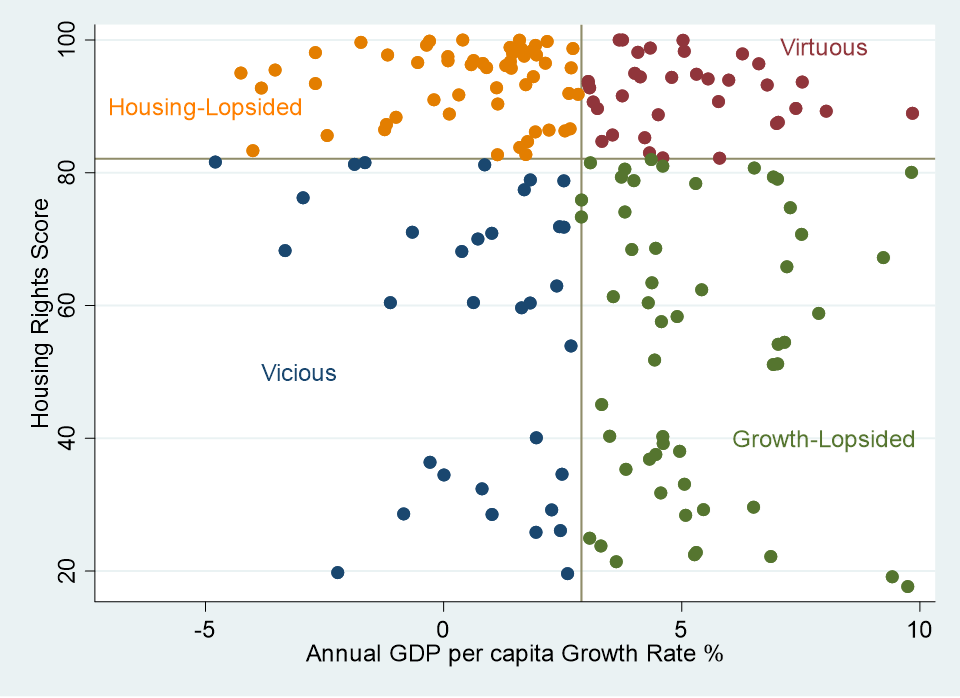

Based on this categorization, Figure 1 shows the starting position of each country (represented by individual points) in 2010 using the right to housing score as an example. The horizontal and vertical lines indicate the median housing score and annual GDP per capita growth rate, respectively.

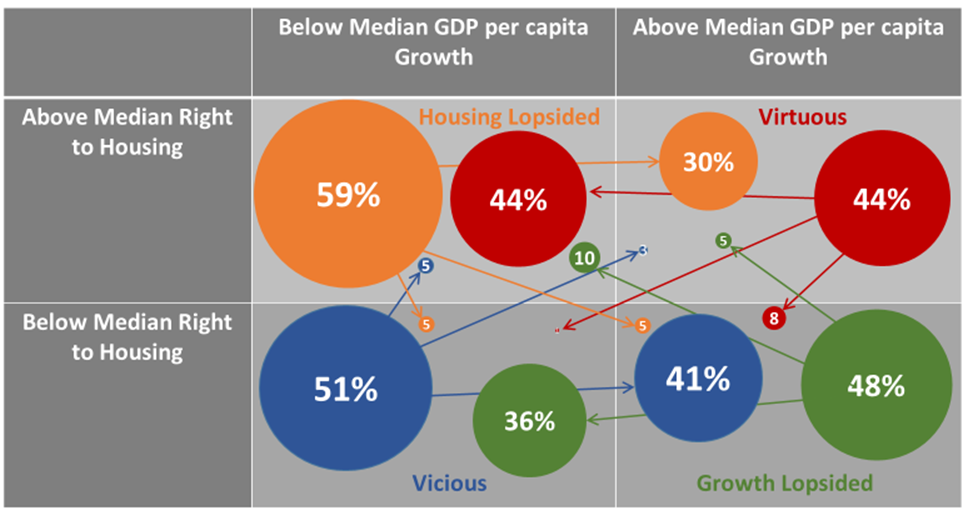

Once we identify the starting position for each country in 2010, we track where they end up ten years later in 2020. Figure 2 shows these transitions based on the right to housing data. The large blue circle in the bottom left quadrant indicates that 51% of countries that begin in the vicious category in 2010 remain there in 2020. Similarly, 44% of countries that begin the top right virtuous quadrant remain there.

These results indicate that a high percentage of countries that begin in either the vicious or virtuous category are likely to stay there. This implies that once a country falls into the vicious category it is difficult to escape, but if it can reach the virtuous category the benefits are likely to be enduring.

This also leads to conclusions about countries that do end up transitioning over the decade. The large orange circle in the top left quadrant indicates that 59% of countries that began in the housing-lopsided category in 2010 remain there in 2020. But the arrows leading to other quadrants show the percentage of countries transitioning to different categories over the period – 5% move to the vicious category, 5% to the growth-lopsided category, and 30% to the virtuous category. Similarly, the green bubble in the bottom right quadrant reveals that 48% of countries that begin in the growth-lopsided category stay there, but 5% transition to virtuous, 10% to housing-lopsided, and 36% to the vicious category.

The data then indicate that countries that begin in the ESR-lopsided category are either likely to remain there or transition to the virtuous category. Few countries that began in this category transitioned to either the growth-lopsided or vicious category. Thus, countries that do a better job of fulfilling their commitments under the ICESCR tend to enjoy a growth benefit in the subsequent decade.

In contrast, countries that began in the growth-lopsided category either remained there or transitioned to the vicious category. Few countries that began in this category transitioned to either ESR-lopsided or virtuous categories. These results indicate that in the absence of ESR fulfillment, maintaining rapid economic growth is difficult. It is important to note that although the numbers presented here are specific to the right to housing data, these patterns are robust across all the individual rights measures and for the overall quality of life index.

Where does that leave us?

Taken together, the results show that there does not appear to be a conflict between fulfilling ESR and economic growth. Rather, ESR fulfillment and growth are mutually reinforcing. Given the current discussions in popular media outlets around ESG and the broader concerns about prioritizing human rights over growth, these results provide evidence that those concerns may be overblown.

Further, the best path towards the optimal category of virtuous – where a country performs well on both ESR and economic growth – occurs by prioritizing ESR fulfillment over economic growth. Questions remain as to the mechanisms through which this occurs, and further research should seek to identify policy prescriptions that lead to this positive outcome.

References

Fukuda-Parr, Sakiko, Terra Lawson-Remer and Susan Randolph. 2015. Fulfilling Social and Economic Rights. Oxford University Press.

Human Rights Measurement Initiative (HRMI). 2022. « HRMI Human Rights Dataset. » https://humanrightsmeasurement.org/. Version 2021.6.6.

Ranis, Gustav, Stewart, Frances, & Ramirez, Alejandro. 2000. Economic Growth and Human Development. World Development, 28(2), 197-219.

World Bank. 2023. World Development Indicators. https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators.

Elizabeth Kaletski explains the research

Watch Elizabeth explain this research during HRMI’s 2023 Economic and Social Rights webinar.