Press Freedom in Australia

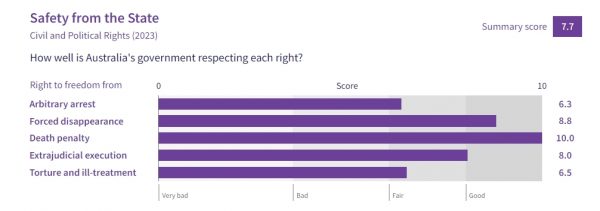

Australia presents itself as a land of individual prosperity, with an open democracy, high education rate, and free healthcare. Indeed, this self-perception is celebrated in Australia’s national anthem, Advance Australia Fair. However, despite these relative advantages, press freedom and protections for whistleblowers are not secure. According to the Human Rights Measurement Initiative (HRMI), Australia scored an unimpressive 6.3/10 for freedom from arbitrary arrest and 6.5/10 for freedom of opinion and expression in 2023. These scores suggest that a substantial number of people are not safe from the state, or able to enjoy rights of empowerment—i.e., civil and political rights. An examination of recent events pertaining to press freedom and whistleblowing can provide insights into these relatively low scores.

Since 2001, Australia’s Parliament has passed around 75 pieces of counter-terrorism legislation that have cumulatively contributed to the undermining of press freedom. This issue came to the fore in 2019. Annika Smethurst had published several articles revealing top secret memos outlining a planned expansion of powers of intelligence agencies to covertly access Australian citizen records without a warrant. Similarly, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) published “The Afghan Files” revealing that the Australian defence community had covered up war crimes committed by elite Australian soldiers. Smethurst’s home and ABC headquarters were raided by the Australian Federal Police (AFP) as part of their investigations into unauthorised disclosures of classified material.

Public outcry and legal challenges ensued. A Senate inquiry into law enforcement, intelligence powers and press freedom were launched. No charges were ultimately brought against journalists. However, the Senate inquiry found that cases like these had created a “chilling effect” on journalists reporting on matters of national interest due to fears of prosecution. Whistleblowers similarly reported experiencing “incredible anxiety about having any trace of conversation with journalists.” Such testimony highlights the prohibitive impact of these policies. For whistleblowers, however, their fears have materialised—they are starting to be imprisoned.

David McBride was identified as the individual who leaked the documents that became “The Afghan Files.” His legal team’s defence of public interest was rejected by the trial judge. McBride consequently pleaded guilty and was sentenced to six years in prison in 2024. In a similar but unrelated case, “Witness K” was given a suspended sentence in 2022 for revealing that Australia had secretly bugged East Timor’s cabinet during oil and gas negotiations shortly after its independence from Indonesia in the early 2000s. Their rights to freedom from arbitrary arrest and opinion and expression have been violated.

Whistleblowers are also being prosecuted for cases unrelated to national security. Richard Boyle is facing potential jail time for blowing the whistle on unethical debt collection practices by the Australian Tax office. This prosecution is currently ongoing despite several independent inquiries vindicating Boyle’s assertions, creating a catch-22 situation. The Human Rights Law Centre mentions that Boyle “faces prosecution—not for his public whistleblowing, but for his actions gathering evidence”. Richard Boyle is presently being support by the HRLC, whose purpose is to engage in “fearless human rights action for a fairer future for all“. HRMI data support the HLCR in this endeavour.

HRMI measures human rights as defined by the United Nations. Protections for journalists and whistleblowers are essential for the public’s right to know and are articulated in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). Australia was an original signatory to UDHR in 1948, and ratified ICCPR in 1980. However, neither has been adopted into domestic law. Australia consequently stands out as one of the few Western democracies that neither legally recognises nor protects press freedom. This has enabled the Commonwealth Parliament to enact national security laws without appropriate consideration to journalists and whistleblowers.

Combined with HRMI’s scores, the examples presented in this article reveal that there is a serious lack of respect for these rights in Australia today. Australia requires urgent legislative reform to align its laws with international commitments. Human rights data can play an active role in clearly defining this discrepancy—one of the primary rationales for HRMI. By quantitatively demonstrating deficiencies in certain rights, what may be qualitatively perceived can be empirically validated. When strategically leveraged, this data can shift public opinion and, consequently, influence public policy. However, for this to happen, the data must first be collected and broadcast.

HRMI publishes data on hundreds of countries worldwide, using robust and peer-reviewed methodologies. At the core of this methodology is expert input from people on the ground, many of whom live in authoritarian regimes that have significantly lower scores in terms freedom from arbitrary arrest and opinion and expression compared to Australia. Like Australian whistleblowers, their lives and livelihoods may be at risk when reporting human rights infringements to HRMI. HRMI consequently ensures all data is anonymised and securely stored. Their aspirations for a more democratic future help turn fantasy into reality. Thus, HRMI’s data is underpinned by courageous individuals, while Australia’s liberties are strengthened by indomitable journalism.